Opinion The night Rajiv Gandhi was killed: A journalist remembers

‘You must be joking’ was my first reaction

I tuned in to the bulletin and heard the BBC correspondent (who was obviously not at the spot) state, “The bombs were apparently placed in flower pots at the venue and riots have broken out across Madras.”

I tuned in to the bulletin and heard the BBC correspondent (who was obviously not at the spot) state, “The bombs were apparently placed in flower pots at the venue and riots have broken out across Madras.” The recently released OTT series on the Rajiv Gandhi assassination and how the culprits were nabbed, The Hunt — The Rajiv Gandhi Assassination Case (Sony LIV), brought back haunting memories of that traumatic night. At the time, I was working with the Indian Express in Madras (now Chennai) in the sports department.

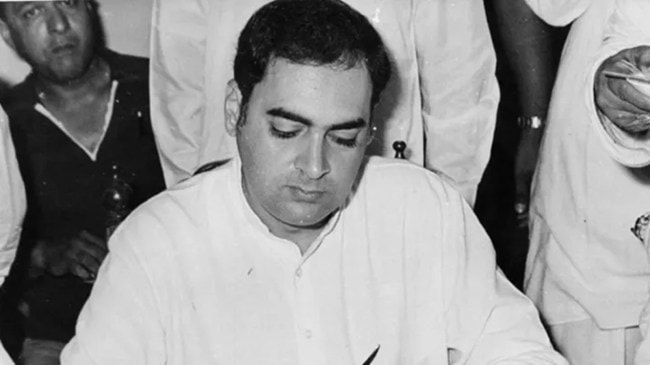

The national election was in full swing with former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi trying to make a comeback and defeat his former colleague-turned-bête noir, V P Singh. Rajiv Gandhi had served as Prime Minister following the assassination of his mother, Indira Gandhi, before the Bofors arms scandal saw his government fall in 1989. He had then pulled the rug from under the short-lived Chandra Shekhar government, necessitating snap elections.

Rajiv Gandhi was visiting Sriperumbudur, 40 km southwest of Madras, for a routine election rally. The town was familiar to me as it was the venue for the annual races conducted by the Madras Motor Sports Club, which I had reported on.

I was living in the suburb of Adyar with my parents and was alerted by them to a phone call from the sports department at 10.45 pm. It was a Tuesday, May 21, and it was my off day. Such calls at night from the department were not an unusual occurrence, and I took it, thinking it was a routine one.

But the voice on the other side was grim. It was my colleague asking me if I had been listening to the BBC World Service. It was well known in the office that I was a regular listener on my transistor to their sports and news bulletins. I asked him why, and he replied: “We have heard Rajiv Gandhi has been assassinated. Please listen to the 11 pm bulletin and confirm.” My first reaction was to laugh and say, “You must be joking!” But he replied, “Would I joke about something like this?”

I tuned in to the bulletin and heard the BBC correspondent (who was obviously not at the spot) state, “The bombs were apparently placed in flower pots at the venue and riots have broken out across Madras.” Neither turned out to be true, though there were sporadic bouts of violence in the city. Of course, at that time of night, rumours were flying thick and fast.

Ironically, when his mother was assassinated in October 1984 in the capital, Rajiv was out of New Delhi and told reporters he had confirmed the news via the BBC.

The news was conveyed to the office, and the dak (early morning) edition was held back till our reporter and photographer returned from Sriperumbudur. They did so in a state of panic following the horrific scenes which they had just witnessed. Both hitched a ride in cars of local Congress leaders with chaos, panic and trauma all round at the mass killings. Remember, there were no mobile phones back then.

My mother broke down and wept on hearing the news. A childhood friend of Mrs Gandhi’s, I gently asked her why she did not react the same way when Mrs Gandhi had been murdered seven years earlier. Mother’s words haunt me to this day: “Because he (Rajiv) is so young.”

It was a typically stifling hot and humid May night in Madras. In a daze, I stumbled out of the house, telling my parents I would be back soon. The streets were deserted, the only sound being that of stray dogs barking. A neighbour of mine sitting in his garden had heard the news and asked me, “Is it the LTTE?” No one knew the answer at the time, though that was the immediate thought of everyone that horrific night.

It must have been a good two hours before I returned home that horrible night. To this day, I have no idea where I had wandered off and how much time had elapsed. But my parents were panicking, concerned I had been caught up in riots.

Our photographer’s pictures were splashed across the front and inside pages, gory though they were. The only other English daily in Madras at the time had sent a reporter, but not a photographer and had to buy them late at night from a local photographer.

A couple of days later, I requested my reporter and photographer colleagues to sign the front page as my brother and I had a hobby of preserving newspapers with historic headlines, some with autographs. The reporter agreed reluctantly. But the photographer did not. I well understood. After all, he had not been far from the stage when the suicide bomber set off her bomb and the trauma was obviously still raw.

The writer is a senior journalist and author based in New Delhi. He was with Indian Express from 1982 to 1991