Opinion Lalu Prasad and Nalin Verma write: A new beginning in Ayodhya and end of an inclusive legacy at Gorakhnath

It's important to underline this legacy especially at a time when the lines between faith and politics are more blurred than ever and over the next week, the nation's eyes will be on the consecration of a temple

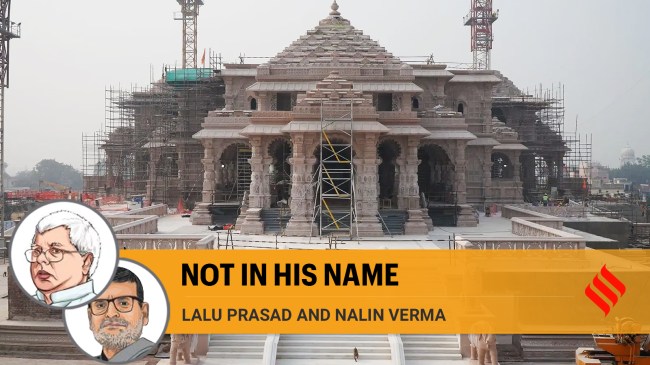

With only a few days to go for the consecration of the Ram temple in Ayodhya, Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Friday said that he will be undertaking a special ritual everyday till the inauguration (Image credit: Shri Ram Janmbhoomi Teerth Kshetra)

With only a few days to go for the consecration of the Ram temple in Ayodhya, Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Friday said that he will be undertaking a special ritual everyday till the inauguration (Image credit: Shri Ram Janmbhoomi Teerth Kshetra) Also by Nalin Verma

As the Ram Temple in Ayodhya marks a new beginning, another temple in Uttar Pradesh comes to mind. Once a symbol of syncretism, the Gorakhnath Math espouses an exclusionary spirituality, promoted by its mahant and Uttar Pradesh chief minister, Yogi Adityanath. It is a paradox that a leader who claims to be a follower of Gorakhnath practises a politics that undermines his legacy of inclusivity.

It’s important to underline this legacy especially at a time when the lines between faith and politics are more blurred than ever and over the next week, the nation’s eyes will be on the consecration of a temple.

According to scholars, Gorakhnath lived in the 11th century and was the founder of the Nath sect of monastic order. His followers are known as yogi, Goraknathi, Darshani or Kanphatta. Adityanath is referred to as “Yogi ji” because he claims to belong to the order of Gorakhnath.

The great Gorakhnath had his followers among both Hindus and Muslims. The first disciple of Gorakhnath was said to be Yogi Vardhanath. It is believed that Gorakhnath, accompanied by Vardhanath, visited the place where the Gorakhnath temple came up and it became known as Gorakhpur later.

The credit for the present form of the temple, spread over 52 acres of land, goes to Mahanta Buddhanath (1708-1723). Historical accounts suggest that Asaf-ud-Daulah, the nawab of Awadh, had donated the land to Baba Roshan Ali, a fakir and devotee of Gorakhnath in the 18th century. It helped rejuvenate the temple and added to its glory and grandeur. The tomb of Roshan Ali, opposite to the temple, constitutes the identity of Gorakhpur.

Gorakhpur is the cultural capital of Deoria, Kushinagar, Maharajganj districts in Uttar Pradesh, and Gopalganj and Siwan districts in Bihar and also parts of Nepal that border these areas in India. The Gorkha community of Nepal is said to have its roots in the sect of Gorakhnath.

The temple was an iconic centre of composite culture till Digvijaynath took over its management in the 1930s. When V D Savarkar became the president of the Hindu Mahasabha in 1937, Digvijaynath became its Gorakhpur chief. He was arrested in the Mahatma Gandhi assassination case. He was the first mahant who entered electoral politics and won the Gorakhpur Lok Sabha seat on the Mahasabha’s ticket in 1967. He died in 1969.

Digvijaynath’s successors, Avaidyanath and Adityanath, groomed themselves as symbols of militant Hindutva in the Gorakhpur region. Avaidyanath represented Gorakhpur in the Lucknow Assembly and the Lok Sabha several times. Adityanath, the present mahant and chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, also represented Gorakhpur in the Lok Sabha five times (1998-2014).

Gorakhnath inspired many love stories in his era, some of which are part of India’s folklore. Ranjha, the main protagonist of the Heer Ranjha story, got solace in his troubled journey of love for Heer when he became the disciple of Gorakhnath. Ranjha and Heer were Muslims. Brijbhar, the protagonist of the Sorthi-Brijbhar story, too, is guided by Gorakhnath, in his journey of love. Gorakhnath also inspired king Bhartrihari to renounce his lust for his consort Pingla and become a yogi.

Noted Hindi writer Hazari Prasad Dwivedi in his work, Nath Sampradaya, says that followers of the Gorakhnath or Nath sect exist across the country. In Punjab, the yogis are called rawal. In Bengal, they go as jugis or jogis. The Awadh and Varanasi regions of Uttar Pradesh and Bhojpur and Magadh regions of Bihar have several yogis. They sing the ballads of Sorthi-Brijbhar, Bhartrihari-Pingla, Heer-Ranjha, and also the bhajans of Kabir, Nanak, Raidas, Dadu and Meera. They sing folk songs for Lord Rama and Shiva-Parvati, to the tune of the sarangee and extol the virtues of Gorakhnath and his guru Matsyendranath. They seek alms, perform magic tricks, suggest herbal cures, read palms and tell fortunes to earn their livelihood. Like rawals of Punjab, the Gorakhnathis are known as darves in Hyderabad and gosawis in Konkan. They are found in Barar, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka, too.

The Nath sect doesn’t accept the supremacy of Brahmins. The followers of the sect chose their gurus from their communities of weavers, dyers, shepherds and agriculturists. Gurus and disciples wander together for alms. Dwivedi says that people from the lower strata of society in both Hindu and Muslim communities — who were looked down upon by the priestly

class — became yogis in the north as well as to the south of the Vindhyas.

Born in Phulwaria village in undivided Saran district of Bihar, bordering Gorakhpur, our generation of villagers grew up with these yogis playing sarangees and singing these ballads. Over the years, these ballads became sources of sustenance for folklorists and folk-theatre artistes who performed at marriage parties and religious events. I am very passionate about these stories. When I became the chief minister of Bihar in 1990, I got the folklorists to perform. I still get them to perform when I find time.

In one of his recordings, the religious personality Osho recounts that once the Hindi poet Sumitranandan Pant asked him to pick 12 major religious figures of India. Osho named Krishna, Patanjali, Gautam Buddha, Mahavir, Nagarjun, Shankar, Gorakhnath, Kabir, Nanak, Mira and Ram Krishna. Pant then asked him to cut down the list to seven, five and then four. Osho picked the names of Krishna, Patanjali, Buddha and Gorakhnath. When Pant asked him to further shorten the list to only three, Osho refused.

Why could he not leave out Gorakhnath, Pant asked. “I cannot leave him,” Osho replied, “because Gorakhnath opened a new avenue and gave birth to a new religion. Without him, there would be no Kabir or Nanak. There would neither be Dadu, nor Wajid, Farid or Meera. The entire Bhakti and Sufi tradition of India are indebted to Gorakhnath. Nobody equals him in his teachings that lead to the discovery of the inner soul.”

Prasad is president of the Rashtriya Janata Dal.Verma is Yadav’s biographer, journalist and a researcher in folklore