Opinion Hijab or an education: What choice did Class XII topper Tabassum Shaik really have?

The hijab ban forced her to give up the headscarf in order to pursue her education. It was a choice born out of circumstance, not privilege

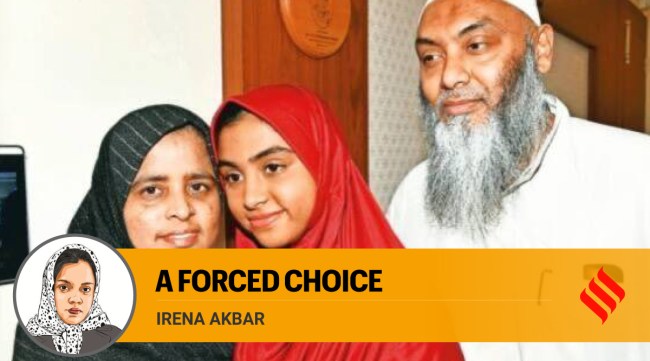

Tabassum Shaik with her parents Abdul Khaum Shaik and Parveen Modi. (Express Photo by Jithendra M)

Tabassum Shaik with her parents Abdul Khaum Shaik and Parveen Modi. (Express Photo by Jithendra M) In an interview published in The Indian Express on April 22, Tabassum Shaik, the Arts stream topper of the Class XII exam held across pre-university colleges in Karnataka, said, “Between education and hijab, I chose education. We will need to make some sacrifices to accomplish bigger things.”

In January 2022, the Karnataka government prohibited the wearing of the Muslim headscarf across government PUCs (pre-university colleges) after protests erupted over a group of Muslim students being barred from their classroom for coming in their hijabs. Within a month, the Karnataka High Court upheld the ban.

Tabassum, who till then would wear a hijab to school, had to decide what to prioritise — wearing her hijab, or going to college. “I decided to give up the hijab and pursue my education,” the 18-year-old said in the interview.

Tabassum’s “choice” was not born out of privilege, but out of circumstance. The ban on the hijab forced her into making a choice. When circumstances force you to make a choice, is it really a choice? Is it a choice made out of “free will”, or against it?

In Tabassum’s own words, her “choice” involved “sacrifice”, that is, sacrificing the hijab, a symbol of religious identity for many Muslim girls and women. She would wear a headscarf till the gate of her college, and then had to remove it in a room before she could enter the classroom.

Choices that involve sacrifices or compromises are essentially a coping mechanism that help you survive difficult situations. Tabassum did not just cope and survive, she came out an inspiring winner, scoring 593 out of 600, with a perfect 100 in Hindi, Psychology and Sociology.

Tabassum’s success, however, does not mitigate the failure of the state in providing equal, unhindered access to education to all students. Tabsassum did not have equal or unhindered access to her classroom. The hijab ban was a hindrance, and she had to work her way around it to continue her education. It’s a telling example of inequality, given that no non-Muslim student or no non-hijabi Muslim student had to go through the checkpoint of removing a piece of harmless clothing in a separate room before being allowed to enter the classroom or write an exam.

Many Muslim students could not even reach the checkpoint. Some dropped out of government PUCs, enrolling in private colleges instead. Some lost an academic year, as students of all PUCs have to write their annual exams in a government PUC, where wearing the hijab is illegal. They now await the Supreme Court’s verdict on the matter. Last October, the apex court delivered a split verdict, effectively maintaining the status quo.

One may ask: Why didn’t other Muslim students follow Tabassum’s example? But here’s a clutch of counter-questions: Why should a Muslim student be burdened with such difficult choices? Why should their right to practise their faith be pitted against their right to study? Why does a Muslim student have to be exceptionally brilliant and strong, and make it to the headlines? Why do they not have the freedom to be average, to not be strong enough to “sacrifice” a symbol of their faith, their identity in their tender teenage years?

Tabassum’s parents are visibly Muslim: Her mother wears a burqa, and her father a thick beard and topi. But the parents advised their daughter to suspend her visible religiosity at college in order to follow the “law of the land”.

In the last two years, the BJP-led state government has passed laws that are designed to put Muslims in the dock: The Karnataka Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle Act 2020 to “fight cow slaughter”, the Karnataka Protection of Right to Freedom of Religion Act 2021 to “fight love jihad” and the 2022 hijab ban rule under the Karnataka Education Act.

As Karnataka heads for elections next month, there have been increasing calls by Hindu right-wing groups for banning halal meat and azaan and for boycotting of Muslim shops near temples.

In this larger picture of anti-Muslim politics in Karnataka, and by extension, India, it’s important to question why Tabassum had to make a choice at all. Even as Tabassum’s success story is worthy of celebration, it must not be used to disprove the discriminatory nature of the hijab ban or worse, justify it. Tabassum’s feat is her own, and she achieved it despite the hijab ban, not because of it.

Akbar is an entrepreneur and freelance writer