Opinion From the Opinions Editor | The kids are not alright: An unprecedented crisis is brewing in schools and homes

Three recent tragedies highlight how rising competition, shrinking emotional support and digital overload are leaving children overwhelmed

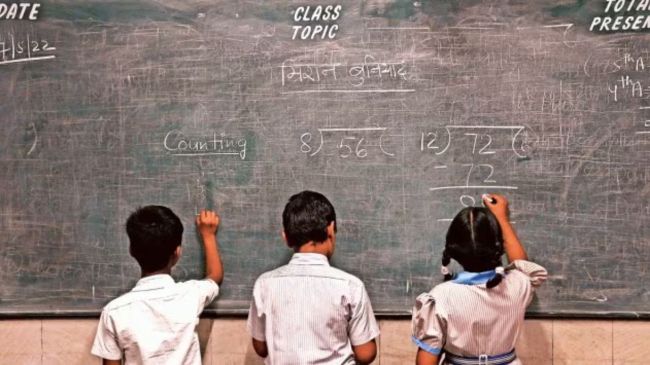

The widening cracks in India’s education system run through classrooms, teacher-student relationships, parental anxieties and the fragile self-esteem of children who learn early that being just so is not good enough. (Representational image/File)

The widening cracks in India’s education system run through classrooms, teacher-student relationships, parental anxieties and the fragile self-esteem of children who learn early that being just so is not good enough. (Representational image/File) Dear Reader,

Days after a Class X student in a Delhi school died by suicide — reportedly worn down by ceaseless public reprimands from some of his school teachers — news of another young life tragically lost emerged from Mumbai’s Kalyan. A 19-year-old first-year college student, allegedly harassed and beaten up by a group of commuters on a local train for speaking Hindi instead of Marathi, returned home and called his father to recount the assault and his crushing feeling of mortification. By the time his family got back, he had died by suicide. Weeks before the two incidents, a nine-year-old Class IV student of a Jaipur school jumped to her death, allegedly after being upbraided by a teacher she believed was persistently and unjustly picking on her.

Three young lives, three stories of distress, three families too many grappling with a profound sense of loss and questions that have no easy answers. There is an unprecedented crisis brewing in Indian schools and homes where young people are struggling to cope with a world harsher than what they are prepared for, as they funnel through narrow academic pipelines, absorb heavy familial expectations, and slip deeper into a digital ecosystem that erodes attention, confidence and connection, the very survival skills that real life demands.

This moment of rupture also sits within a coarsening social temperament. School corridors and college politics remain combative in tone and impatient with vulnerability. The inevitable corollary is bullying — both online and offline — that is normalised as assertion. The student on the Mumbai local attacked for speaking the “wrong” language therefore becomes not an outlier but part of a broader culture that rewards aggression and calls it strength.

The widening cracks in India’s education system run through classrooms, teacher-student relationships, parental anxieties and the fragile self-esteem of children who learn early that being just so is not good enough. Prestigious institutes — IITs, IIMs, AIIMS — remain symbols of aspiration and social prestige, but seats are few and the competition fierce. More than 1.3 million students registered for JEE (Main) in 2025 for a little over 18,000 IIT seats. Those who fall short often internalise it as existential failure. “Mummy papa, I can’t do JEE… I am a loser. Worst daughter… This is the last option,” the desperation is evident in the note left behind by 18-year-old Niharika Solanki, the eldest of three daughters of a security guard, who died by suicide in Rajasthan’s Kota last year. Data underscores the severity of the crisis: According to the National Crime Records Bureau’s 2023 report, 13,892 students died by suicide that year — the highest in a decade — rising from 8,423 in 2013. As opportunities contract, every examination feels like a referendum on one’s worth, especially for those for whom education remains the only viable path to social mobility.

This sense of walking a tightrope creeps insidiously into schools in secondary years, when children must deal with the vocabulary of ranks, percentiles, and cut-offs. Despite the promise of the New Education Policy (NEP) 2020, teachers, too, become enforcers of this culture of measurement — the “good student”, the “obedient child” is rewarded while the “misfit” and the vulnerable is left behind.

If the classroom is one arena of performance, the other unfolds on the smartphone, in the curated glare of social media. In The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness, American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt writes, “Gen Z became the first generation in history to go through puberty with a portal in their pockets that called them away from the people nearby and into an alternative universe that was exciting, addictive, unstable, and… unsuitable for children and adolescents.” As parents navigate this new world they have no map for, lurking beneath a montage of manicured triumphs is a corrosive prescription for low self-worth, a need for constant validation, anxiety and other mental-health afflictions that now affects a sizeable portion of Gen Z across the world. Platforms built to “connect” manufacture loneliness at scale. Children who spend hours online report higher levels of isolation as they lose the slow, awkward, necessary practice of building friendships face-to-face; of sitting with moments of boredom that foster imagination; of learning to resolve small crises on their own.

What, then, is the solution?

Perhaps it begins with a willingness to listen without rushing to diagnose or discipline, with an acknowledgement of the fears and anxieties of the young without folding them into moral lessons. What the young and the fragile need are people — teachers, parents, family — who can sit with their uncertainty, and stay with them through difficult conversations without judgement; friends and strangers who show up in small, steady ways.

None of this will insulate children from the inevitable pain and pressures of adolescence and youth. But in a society impatient for success, the act of making room for tenderness can give them what the moment most denies the young: The assurance that they do not have to navigate the hardest parts of growing up alone.

Stay well,

Paromita

Recommended Readings:

P B Mehta writes on SC ruling on governors: An obligingly ambiguous piece of judgment

Congress should stop playing victim

Bihar shows old Opposition getting eased out, new Opposition not in sight

More than two decades later, at end of the red corridor, there is light

Four labour codes, one big leap