A free terrorist and a carefree Musharraf

Two seemingly unrelated developments over the last few days bring into question the intentions of Pakistan’s present military oligarchy...

Two seemingly unrelated developments over the last few days bring into question the intentions of Pakistan’s present military oligarchy, which continues to present itself as a reforming regime working towards a transition to democracy.

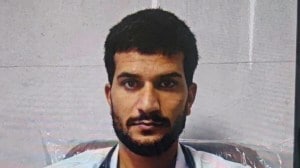

The first was the release of Jaish-e-Muhammad leader Masood Azhar, ostensibly under the orders of a court. General Pervez Musharraf banned Jaish earlier in the year for being a terrorist organisation. Maulana Azhar was reluctantly put under house arrest after much pressure from the United States on account of his public advocacy of suicide bombings and his statement accepting responsibility for last year’s October 1 attack on the legislative assembly building in Srinagar. The court ordering his release said the government had failed to make the case for his continued detention under the Public Safety law, raising the question whether the government really wanted to keep him detained. After all, once it decides to keep someone in prison, the Pakistani government can find a hundred ways to attain its objective.

Musharraf purged the superior courts soon after his coup under his Provisional Constitution Order and the courts have been virtually subservient to the executive ever since. Pakistan’s prosecuting authorities have never been independent of political decisions, making Masood Azhar’s case all the more troubling. If Musharraf and his government did not have evidence to consider Jaish-e-Muhammad a terrorist organisation, why did they ban it? And if such evidence does exist, why was it not used to extend Maulana Azhar’s detention? Whichever way one looks at it, the government’s hands are far from clean.

The second manifestation of the disturbing trend of Musharraf’s policies was the ‘‘election’’ of the new Sindh Chief Minister. The Sindh assembly was convened 62 days after its election, the longest delay in the convening of any provincial assembly in the country. It was cobbled together by the Intelligence services, which brought disparate elements and individuals together to deny the PPP, the single largest party in the province, the right of trying to form a coalition. To accommodate the demands of the largest coalition partner, the Mutahhida Qaumi Movement (MQM), terror was unleashed against its local rival and breakaway group, the Muhajir Qaumi Movement (commonly known as MQM-Haqeeqi).

|

If Musharraf didn’t have evidence to consider the Jaish a terrorist organisation, why did he ban it? If such evidence did exist, why wasn’t it used to extend Azhar’s detention? |

By all accounts, the new Sindh government is likely to follow in the footsteps of a similar anyone-but-PPP regime unleashed on the province between 1990-1993. The then Chief Minister, Jam Sadiq Ali, was handpicked by the intelligence services in the same manner as Ali Mohammed Maher has been chosen. Then as now, the majority within the coalition belonged to the urban-based Urdu-speaking MQM, which was accused of controlling Sindh’s cities with the help of its private militia.

It is obvious that notwithstanding his promises to his US allies, Musharraf’s overall gameplan for Pakistan is not different from that of his predecessors. He considers civilian politicians like Benazir Bhutto a greater threat than leaders of groups that he has himself named as terrorists. The military establishment’s invisible fixers continue to muddy Pakistan’s political water. But the military and its apologists routinely deny they have anything to do with whatever is going on. They want the world to believe that the court released Masood Azhar and that the political wheeling and dealing is the handiwork of the politicians.

Soon after he assumed power, General Musharraf managed to convince many Pakistanis of his good intentions. Over the last three years, he has not been an easy man to define. He rules by decree while professing to build a democracy. He supported the Taliban only to become famous for his role in their destruction. He seeks dialogue with India without hiding his belief that India is Pakistan’s eternal enemy. He enjoys and clings to power while claiming he came to it by accident.

In a recent interview, Musharraf revealed that Richard Nixon and Napoleon are his leadership models. Perhaps that is the most telling revelation about him: neither Nixon nor Napoleon was particularly known for following rules as for them the end justified their means. And the end for both of Musharraf’s leadership models was none other than wielding and accumulating power.

Musharraf has so far ruled with the help of a small group of close military friends. He has avoided a reputation for repression and has allowed a relatively free press. But he does not believe in legal niceties if and when he needs to get tough. He demonstrated his willingness to take risks by abandoning support for the Taliban and took on Pakistan’s own Islamists. But his promises of reform remain unfulfilled and he seems to be going back on most of his promises. It is Pakistan’s misfortune that he has turned out to be just another military ruler who thinks all is well as long as he is in charge.

E-mail the Author

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05