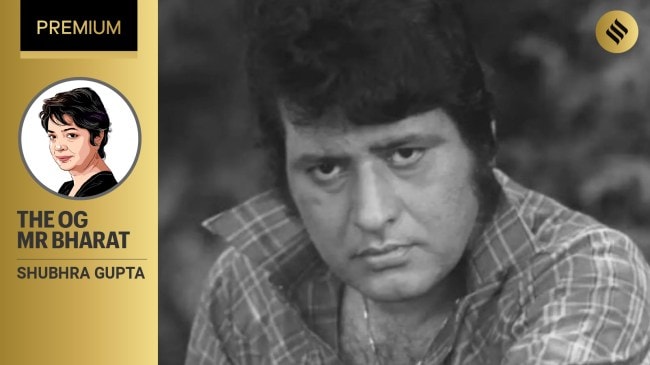

Opinion Manoj Kumar was the original Mr Bharat

His brand of nationalism belonged to a softer, gentler era.

Manoj Kumar’s early successes were some of the most interesting mystery thrillers made in Hindi cinema.

Manoj Kumar’s early successes were some of the most interesting mystery thrillers made in Hindi cinema. “Bharat ka rehne wala hoon, Bharat ki baat sunata hoon”.

It’s surprising that this song, from the 1970 film Purab aur Paschim, has been nearly forgotten: If he was still working, Manoj Kumar would have been the poster-boy for patriotism, even if his brand of nationalism belonged to a softer, gentler era.

Decades before the current iteration of Bharat-that-is-India became a slogan, a Hindi movie star had made it his moniker: More than his own name, Manoj Kumar became known as Mr Bharat, his identity cemented by a super-hit clutch of patriotic films.

Harikrishan Goswami, whose family, like so many of the earlier stars in Hindi cinema, came over to a newly-born India after Partition, changed his name to Manoj, a character in his idol Dilip Kumar’s film. He came into the movies towards the end of the ’50s, when the iconic trio of Dilip Kumar-Dev Anand- Raj Kapoor was ruling, and like several of his contemporaries, notably Rajendra Kumar and Raaj Kumar, struggled to find a foothold in Bombay’s film industry.

Movie stars in those days were even more prisoners of their image. Dilip Kumar’s ability to do droll comedy was forgotten by those who dubbed him “tragedy king”. Rajendra Kumar, who did a string of films in which his clean-cut characters sacrificed the love of their life, found maximum success following Dilip Kumar’s tragic-hero footsteps. “Jaani” Raaj Kumar swung along the path of cool modernity forged by Dev Anand, getting his own signature moves in place, the more mannered the better.

Manoj Kumar’s early successes (Woh Kaun Thi, 1964; Gumnaam, 1965) were some of the most interesting mystery thrillers made in Hindi cinema, but he soon realised that his patriotic roles were the ones that would give him both box-office success as well as lasting recognition. Once he had done films like Shaheed (1965), and Upkar (1967), there was no drifting off to other genres — three years later came Purab aur Paschim, which became the template for the “good desi, bad pardesi” trope.

It would be tempting to call Upkar, Manoj Kumar’s directorial debut set against the backdrop of the 1965 Indo-Pakistan war — made at the behest of then Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri — a propaganda film. But that would be a reductive reading. It underlined Shastri’s focus on celebrating the “jawan” and the “kisan”, the two pillars he saw as the inheritors and creators of ’60s India, whose primary agrarian nature hadn’t been taken over by industrialisation.

Manoj Kumar’s character, named Bharat, plays the good man who wants to preserve his land at all costs; his evil brother Puran, played by popular villain Prem Chopra, wants to sell it for profit. Fittingly, the enemy, both in terms of the neighbouring country, as well as the citified brother, are vanquished. The jawan and the kisan are left to till their fields, with Bharat singing “mere desh ki dharti sona ugley, ugley heere moti”, a song that still evokes “rashtra-bhakti”. The image of Manoj Kumar, with the “hal” on his shoulder, harks back to Nargis doing the same in the 1957 Mother India, almost a precursor in its overarching themes of good-and-evil, the ongoing struggles of those who lived in India’s villages, and the conflation of the main character with the country.

It was with Purab aur Paschim that Manoj Kumar ratcheted the Bharat-is-the-greatest principle to its zenith, with the lyrics “jab zero diya mere Bharat ne, duniya ko ginti tab aayi”, extolling the virtues of sabhyata and sanskriti. It also gave Hindi cinema its everlasting template of the “bad girl who smoked and drank because of pernicious Western influence”, in Saira Banu’s leading lady, whom our Bharat tames and changes into a non-smoking, non-drinking “adarsh Bharatiya nari”.

By the time he made the 1974 blockbuster, Roti Kapada aur Makaan, a sharp, ironic counterpoint to then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s mid-’60s electioneering slogan, it was clear that the time had come to interrogate the unthinking patriotism of the earlier era. The 1981 Kranti, a historical drama top-lining both his idol Dilip Kumar and the theme of patriotism, was his last successful outing. What would Manoj Kumar, who had joined the ruling party after his starry days were behind him, have made of the current prevalence of hyper-nationalism? What would the original Mr Bharat have to say of this edition of India-that-is-Bharat? You wonder.

shubhra.gupta@expressindia.com