Opinion Remembering Ranajit Guha: He helped us understand the pre-colonial indigenous roots of Indian democracy

Guha helped establish the Subaltern Studies school of historiography, and shaped the emergence of postcolonial scholarship and non-Eurocentric global history

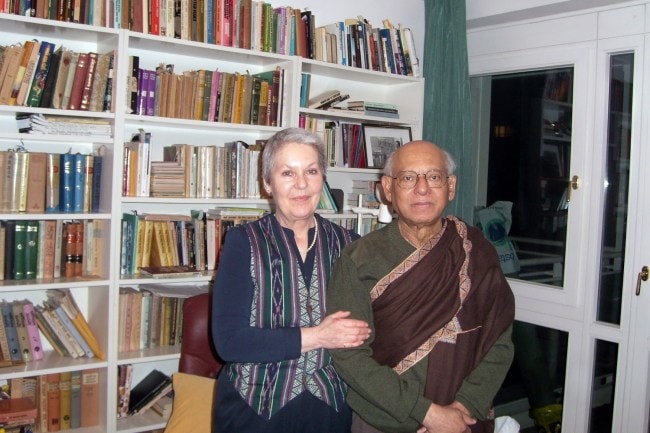

Ranajit Guha with his wife Mechthild in 2008. (Photo: Nonica Datta for Permanent Black)

Ranajit Guha with his wife Mechthild in 2008. (Photo: Nonica Datta for Permanent Black) Ranajit Guha (1923-2023) was among the greatest historians and political thinkers of 20th-century India. He helped establish the Subaltern Studies school of historiography and thus shaped the emergence of post-colonial scholarship and non-Eurocentric global history. To appreciate his genius, one must see him as a luminary of the age of decolonisation.

Like many other anti-colonial cosmopolitans of 20th-century Asia and Africa, he took inspiration from the German philosopher G W F Hegel. When I first met him in his home at Purkersdorf, a village on the outskirts of Vienna, in 2011, he mentioned how he had reworked Hegel’s figure of the bondsman/slave, whose emancipatory struggle against the lord/master provides the dynamic for the progress of world history, into the figure of the subaltern. Karl Marx equally inspired Guha to think about class conflict and revolution. As a socialist activist, Guha travelled across India, Europe, and West Asia.

Inspired by anti-colonial struggles in India and elsewhere — including the Communist Revolution in China and the Algerian War of Independence — Guha also swerved away from Hegel and Marx. For Hegel, state bureaucracy constituted a “universal class” which was the repository of modern Reason. Marx had applied this model of universal class to conceptualise the industrial working classes as the vanguard of socialist revolution who would overthrow capitalism and the rule of the bourgeoisie. Such a model was of little relevance to Asian and African societies where peasants constituted the vast majority and led resistance against European empires.

European-Marxian progressivism became a legitimating tool for the Soviet Union and other Soviet-allied states, including Nehruvian India, to carry out reforms that destroyed agrarian communities. Disenchanted by Soviet-style communism, Guha ultimately left the Communist Party in 1956, protesting against the Soviet invasion of Hungary. He found inspiration in Naxalite agrarian protests which erupted across 1960s-70s India. In his books A Rule of Property for Bengal (1963) and Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India (1983), Guha uncovered how the British colonial state worked with Indian elites to subjugate Indian peasants. He realised that precolonial-origin community structures and religious beliefs centrally shaped peasant rebellion against these oppressive elites. His manifesto essay “On Some Aspects of the Historiography of Colonial India”, that opened the first volume (1982) of the Subaltern Studies series, argued that the politics of the people/subalterns constituted “an autonomous domain”. “It was traditional only insofar as its roots could be traced back to pre-colonial times, but it was by no means archaic in the sense of being outmoded.”

Guha’s painstaking research helps us understand these pre-colonial indigenous roots of Indian democracy. We appreciate how modern Indian democratic politics owes its lineages as much, if not far more, to oppressed caste and tribal/Adivasi heroes, as to Western-educated elite statesmen. Guha knew that for Indian and global democracy to be strengthened, inspiration would have to come from the subaltern multitudes, rather than from the ideas of Locke or Mill, from the directives of Washington or Moscow. Elementary Aspects concluded that “all mass struggles will tend inevitably to model themselves on the unfinished projects of Titu, Kanhu, Birsa and Meghar Singh”.

To understand this revolutionary heritage, Guha delved in the last decades of his life into Indian philosophy and literature, mostly writing in Bengali. Guha presented Sita, Shakuntala, Draupadi, and Antigone as comparable rebellious women who resisted the violent male state. In the Stri Parva (Book of Women) of the Mahabharata, Guha discovered abiding female indictments of war.

When I last met him at Purkersdorf, in 2019, I was struck by Guha’s library shelves. Marx jostled close to the Mahabharata, pre-colonial Bengali mangalakavyas stood by Hegel and Heidegger. This cosmopolitanism was typical of the age of decolonisation — thinking across continents to create a democratic world that would be simultaneously indigenous and ecumenical. Guha exuded an Olympian warmth that would remind any Indian of their grandparents. As we discovered during our conversation at Purkersdorf, Guha’s paternal grandmother Abala and my maternal grandmother Sushama came from the same family, the Basu Raychaudhuris of Ulpur (now in Bangladesh). My grandmother became a socialist freedom fighter and spent time in colonial prison during the Quit India Movement; Guha’s years as a militant leftist helped him become a philosopher against power.

In mourning Guha, we mourn the passing of a generation, of an age. Yet, that age, of heroic anti-colonialism, remains of abiding relevance. In our era of climate crisis and fatal race/class inequalities, we see heterogeneous coalitions of subaltern movements arising — we find emancipatory hope in Dalit-Bahujan and Adivasi movements, in global Indigenous environmentalisms, in Black communities, in feminist strikes. We have not been fully decolonised — colonially-moulded structures of political and economic domination continue to oppress the vast multitudes across the world today. Hence, anti-colonial heroes, subaltern heroes, inspire our present struggles to create multi-species democracies, as my recent book Subaltern Studies 2.0 argues. When we memorialise these struggles, we shall also remember Guha, who was one of their greatest bards.

Banerjee is lecturer in Modern History, University of St Andrews, Scotland, the United Kingdom