Opinion Imran Khan’s arrest: He had it coming

The former Pakistan PM underestimated the military’s powers, made no attempt to strike a consensus with civilian political forces

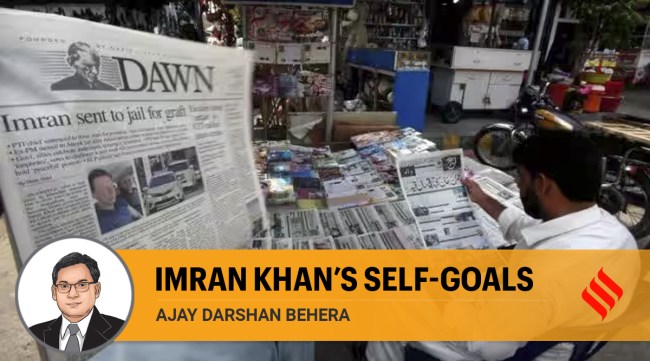

Questions have been raised about the fairness of the trial and there has been widespread condemnation and much debate. (File photo)

Questions have been raised about the fairness of the trial and there has been widespread condemnation and much debate. (File photo) Former Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan was arrested last Saturday on charges of “corrupt practices”, a development many did not find surprising. Khan was accused of failing to correctly declare certain gifts he had received during his tenure as PM. The Islamabad trial court handed down the maximum sentence for the offence the former Pakistani PM was charged with — three years in prison and a fine of Rs 1,00,000, imposed on him for concealing details of the toshakhana gifts. As a result, Khan is disqualified from holding public office for five years.

Questions have been raised about the fairness of the trial and there has been widespread condemnation and much debate. But the verdict is not unprecedented. In the past, top political leaders in Pakistan, including prime ministers, have been sentenced and disqualified from holding public office. Imran has a right to appeal, and it’s very likely that we will see a prolonged legal battle. But the purpose of the verdict seems to be to ensure that Khan is no longer a player in the next general elections, likely to be held in November this year — though there are speculations that they could be postponed.

Khan has been besieged with legal trouble after he was removed from power in a no-confidence vote in parliament in April 2022. More than 140 cases have been filed against him — they include charges of corruption, terrorism and inciting violence. Khan did not admit to any wrongdoing and contended that the cases were politically motivated. On May 9, he was arrested inside the Islamabad High Court by the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) on corruption charges related to the Al-Qadir Trust.

The PTI promptly called for demonstrations. Attacks by Khan’s supporters on government and military property across Pakistan on May 9 undermined the former PM’s objective of pushing back the military. The attacks provided the army and the civilian opponents an excuse for resorting to harsh measures. Khan’s reckless call for street protests actually opened the door for the military to enlist the support of the civilians opposed to him.

After floating his party in 1996, Imran was able to come to power in 2018 with the support of the military establishment. The general elections were believed to have been heavily rigged in the PTI’s favour. The military’s interest in propping up Khan was to create an alternative to the PML(N) and the PPP, which had differences with the generals. The assumption was Khan would be more pliable. During his tenure as prime minister, Khan was seen to be working in a close relationship with the military. His fallout with the military was due to differences over army postings. Imran’s anti-US stance was seen as hurting Pakistan and hastening the deterioration of the country’s economic situation. Khan had become a liability to the military and he was inept at steering the failing economy. The army withdrew support and the no-confidence motion against him succeeded.

The PDM formed in 2020 as an alliance of 11 opposition parties, united in their aim to challenge the PTI-led government, came to power. It has been vocal in its criticism of Khan’s administration, targeting issues such as economic mismanagement, corruption and erosion of democratic values. In a change of circumstances, the interests of the PDM and military have converged — they want to make Khan irrelevant in the electoral fray. This is a recurring feature of Pakistan’s politics — civilian supremacy gets undermined by the machinations of political parties. This will have short-term and long-term consequences for Pakistan’s democracy.

Khan’s strategy after being ousted from power has weakened parliament. His attacks on both the military and the civilian leaders gave no space for a consensus. His tactic of forcing the establishment to hold elections by street protests deepened the political divide. The former PM has been brave in confronting the military, but short-sighted in understanding the grip the military has on Pakistan’s politics.

He should have also realised that politicians and political parties are useful to the military only to a point. Imran’s refusal to compromise with civilian leaders has actually empowered the military generals and strengthened their grip on politics.

The irony is that Khan is a victim of political vindictiveness he had resorted to during his tenure as the PM. His disqualification bears resemblance to the Pakistan High Court’s 2017 decision to disqualify Nawaz Sharif on flimsy grounds of receiving an illegal salary. Sharif’s daughter and brother Shehbaz Sharif were also in the custody of the NAB during Khan’s tenure as PM. He also tried to destabilise the provincial government of Sindh in 2019. Top PPP leaders were incriminated in a money-laundering scam, by accounts because Khan wanted to push them out of the electoral fray. In Pakistan’s politics, the judiciary and NAB have become convenient tools to get rid of troublesome politicians.

Khan’s arrest will sharpen the divide in an already polarised polity. Accountability is crucial in any democratic system. But in Pakistani politics, it’s often used selectively — for political manipulation. The political uncertainty surrounding Khan’s arrest could impact investor confidence and aggravate Pakistan’s economic difficulties. Imran’s future in politics remains uncertain. One thing is, however, clear: We have not seen the last of this issue. The final outcome will depend on the legal proceedings and the verdicts of the higher courts. But Saturday’s verdict could push Pakistan into a political quagmire. It’s a test for the country’s political institutions.

The writer is Professor Academy of International Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi