Opinion Scholar and teacher Gopichand Narang believed in Urdu’s ability to build bridges

Rakshanda Jalil writes: While Gopichand Narang lived a rich life, amply studded with awards and encomiums, his real contribution lies in a life-long commitment to a scholarship that was dynamic, innovative and alive to changing social realities.

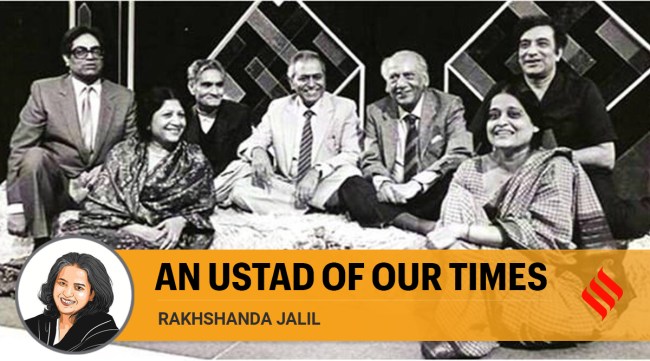

Iftikhar Arif, Jameela Dehlvi, Shohrat Bukhari, Gopi Chand Narang, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Zehra Nigah and Ahmed Faraz.

Iftikhar Arif, Jameela Dehlvi, Shohrat Bukhari, Gopi Chand Narang, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Zehra Nigah and Ahmed Faraz. Gopichand Narang passed away on Wednesday in Charlotte, USA, surrounded by his family. He was 92. With him an era of Urdu studies ends, for he was the last of the great Urdu ustads of modern times. In a long and illustrious career as a teacher of Urdu, a writer and critic of depth and gravitas, an engaging and eloquent speaker, a tireless organiser of seminars, symposiums and academic interventions, an indefatigable champion of the cause of Urdu, Narang sahab had single-handedly done more for the cause of Urdu in India than many anjumans and associations. His list of publications was formidable, and so was his command over the intricacies of linguistic theory and cultural praxis. What was most heartening, however, was his lifelong belief in the innate ability of Urdu to build bridges, to forge interfaith harmony and emerge as the pre-eminent symbol of composite culture.

I had known Narang sahab as a friend of the family virtually my entire life, but my first real engagement with his work began when I was writing my thesis on the Progressive Writers’ Movement in Urdu. I found his seminal work Tehreek-e Azaadi aur Urdu Shairi to be by far the most authoritative study of the post-1857 Urdu literature. What was also interesting was and, in a sense, it bolstered my own fledgling understanding of socially-engaged, socially-purposive literature, was how he viewed 1857 as a significant milestone in the evolution of what he called wataniyat (nationalism) in Urdu poetry. In giving the example of Raja Ram Narain Mauzoon who wrote this sher at the death of his friend Nawab Siraj-ud-daula of Bengal who was killed by the British in the Battle of Plassey in 1757: Ghazala tum to waqif ho kaho Majnun ke marne ki/Diwana mar gaya akhir ko wirane pe kya guzri

Narang sahab drew our attention to how Majnun, the legendary lover of Laila-Majnun fame, becomes here a metaphor for Siraj-ud-daula who fired the imagination of many Indians by his heroic resistance to the British. Elsewhere, he cites literary commentaries, compilations of sheher ashob, volumes such as Fughan-e Dehli, texts and commentaries of Maulvi Zakaullah and Zaheer Dehelvi, to paint a very real picture of defeat and despair where people lived lifeless and spiritless lives (bejaan aur berooh zindagi jii rahe thhe). It was only with the dawn of the 20th century, Narang sahab goes on to demonstrate that hubb-e watani (love for the nation) as we understand it today was born and, what is more, found ample reflection in Urdu poetry. I found all this of great value to me in building my entire thesis that nationalism was not a foreign construct, nor was socially-engaged literature an exotic hybrid imported from the Russian motherland and grafted on to Indian soil. It was 1857, really, that caused a burst of political consciousness to seep out and colour our understanding of the world. It changed our ways of seeing the world and, by extension, it changed our literature. I owe a debt of gratitude to Narang sahab and his seminal work on 1857 which in a sense formed the basis of my own understanding of the ghadar and by extension the close relationship between social reality and literary texts.

So, today is as good a day as any to acknowledge this debt.

Another thing that I, as neo-convert to Urdu studies generally and to Urdu literary history in particular, have benefitted enormously from is Narang sahab’s fondness for putting his thoughts down in a tabular fashion. This is a modern, scientific way of elucidating complex ideas. In his latest book, Urdu Ghazal: A Gift of India’s Composite Culture (OUP), as in some of his earlier work he uses the table to explain the basic love triangle of the ghazal’s metaphoric structure, the love triangle between the aashiq, the mashuq and the raquib and the many associated metaphors.

Given the recurring controversy over Faiz and his Hum Dekhenge, I am again reminded of Narang sahab’s excellent essay, “Tradition and Innovation in Faiz”, which talks of Faiz and his use of classical imagery for political themes. Locating Faiz in the same trajectory as Chakbast and Hasrat Mohani, Narang sahab places the progressive poetry of Faiz in the centuries-old shehr ashob tradition. However, unlike the dirge-like laments that were the shehr ashob, Faiz broadened the scope of time-honoured images and symbols and infused a new life and urgency in them. Briefly, some of the most commonly used terms in Faiz’s poetry, as identified by Narang sahab which have been invested with a new political agency, are: Ashiq, raqib, ishq, deedar, hijr, firaq, sharab, maikhana, pyala, saqi, zindan, daar-o-rasam and so on.

While Narang sahab lived a rich life, amply studded with awards and encomiums (Padma Bhushan, Moortidevi Award, Sitar-e Imtiaz, Iqbal Samman, to name a few), over 65 books in Urdu, Hindi and English, his real contribution lies in a life-long commitment to a scholarship that was dynamic, innovative and alive to changing social realities.

Jalil is a Delhi-based author, translator and literary historian