Opinion Can Mandal and Kamandal go together? The logic behind caste census announcement

Contrary to the conventional political wisdom, politics of caste and politics of Hindutva, far from being necessarily antithetical, can blend under appropriate circumstances

To frame the caste census as divisive misunderstands both the purpose of democracy and the nature of caste. Division is not caused by recognition; it is caused by systemic invisibility.

To frame the caste census as divisive misunderstands both the purpose of democracy and the nature of caste. Division is not caused by recognition; it is caused by systemic invisibility. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led union government’s decision to undertake caste enumeration during the upcoming Census exercise seems to be counterintuitive. The opposition parties, mainly the Congress, consider the politics of caste as a ready-made antidote to Hindutva. The caste census (as it is commonly called) is perceived to be the right recipe that will produce this antidote by providing a powerful impetus to OBC (Other Backward Classes) mobilisation for a much larger share of quota in public employment and education.

However, contrary to the conventional wisdom, the politics of caste and politics of Hindutva, far from being necessarily antithetical, can blend under appropriate circumstances. While political articulation of caste identity is typically seen as an impediment to Hindutva, several ethnographically grounded accounts have brought to light the rising phenomenon of “vernacular Hindutva”, which comes up with different strategies in different regions, emphasising the Hindu cultural roots of marginalised castes and tribes. These range from the cultural reconstruction of local Dalit heroes as Hindu avatars and crusaders against medieval Muslim rulers in northern India to forging a convergence between indigenous culture and the Hindu tradition in the tribal Northeast to the invocation of Dalit groups’ collective memory of Partition-induced religious persecution in West Bengal. Further, post the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations, the BJP has slowly but silently adjusted to Mandalisation by adopting former BJP General Secretary K N Govindacharya’s formula of “social engineering”. This enabled the rise of an array of OBC leaders like Kalyan Singh, Uma Bharati, Narendra Modi, Shivraj Singh Chouhan and Sushil Modi the party.

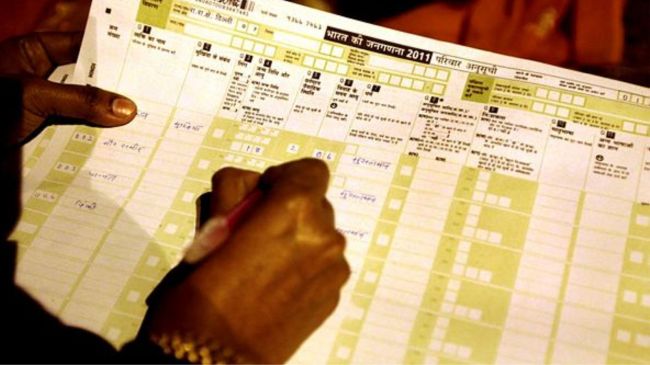

While the caste census apparently contradicts the Hindutva common sense, conveyed by slogans such as “batenge to katenge”, the logistical and methodological complexities involved in the entire exercise could offer enough manoeuvring space to Hindutva politics. Caste is not akin to gender or age, about which information can be collected with relative ease and certainty. The fluidity of caste identity is manifested by the multiplicity of caste labels, their context-specific usage and the lack of clarity about the defining features of caste as a social formation. The Socio-economic Caste Census, 2011, threw up 46 lakh caste names, many of which were either overlapping or unidentifiable with caste identity. This ruled out the possibility of classifying and categorising them.

Hence, the caste census is not a passive exercise of data collection. It involves reordering our social world through the creation of categories for making sense of an enormous amount of disparate data. The colonial census had played a pivotal role in converting the previously fuzzy caste and religious identities into the ossified enumerated identities. Therefore, the proposed Census will not only gather social facts about caste but will also actively intervene in the social process of making people discover their sense of self and the notion of a social map. In the absence of national-level caste enumeration, opposition-ruled state governments like Telangana and Karnataka conducted caste surveys. Therefore, it makes political sense for the central government to invalidate the rationale of such surveys by announcing a more comprehensive national-level caste census.

Potentially, a caste census can also bring some political advantages to the BJP. For instance, it might help the BJP’s ongoing outreach towards the non-dominant OBCs and smaller Dalit communities through the implementation of sub-quota, as dominant OBC and SC communities mostly remain consolidated behind the traditional social justice parties. The unpublished report of the Rohini Commission, appointed to design sub-categories within the larger group of OBCs, has reportedly revealed that a few dominant groups within the OBCs have managed to secure a lion’s share of the quota, depriving smaller groups. Furthermore, the inclusion of the Pasmanda Muslims in the central OBC list is also a possibility that may fragment the Muslim votes. Alternatively, incorporation in the central OBC list of new intermediate castes, which are not included in existing state lists, can fuel a campaign that “deserving” Hindu castes have been denied their share of quota to favour Muslims. The Mahishyas in West Bengal constitute one such caste, whom the BJP portrays as the victims of Muslim “appeasement”. Lastly, the announcement of the caste census will puncture a hole in the opposition’s allegation about the BJP’s plan to change the constitution and to do away with reservation.

However, the caste census might also present a host of new challenges for the BJP, such as upper caste backlash, perception about ideological dilution among its core voters and disillusionment among the new generation of aspirational youth willing to embrace meritocracy. But at the moment, caste census appears to be a necessary evil that the party has to swallow. However, to understand the political significance of the caste Census, the presumption of an inherent and inevitable incompatibility between the politics of Mandal and Kamandal must be abandoned.

The writer is a British Academy International Fellow, School of Global Studies, University of Sussex