Opinion In Palestine-Israel war, the violence of pure identity

The historical roots of contemporary Israeli-Jewish identity lie in acts of forgetting actual relations on the ground. Brute force – both Israeli and of its western allies – has ensured periods of unstable and inherently fragile peace

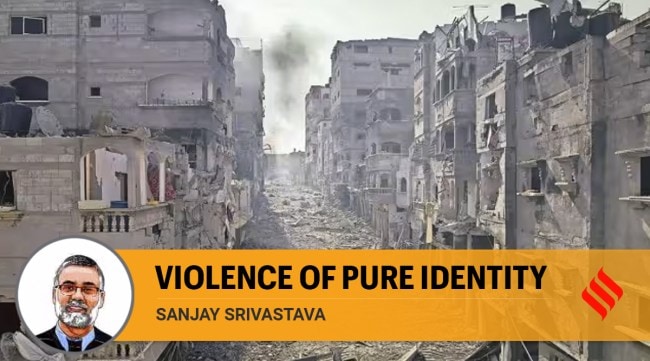

A view of the rubble of buildings hit by an Israeli airstrike, in Jabalia, Gaza strip, Wednesday, Oct. 11, 2023. Israel has launched intense airstrikes in Gaza after the territory's militant rulers carried out an unprecedented attack on Israel Saturday, killing hundreds of people and taking captives. Hundreds of Palestinians have been killed in the airstrikes. (AP Photo)

A view of the rubble of buildings hit by an Israeli airstrike, in Jabalia, Gaza strip, Wednesday, Oct. 11, 2023. Israel has launched intense airstrikes in Gaza after the territory's militant rulers carried out an unprecedented attack on Israel Saturday, killing hundreds of people and taking captives. Hundreds of Palestinians have been killed in the airstrikes. (AP Photo) The recurring tragedy that is the Palestine-Israel relationship should have something to tell us about the dangers of interpreting human histories through the constraining lens of religious imagination. It should also warn us against thinking that colonial ideas about identity and community have “ancient” — hence local — origins. Palestine’s tragedy — and the extraordinary human suffering it has caused — is a cautionary tale for all societies that seek to flatten complex histories of co-existence among populations into the fiction of the “superiority” of any one group over others.

The history of the so-called Promised Land (Eretz Israel) that, according to Jewish tradition, rightfully belong to Jews, is one of both shifting narratives about borders and mythic memories. In an ancient land, controlled at different times by a multiplicity of ruling powers and settled by just as heterogenous mix of populations, the territories of Eretz Israel have always been in flux. Historians of the region — those not beholden to either the Israeli or Palestinian advocacy circle — suggest that even Jewish sources have differing accounts of the boundaries of the territory apparently promised by god to the Jewish people.

Historians also point to a further complication — one of many, given the nature that the region is situated at the cultural and social crossroads of great complexity. It pertains to the exclusionary claims to territory put forward by one group. If biblical claims to territory are to be accepted as grounds for occupation, then a particular complication of identity comes into play. The entangled histories of the people of the region also give us entangled lineages of holy personages. This, in turn, does not give us any straightforward story of one group having clear rights to ownership of land by virtue of a covenant between its ancestors and god. This “ancestry” is — for the purposes of claiming an exclusive identity — not at all clear cut or exclusive. For, the descendants of Prophet Abraham — whose special relationship with god is at the heart of Jewish ideas about the Promised Land — are also those the Muslims claim as their own. How then to claim that a particular piece of land can be attributed clear ownership such that all others — with equally strong proof of their connection — must be excluded?

This is where the story of Zionism, colonialism and the self-serving role of western powers come in. Religious texts are not historical documents but their use as such can convert them into instruments of historical injustice and contribute to human suffering. A significant part of the modern history of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict lies in the flattening of histories of co-existence and belonging to produce black and white narratives of origin. Though historians have struggled to find irrefutable evidence of a Promised Land, politicians and British colonialists did not have any such difficulty. They achieved this through producing narratives that completely severed the historical cultural and social links between the Muslims and Jews of the region. This could only be done through inventing a modern history of Jewish (and hence Muslim) identity that sidestepped the long history of interactions and mutualism among them.

The modern idea of the Promised Land required the making of an exclusive identity which could, in turn, lay exclusive claim to this imagined territory. The collapse of the Ottoman empire, the so-called Balfour Declaration of 1917 (that expressed British support for Jewish homeland), and colonial rivalry between the British and French provided fertile conditions for the making of a Jewish identity — and the Promised Land — which drew upon a biblical tradition with no basis in history — or, at least, a history that neutral historians might recognise as such.

The colonial arrangement known as the British Mandate of Palestine (1918-1948) eventually gave way to the partitioning of lands occupied by Arabs and the creation of the Israeli state. The invention of a modern religious mythology — that of definitive Promised Land — was a collaborative project between the European Zionist movement, the colonial powers and an international body that largely represented the interests of the latter, the United Nations. The establishment of the Israeli state was a direct result of the ideology of the zero-sum game: Occupants of hundreds of Arab villages fled their homes, their dwellings razed to the ground. A large-scale influx of Jewish immigrants into the new country ensued and this population started its life in Israel as the new owner of Arab property and other resources.

It was fair of the Arabs to ask – as many did – if they were being made to suffer for European guilt about the historical treatment of their Jewish populations.

Just as histories of territories are invariably mongrel, so are traditions and customs. Attempts to discard such hybridities in the Middle-East and establish a national identity in the name of a “pure” identity – enforced through military and economic might – have not led to a lasting solution. The key outcome has been only more bloodshed, generations of young people growing up in violence and the despair that invariably and periodically manifests as further violence.

The historical roots of contemporary Israeli-Jewish identity lie in acts of forgetting actual relations on the ground and reaching out to a mythical — ancient, textual — past. Brute force — both Israeli and of its western allies — has ensured periods of unstable and inherently fragile peace. It can only ever be this way in all contexts where identities and aspirations are either fostered or constrained through the force. For force always attracts counterforce, particularly from those who have nothing more to lose.

Finally, while there are differences between Indian and middle-eastern modernities, there are similarities too. We too nowadays seek to recast Indianness through by-passing certain epochs and reaching out to an “ancient” and “unsullied” period. And the Indian present is also characterised by an urge to constrain the expression of multiple identities –that actually exist – in favour of a monolithic one that is sought to be established by force. The Israeli path to national identity-formation should convince us that that is a highway to a recurring tragedy.

The writer is British Academy Global Professor, Department of Anthropology and Sociology, SOAS University of London