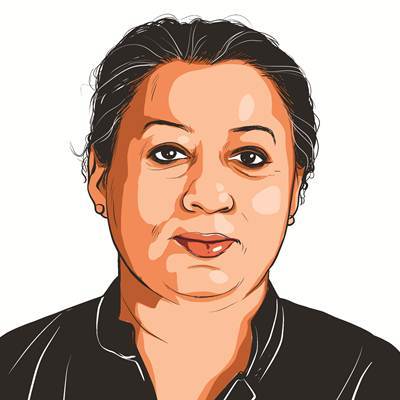

Ritu Sarin is Executive Editor (News and Investigations) at The Indian Express group. Her areas of specialisation include internal security, money laundering and corruption. Sarin is one of India’s most renowned reporters and has a career in journalism of over four decades. She is a member of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) since 1999 and since early 2023, a member of its Board of Directors. She has also been a founder member of the ICIJ Network Committee (INC). She has, to begin with, alone, and later led teams which have worked on ICIJ’s Offshore Leaks, Swiss Leaks, the Pulitzer Prize winning Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, Implant Files, Fincen Files, Pandora Papers, the Uber Files and Deforestation Inc. She has conducted investigative journalism workshops and addressed investigative journalism conferences with a specialisation on collaborative journalism in several countries. ... Read More

A capital `I’ as in CBI

The spanking new waiting room near the reception is a welcome addition to the facilities of the country's super-sleuthing agency, the Centr...

The spanking new waiting room near the reception is a welcome addition to the facilities of the country’s super-sleuthing agency, the Central Bureau of Investigation. Ever since Joginder Singh, 58, the loquacious and by-now controversial Director took charge, media persons had set up shop outside the CBI’s headquarters. At any time of the day, members of a careworn TV crew can be spotted cooling their heels outside the building or an expectant scribe or two loitering in its precincts.

Finally, the pack of Joginder-joggers will get to sit back comfortably on a sofa and wait for the relevant soundbytes to flow in quotes from the man who is arguably the most accessible CBI Director in decades.

Singh has been in the hot spot for about 10 months now, but it is time enough for journalists on the CBI beat to figure out what the accessibility, he is so fond of talking about, really means.

A typical “encounter” between the ever-smiling Director and the anxious scribe scouring his file-laden desk (the standard teak-wood desk has been replaced by a glass-top one, in an effort to connote transparency perhaps!) for scoops, progresses as follows. The ground-rules are fairly standardised. The CBI’s affable information officer, S.M. Khan, is invariably at hand. The Director begins the discussion by first setting the stop-watch he is wearing to the time allotted for the encounter.

The scribe runs through titles of the most important cases presently being handled by the CBI. “Purulia?” Joginder Singh asks incredulously. “That case has already been solved.” The interviewer persists with the question: “The most important thing is where the arms were headed for. Does the CBI have the answer?”

“Yes, yes,” Joginder Singh says, waving his hand dimissively, “We have enough proof that the arms were meant for the Anand Margis. I will give you ALL details when we meet next.”

The next volley of questions also elicits nothing tangible. “Urea chargesheet?” Joginder Singh asks next. “They will be filed in the next few days. Yes, you can have THOSE details. I will call the officer right now.”

The Director calls in one of CBI’s legal advisors, who informs him that as far as the urea case is concerned, the investigations were incomplete both in India and abroad. The officer leaves the room and the Director faces the correspondent again. “Never mind, hum aapko khali haath nahin janee dein ge…” (we won’t send you empty-handed).

He hands over copy of a letter he has recently written to the Home Secretary reminding him that the request for prosecution of a former bureaucrat was long-pending with the Government. Silenced but not satisfied, the correspondent departs-but only after getting an assurance about a quick, more newsy meeting soon.

Gregarious and media-savvy, Joginder Singh has obviously grown into the job and has learnt how to brandish the double-edged sword that his open-door policy has proved to be. He had a disastrous start when, as part of his initiation into the job, he called on former Prime Minister Narasimha Rao, an accused in more than one of his cases. Then came the spate of strictures, one from some Supreme Court judges who upbraided him for “hobnobbing” with politicians.

“From this very moment, I will become a total recluse,” Joginder Singh had assured the honorable Justices, but within days he was busy eating his words. Clearly, the life of a recluse was not for this IPS officer, who was well-known for his networking abilities during his morning constitutionals at Delhi’s famed Lodhi Gardens.

Earlier, after work, he boasted of spending his time reading and re-reading feel-good maestros Dale Carnegie and Vincent Peale. He later took to writing manuals on self-development and, finally, novellas on crime.

Now Joginder Singh maintains that two-thirds of his day is spent poring over case records and the little time that is left, is utilised meeting his “friends” a large number of whom belong to the press. CBI insiders claim that Joginder Singh’s pre-occupation with case files is hardly surprising since he has centralised everything and has the habit of calling for the files pertaining to all the sensitive cases at hand. And, they say, after issuing “gag” orders forbidding his subordinates from speaking to the media, Joginder Singh hardly ever formally allows a journalist access to a senior CBI officer.

Yet, ironically, he himself appears to be media friendly, despite the fact that the “interviews” he grants to journalists may be full of platitudes and self-praise. He may not have “leaked” many of the documents that politicians allege he did, but no one is willing to believe him for the moment. His critics point out that if Joginder Singh had to take audacious steps like processing the case for prosecuting Laloo Prasad Yadav and the others accused in the 10-year-old Bofors case, why did he do it after Deva Gowda demitted office?

The frailty of “Tiger” Joginder Singh’s tenure stems from the fact that besides being a hard task master, he has also set a punishing target for himself of putting the CBI on the fast-track and of wrapping up the multi-crore, transcontinental probes within fixed, often unrealistic, deadlines.

He is arguably a man on the move, always on the fax and on the phone but the task before him is a daunting one given the fact that the CBI registers over 1,200 cases a year, a large number of which involve top bureaucrats and politicians. Many CBI officials have begun blaming Joginder Singh for the hastily-prepared indictments that have left many off the hook and say that that while the Director may well contribute to the feeling that the CBI has gone beyond its brief, he may have done it at the cost of a declining conviction rate and of crumbling chargesheets.

The redeeming factors in Joginder Singh’s tumultuous tenure may be the fact that, if anything, he cannot be described as a status-quoist Director. He has shown some signs of autonomy, like the occasion when he announced the names contained in the secret Bofors papers without taking anyone in Government into confidence. Unlike some of his predecessors, he did not believe in playing safe and keeping half-a-dozen people in Government informed about every important decision.

Joginder Singh retires from the post of CBI Director in October this year, but whether he will survive until that date remains a source of much speculation.

And perhaps he can do with some advice from his own treatise, Ways of Success and Happiness in Life, on how to traverse the difficult months ahead.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05