In the summer of 1950, across Madras, copies of the weekly CrossRoads were quietly pulled off shelves — an article on police violence that killed 22 Communists in a Salem prison was deemed too subversive by the State. The Madras government had invoked the Madras Maintenance of Public Order Act to ban the sale and distribution of the magazine in the state.

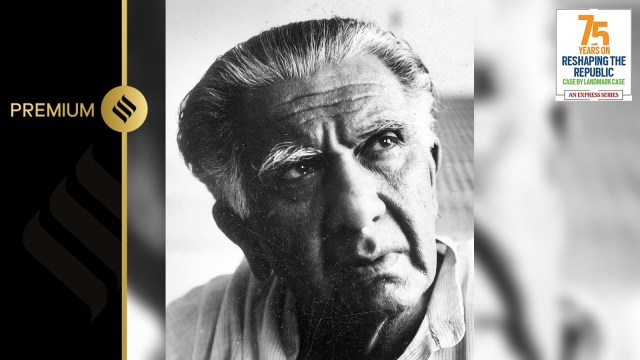

The editor of CrossRoads, Romesh Thapar, moved the Supreme Court, perhaps bullish about the new Constitution that guaranteed a remedy for the enforcement of fundamental rights, including the right to freedom of speech and expression.

His faith in the new Republic and the ideals on which the Constitution was framed wasn’t misplaced. On May 26, 1950, a full bench of the Supreme Court ruled in his favour and Romesh Thapar v State of Madras became the first landmark ruling protecting free speech and limiting arbitrary use of State power. It is, till today, a widely recognised precedent for protection of a free press against State censorship. A crucial aftereffect of the ruling was the First Amendment to the Constitution that placed more limits on free speech.

Five of the six judges of the Supreme Court — who in those days sat together for every case — held the Madras Maintenance of Public Order Act, under which Thapar’s magazine was banned, as “wholly unconstitutional and void”. The court said that unless a law was specifically conceived to address “security of the state”, a general, wide law could not obstruct free speech on such grounds. Justice Fazl Ali was the sole dissenter who said that the law was constitutional.

Born in 1922 in Lahore, Thapar was the son of Lieutenant-General Daya Ram Thapar, CIE, Order of the British Empire, who served as the Director-General of the British Indian Armed Forces Medical Services. Thapar initially worked with The Times of India and was one of only two Indians, along with Frank Moraes, at editorial rank at that time. He then moved to London to set up the India offices of the Free Press Journal, the first Indian news agency abroad, before returning to India, a few months before Independence.

On 29 April, 1949, the month his daughter Malavika was born, Thapar started CrossRoads. The first edition of the weekly had articles by some of the biggest names of the day, including Mulk Raj Anand, Balraj Sahni and Pablo Neruda.

Although Thapar’s association with the Communist Party was well known, along with his weekly dinners at the party’s headquarters at Sandhurst Road in Bombay, the magazine itself had no formal association with the party. It was, however, “strongly anti-Congress”, writes his wife Raj Thapar in her memoir, All These Years.

Story continues below this ad

Raj writes that they had trouble finding a press that was willing to print the weekly and that for the first few editions, they had the pages typeset in one place and then carried them in a taxi to another press to have them printed. Later, it was printed at Jai Gujarat Printing Press, owned by a Communist Party member.

Romesh Thapar handing over the recommendations of the committee to then Union Minister Inder Kumar Gujral. (Express Archives)

Romesh Thapar handing over the recommendations of the committee to then Union Minister Inder Kumar Gujral. (Express Archives)

With its “anti-Congress” and “civil liberties” articles, CrossRoads soon ran into trouble with Congress governments in states.

Months before the Madras ban, the magazine was banned in Bombay, where it was published under the Bombay Public Security Measures Act. Then too, Thapar had moved court. In September 1949, the Bombay High Court took a sympathetic view of his case, with then Chief Justice of the High Court M C Chagla holding that “two views are possible” on the issue — the government’s cross-objections against CrossRoads were “dismissed with costs”.

In her book, Raj notes that the Bombay ban came partly due to the article’s title, ‘Criminal’, which, she says, was given by Thapar’s sister, the historian Romila Thapar, who was then a college student helping her brother. When summoned by the Press Advisory Board, Thapar had refused to tender an apology. “He stood his ground on the right of a journalist to use whatever language he chose,” his wife writes.

Story continues below this ad

However, the ban in Madras, the second for the magazine in five months, pushed Thapar to move the Supreme Court. Thapar’s case was that powers under the Madras Maintenance of Public Order Act to ban his magazine on the grounds of maintaining “public order” were an excessive restriction on the freedom of expression guaranteed under Article 19 of the Constitution. He did not see it merely as an attack on his publication but as a direct assault on India’s fledgling democracy. Well-known Madras-based lawyer C R Pattabhi Raman argued for CrossRoads before the top court.

The six-judge bench that delivered the ruling in Romesh Thapar v State of Madras said, “So long as the possibility of its (the Madras law) being applied for purposes not sanctioned by the Constitution cannot be ruled out, it must be held to be wholly unconstitutional and void.” The court’s view was that while a restriction on free speech is constitutionally sanctioned on the grounds that it impinges on the “security of the state”, public order cannot be construed as a ‘security of the state’ issue.

Romesh Thapar vs State of Madras, 1950

Romesh Thapar vs State of Madras, 1950

Incidentally, Communist ideology found an unlikely comrade that day. On the same day as the Thapar verdict, the Supreme Court delivered a verdict in Brij Bhushan v State of Delhi, over a similar censorship of the Organiser, the mouthpiece of the RSS. It was an article in the magazine on riots in East Pakistan that had led to its ban in Delhi. Veteran lawyer N C Chatterjee, father of former Lok Sabha Speaker Somnath Chatterjee, argued for the RSS. The verdict was short since the judges had given their reasoning in Thapar’s case.

Stung by these verdicts that went against the State’s power to curb free speech, the government eventually amended the law on free speech, leading to The Constitution (First Amendment) Act, 1951, which came into effect on June 18, 1951. Besides other consequential changes to the Constitution — exempting land reforms from scrutiny, providing protections for backward classes, among others — the amendment introduced ‘reasonable restrictions’ on the right to free speech, including “public order”, “incitement to an offence” and “friendly relations with foreign states” as grounds for restricting free speech.

Story continues below this ad

But the underlying reasoning of the Thapar ruling — that laws restricting freedoms must be narrowly tailored for the purpose and that the Supreme Court will guard against arbitrary use of such laws — continue to be relevant.

On the significance of the ruling, former Supreme Court Justice B N Srikrishna told The Indian Express, “If you look at the early days of the Supreme Court, especially in the 50s and 60s, the Supreme Court led the civil liberties movement in India. The Romesh Thapar ruling is from that era, where the court does not grandstand but simply stands guard.”

Thapar’s sister Romila, Professor Emeritus at Jawaharlal Nehru University, said that though her “memories of events at that time are not too clear”, her brother took the “courageous decision to go to court”.

Romesh Thapar with his wife Raj Thapar. (Photo: Facebook)

Romesh Thapar with his wife Raj Thapar. (Photo: Facebook)

“He was naturally upset by the ban… He was happy with the result and, in later years, was particularly pleased that the case had become a precedent for the debate on free speech and a free press. These were for him fundamentally central issues,” she said.

Story continues below this ad

“The ban was imposed in March 1950, a year after the magazine was started and the Supreme Court acted in May that year. The courts worked faster in those days than they do now,” she added.

On the ruling, Raj Thapar writes that the family was “delirious with joy”. However, the case and the pushback from the government took its toll. “Elated revivified, we went back to publishing CrossRoads but the government was a repressive kick,” she writes. Thapar stopped editing the magazine soon after the verdict and subsequently moved from his Malabar Hill flat to Delhi. Eventually, in 1959, he founded the magazine Seminar, which continues to be published by his daughter and her family.

Romesh Thapar handing over the recommendations of the committee to then Union Minister Inder Kumar Gujral. (Express Archives)

Romesh Thapar handing over the recommendations of the committee to then Union Minister Inder Kumar Gujral. (Express Archives) Romesh Thapar vs State of Madras, 1950

Romesh Thapar vs State of Madras, 1950 Romesh Thapar with his wife Raj Thapar. (Photo: Facebook)

Romesh Thapar with his wife Raj Thapar. (Photo: Facebook)