Opinion Kafka and László Krasznahorkai’s legacy is a reminder — to write is to defy the silence of a fractured world

Krasznahorkai’s response to winning the Nobel was emblematic of this lineage: “I never wanted to achieve anything with my books. I just wanted to tell the stories I needed to tell.”

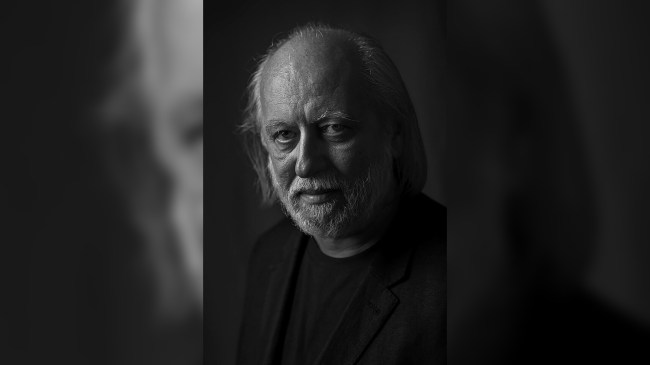

Krasznahorkai, the 2025 Nobel Prize winner in Literature

Krasznahorkai, the 2025 Nobel Prize winner in Literature BY Vipul Anekant

“When I am not reading Kafka, I am thinking about Kafka. When I am not thinking about Kafka, I miss thinking about him. Having missed thinking about him for a while, I take him out and read him again.”

László Krasznahorkai, ‘The White Review’, 2013

This reflection by Krasznahorkai, the 2025 Nobel Prize winner in Literature, is a candid confession of influence, platonic communion and a near-mystical devotion to Franz Kafka. In his writing, he inherited Kafka’s existential burden, reconfiguring it into a transcendent vision of the world.

Kafka’s works, etched in the early 20th century, map the contours of existential dread, where faceless bureaucracies ensnare the individual in a labyrinth of futility. In Krasznahorkai, we encounter a philosophical heir who transforms Kafka’s vision into a neo-Kafkaesque meditation — a symphonic reckoning with a world teetering on the edge of apocalypse, where literature becomes both witness and salvation. Krasznahorkai’s novels, Satantango and The Melancholy of Resistance, are not mere extensions of Kafka’s dread but its culmination, transforming individual alienation into a collective elegy for a decaying world.

Kafka once wrote, “I am writing because it is difficult not to write, and knowing well that it is difficult also to write. Seeing no way out of it, I am writing.” This encapsulates a secular mystic’s agony — an awareness of truths beyond language’s grasp — akin to the Eastern concept of anirvacaniyata, inexpressibleness.

Krasznahorkai walks this same edge. His prose, marked by weighty, rolling syntax that eschews conventional punctuation, invites readers into a meditative landscape where language becomes a terrain of thought. As The Paris Review noted, Krasznahorkai extends Kafka’s dread “into an era where bureaucracy has become theology”.

Krasznahorkai bridges cultures through his travels in Japan, Mongolia, and China. His early novels, steeped in despair, evolve into a sacred stillness in his later works. Nobel Committee member Steve Sem-Sandberg noted, “He also looks to the East in adopting a more contemplative, finely calibrated tone.”

Kafka reportedly burned 90 per cent of his works. In an anguished confession, he instructed his close friend Max Brod to destroy all unpublished manuscripts, diaries, and sketches after his death, writing, “This is the only way I can get rid of that constant anxiety that I have been trying to say something which cannot be said… The pieces I could send really mean nothing at all to me, I respect only the moments at which I wrote them.” This embodies the tragedy and beauty of Kafka’s absurdism.

Krasznahorkai, too, probes reality to the point of madness, as he once described his work. Yet this madness elevates Kafka’s introspective dread into a cosmic meditation on collapse and resilience. In his vision, despair becomes meditative, decay becomes lyrical, and stillness becomes resistance — not fatalism but a sacred witnessing.

Krasznahorkai’s response to winning the Nobel was emblematic of this lineage: “I never wanted to achieve anything with my books. I just wanted to tell the stories I needed to tell.”

Krasznahorkai’s candidness shines in his unpolished, introspective responses. In a 2012 London Review Bookshop interview, asked whether his apocalyptic, transcendental prose pointed toward God, he paused and admitted, “The question is wonderful, but I couldn’t answer. It’s too difficult for me. I’m not that clever.”

This honesty marked his first interview after winning the Nobel. Echoing Samuel Beckett’s “What a catastrophe,” Krasznahorkai called his win “more than a catastrophe” yet “a source of happiness and pride”. He spoke not with detachment, but with gratitude for joining great writers, writing in Hungarian, his readers, and the power of imagination.

Both writers share an unguarded sincerity and unwillingness to retreat into cleverness. Krasznahorkai urged readers to reclaim imagination, reading, and fantasy to survive “very, very difficult times on Earth”. Unlike Kafka, for whom reading was an existential escape, for Krasznahorkai, it is survival, an act of endurance. Unlike Kafka, who wished his works burned, Krasznahorkai embraced the value of disseminating his art.

Neither wrote for posterity — Kafka out of the impossibility of not writing, Krasznahorkai out of a yielding necessity. Where Kafka burned with the anxiety of silence, Krasznahorkai ruminates within it, shaping it without conclusion — the continuation of an unending sentence.

In this philosophical continuum, Kafka left the unresolved tension of being — the beauty of paradox embraced but never overcome. As the 2025 Nobel laureate, Krasznahorkai internalises this paradox into meditative resistance. His prose becomes a beacon, affirming literature’s power to face the ineffable and find transcendence in the ruins. Kafka and Krasznahorkai’s shared legacy reminds us: To write is to defy the silence of a fractured world, to shape what cannot be spoken, and to find meaning in the act itself.

The writer is currently Deputy Commissioner of Police, Delhi Police