Holi 2017: United colours of spring, and let’s not forget the bhaang and gujiyas

It’s a festival associated with one community but Holi and its cuisine were once owned and embraced by all.

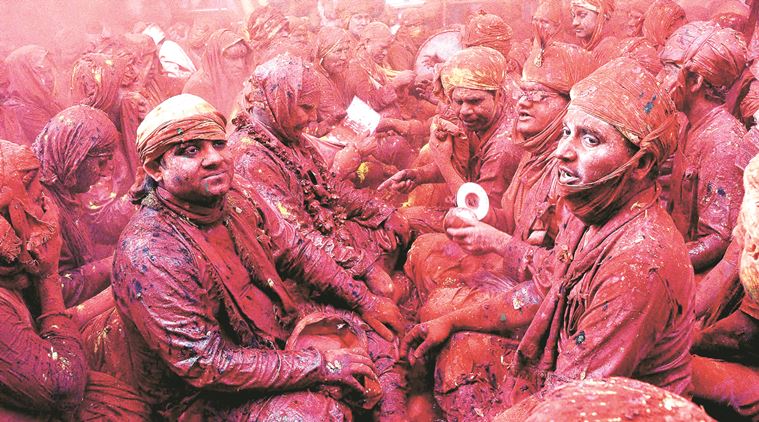

Just the right shade: Holi celebrations in Mathura. (Source: PTI)

Just the right shade: Holi celebrations in Mathura. (Source: PTI)

India’s most colourful festival made an appearance in the recent Uttar Pradesh electoral campaign. Addressing a rally in Fatehpur, Prime Minister Narendra Modi thundered, “If there is electricity during Eid, there should be electricity on Holi too.” The choice of Holi as representing one creed was remarkable, given that this festival once stood for the opposite; the blurring of identity and the melting away of community norms, resulting in vibrant foods, exhilarating drinks and empowering ideas.

Once upon a time in India, Holi didn’t evoke one community’s rejoicing; it stood for the celebration of spring and harvest by all communities. At the heart of Holi is an ancient Hindu legend — the evil Holika, who, while trying to burn her devout nephew Prahlad, is burnt to cinders herself.

But, over time, Holi grew beyond the mythological. “Today’s Holi is associated with one religion,” says historian Rana Safvi, “but once, it was a harvest festival, celebrated by all. In the 17th century, the Punjabi sufi Baba Bulleh Shah joyously wrote, ‘Hori khelungi, keh Bismillah.’ In the 16th century, the Braj poet Ibrahim Raskhan wrote, ‘Aaj hori re Mohan, Hori’; in the 13th century, Amir Khusro composed ‘Khelungi Holi, Khwaja ghar aaye’, celebrating the saint Nizamuddin Auliya.”

Holi was one day of liberty, when the bounds of creed could be overstepped, when — touch being restricted — you could freely touch the one you love. It wasn’t only the seekers; royalty succumbed too. “All the Mughals, save Aurangzeb, enjoyed Holi,” Safvi says. “There are beautiful miniatures of Jehangir playing Holi, called Eid-e-Gulaabi, with Nurjahan. In the Mughal fort, everyone sprinkled Holi colours, even on the emperor, with abandon.”

There was a political point too. Elsewhere, Safvi chronicles how crowds thronged the Holi melas behind the Red Fort. There were tambourines, cymbals and drums playing, nautch girls dancing and mimics imitating the Emperor himself, who indulgently rewarded the impudence.

Russian theorist Mikhail Bakhtin says carnivals in medieval European folk culture “offered a second life outside officialdom…”, a temporary suspension of hierarchy, where mocking authority was tolerated by the powerful, who preferred subjects release resentment in words, not weapons.

On Holi, the ritualistic use of bhaang or cannabis heightened such sensuousness and senselessness. Theorist Walter Benjamin described its sharp stupor where “the threshold between waking and sleeping was worn away, as if by the to-ing and fro-ing of streams of images.” Holi’s “streams of images” were too beguiling to resist. Safvi says, “In the 19th century, Bahadur Shah Zafar and Wajid Ali Shah were writing gorgeous Holi poetry.” Their poetry captured aching jiyas, teasing piyas, the sensuousness of soaked cholis, the sadness of souls yearning to be drenched in love.

But the times changed; the Revolt of 1857 and the brutal crushing of a syncretic Hindustani nobility curbed Holi’s appeal. The festival’s abandon was seen as a dissolute weakness that led to the vanquishing of a martial empire. The dhols and dols, swirling colours and beating hearts, were closed off to many and it slowly became circumscribed to a festival of Hindus.

But the food was impossible to limit.

Beetroot tikki chaat.

Beetroot tikki chaat.

The heart of Holi food is the gujiya, a sweetmeat of harvest wheat, filled with nuts and dried fruit, an agrarian expression of the earth’s goodness; but the little gujiya was a traveller. The sweetmeat is a twin of the shekerbura of Azerbaijan, which, like its Kumbh Mela-sibling, is a crescent-shaped pie, its skin of delicate, wheaten pastry — representing the moon — stuffed with almonds and sugar. In India, the shekerbura’s doppelganger is stroked with fragrant rosewater, a typically Persian touch. Chef Anahita Dhondy of SodaBottleOpenerWala says, “Gujarati Parsis play Holi. They brought several Persian cooking methods to India; they even innovated on the gujiya. They created copra khaman, which is a big gujiya, the size of your hand, stuffed with sweetened coconut, taking an originally Persian dish, adding local produce.”

Holi doesn’t limit itself to the sweet though; the dishes of the season arch beautifully into the spicy and tart, an array that heightens senses. For instance, Holi features chilli-hot chaats, originating from Varanasi, but given a new twist in Mughal Delhi. “One of Babur’s disappointments with India was that there was no decent fruit,” writes historian Lizzie Collingham in Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors. But Babur didn’t sink into melancholia over missing melons. “He discovered it was possible to cultivate sweet grapes in India…Akbar set up an imperial fruitery, staffed with horticulturalists from central Asia…Jahangir and Shahjahan took particular delight in having fruit weighed…This obsession was more than mere gluttony,” notes Collingham. “The delicate flavour of a Persian melon, the sweetness of a Samarkand apple…the introduction of these fruits into India were exquisite reminders of the central Asian civilisation they bequeathed…”

With the cheeky flourish of the Indian cook, the glorious gift was made tangier in a Holi chaat, a mishmash where each fruit could be tasted distinctly among a mixed whole, retaining its original flavour, its texture, but also blending into a hectic blur.

Gata, an Armenian dessert inspired by the gujiya.

Gata, an Armenian dessert inspired by the gujiya.

Tastes changed as you travelled farther. Chef Saransh Goila of Goila Butter Chicken describes Maharashtra’s karanji gujiya, which is stuffed with jaggery, sesame and coconut, and is richer than its north Indian cousin. “Holi’s harvest is also celebrated with kanji, which is a really tart mustard-fermented water, paired with moong or urad daal pakodi. In Mumbai, we do a beetroot tikki chaat, a rich purple tikki with a white snowpea chaat,” he says. Goila has travelled across India, researching its culinary diversity, and adds, “On Holi, in Jharkhand, I found a poori called bhuska; it’s not made of flour or wheat, but rice and chana dal, special to the harvest there.”

Holi dishes, following local harvests, multiply; there are diverse Holi malpuas, pancakes fried in ghee, dipped in syrup, soft or crunchy as you like. Chef Megha Kohli of Lavaash by Saby says, “In north India, malpua is made with maida, in Odisha, with smashed banana, in Bengal, with semolina. For me, though, gujiya is the iconic Holi dish. I grew up making Holi gujiyas with my dadi. Today, inspired by gujiyas, I’ve created an Armenian dessert called gata. It is puff pastry, stuffed with sweetened homemade cheese. This chhena is an Armenian touch — but it’s also typically Bengali.”

Which came first? Did the Armenians, travelling to India as merchants, wanderers, philosophers, priests, bestow us chhena? Or, did the Bengalis, who mark Holi with vibrant singing, celebrating the great Krishna devotee Chaitanya, gift it to the Armenians? Evoking the melting colours of Holi, there is no distinct way of knowing who gifted whom; Holi simply symbolises the shared hopes of humanity, to be celebrated together, not apart.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05