Opinion Sourav Ganguly turns 50: The Dada myth does not get old

Bengalis are congenital social scientists and cricket lovers. The two streaks blended to make Sourav a veritable signifier of all that ails us and all that keeps us afloat

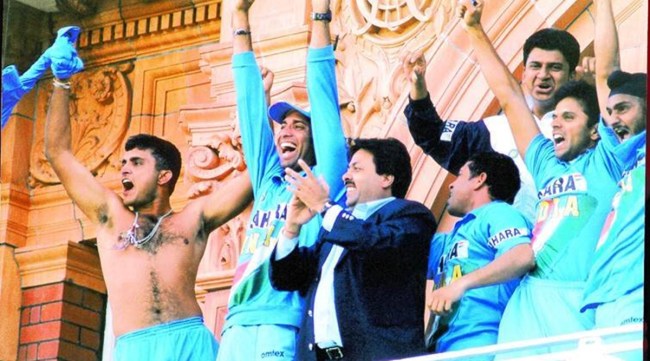

Sourav Ganguly celebrates India’s victory against England at Lord’s. (Express Archive)

Sourav Ganguly celebrates India’s victory against England at Lord’s. (Express Archive) Sourav Ganguly turned 50 on July 8. But the person who was baptised as “Dada” that the country loves to adore and look up to was born only in 1996 at Lords, when this debutant smashed the Englishmen for a swashbuckling century, dauntless, aggressive and artistic. As a longstanding captain, Dada became the symbol of the same traits – zeal and arrogance (not particularly Bengali traits) blended with cool analysis. Long before his retirement, as he went on achieving one feat after another, he became the stuff mythologies are made of. The episode of Sourav taking off his t-shirt at Lord’s balcony in 2002, waving and wheeling it bare-bodied, to me is a perfect metonymic expression of postcolonial brashness and vigour. A lot is written into it that stretches beyond the cricket field.

Strangely, I didn’t like Sourav when I first saw him back in 1991. It was a warm-up match in uncricketing, officious Canberra. He fielded in the deep, allowing me to see him at a close distance. His body language wasn’t encouraging. As a matter of fact, he seemed a shade lazy, if not a bit spoilt. I forgot him and nobody reminded me.

A good five years went by. Then, one day, as I was having tea with a Bangladeshi friend, his son popped in and announced with gusto: “Do you know who’s the best Indian batsman today? It’s none else than our Sourav Ganguly.” I chose to read his pronouncement as more of an expression of cross-border Bengali nationalism, not always forthcoming and seldom reciprocated. One didn’t get to read much about him, such is the Australian media’s brand of cosmopolitanism. His name, however, kept coming back in the cosy weekend Bengali gatherings.

At last came the chance to see him in action again. India was visiting Australia and I got myself a ticket for the match at Gabba in Brisbane. Sourav’s innings did not last long, but long enough for him to lob the ball beyond the rope a few times. On one occasion, so high and fierce it went that I wondered whether the cherry actually reached my balcony, a few hundred meters away from the stadium. But what was more remarkable was the change in his persona: No more that teen-age brat I thought I saw, but a confident young man full of application and with a healthy dose of cricketing arrogance.

I finally returned to Calcutta in 1998. Sourav was all over. The city guarded him zealously, always proud of its new possession, always worried, always offering corrections. Each one of us became his alter-ego. Once his dilly-dallying to leave the crease caused Sachin’s dismissal. This had happened before as well. A colleague in the office library promptly explained the gesture as Bengal’s undying feudal hangover, reminding me of the proverbial peasant who would rather starve than give away an inch of his land. By all indications, Bengalis are congenital social scientists and also cricket lovers. The two streaks blended to make Sourav a veritable signifier of all that ails us and all that keeps us afloat.

I suspect the downturn began after the history-making win over Australia in 2004. Sourav got used to getting himself out cheaply, committing almost-suicide each time, and also making himself available for fights with the ICC. But the drama had to wait till the Emperor Down Under took the reigns and after the coronation decided to teach this local prince a lesson or two. The rest is mucky and, now, history. As the guy faltered even more, all that was needed was a mantle of joyous neutrality to facilitate the exit.

Sourav’s dismissal was on the platter for the media to froth and fret about. The cricket-loving then chief minister of Bengal consoled the hero, leaving his fast-loving political bete noire to read with apprehension the pally gestures. For the average Calcuttan, the event plainly signaled another great betrayal to Bengal. There was nothing much to talk about, save lingering over new episodes and new players of this unrolling epic. The city turned away from its prime obsession – cricket.

The dimly lit streets looked more solemn. No more were those clusters outside show windows of shops telecasting a live match. We tried to cope with our new emptiness, denying all the time that it had anything to do with Sourav being a Bengali. The ramifications went far beyond Bengal. Actually, the event occasioned a nation-wide gloomy festival that thrived in both elaborating itself and also announcing its redundancy. On one of those hapless, hopeless mornings, as I was rushing towards my room at work, the receptionist looked at me and asked despondently: “What do you think should be our strategy now?” I was taken aback. I had seen him poring over the sports pages of different vernacular dailies, but couldn’t remember him talking to me beyond the mere functional. I realised the depths of his frustration which was not his own alone. Thanks to Sourav, we all became, in a way, collective figures.

In retrospect, what seems most curious in the whole phenomenon is that once the much prayed for, much contested return actually materialised, it seemed nothing strange anymore, almost inevitable. The trying past of long 15 months disappeared like thin flakes of snow and everything was business as usual. His healthy average in the World Cup and sustained high scores including a century in the very first Test after exile, seemed so natural. However, his flawless 239 in 2007 at Bangalore was of a different genre. It was simply sublime.

In his triumphant return, he became the eternal symbol of sheer resilience. I am inclined to look not so much at past injuries (real even if they were) but how it is always possible to work on the self and make a rightful claim to lost honour. The ball that kissed the willow to travel skyward and fall from the nearby tree may or may not be the forbidden apple of Indian cricket. But one thing is for sure: Sourav has secured a permanent place in the country’s annals, not merely of cricket. No wonder the country never ceases to expect more from the Dada and no wonder he cannot but excel in every responsibility he is entrusted with.

The writer is a former professor of Cultural Studies at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta (CSSSC)