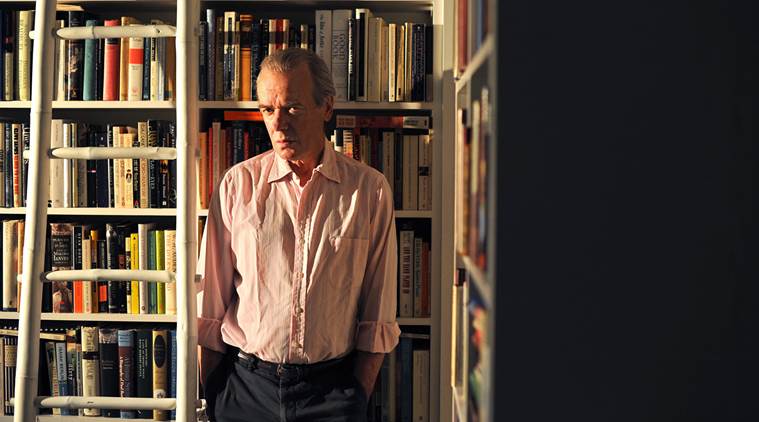

You have to write when you’re young, stupid and brave: Martin Amis

British novelist Martin Amis on writing, living in Trump’s America and the tricky business of being a writer’s son.

The things we have handed down: Martin Amis.

The things we have handed down: Martin Amis.

Martin Amis, once hailed by The Guardian as “Britain’s greatest living writer”, does not live in England anymore; in 2011, the 67-year-old novelist and his wife moved across the pond. Amis spent almost all his sessions at the recently-concluded Tata Literature Live! Festival in Mumbai, discussing what a post-Brexit and post-Trump world has in store for us. But over lunch, he is also happy to talk about other issues. Excerpts from a conversation:

When you moved to America, you’d said in an interview that Americans should be thankful that they live there. What would you say now?

I was excited to be there, even though I was intimidated by the size of America. Henry James had said that it’s more of a world than a country, and I think that’s a good starting point to think about America. Everything there is large, their novels, too (laughs).

I’d moved to America so that my wife and I could be close to her mother and stepfather. The other reason was Christopher Hitchens, my best friend, who died not long after I’d got there; I thought he would live as long as he was meant to, that he would beat the cancer. He died six months after I reached.

I was in London for Brexit and in New York for (Donald) Trump, and I watched the election results with growing incredulity. A popular German historian, whose name I can’t recall, said that the main feeling after Hitler was elected chancellor was not of horror, but unreality. It’s not comparable, but that’s how I felt, too. You go out and the street looks the same, the statues are still there, the leaves on the trees still waving, just as the day before. But it’s a different country. Both events have been motivated by a xenophobic outlook and a nostalgia for a largely imaginary, vanished England/America. In the Brexit business, there was a fear of refugees, but there’s no refugee invasion in America yet. America is an immigrant society — Trump’s grandfather was an immigrant, his wife Melania is an immigrant!

Would you say that the American liberals and the media were living in a bubble and didn’t recognise Trump’s appeal enough?

This is the grounds for applying what I call the ‘Barry Manilow Law’. This was formulated by the British-Australian journalist, Clive James, and I find it very useful in times like these. He says, ‘Everyone you know thinks Barry Manilow is terrible. But everyone you don’t know thinks he’s great’. Now, everyone I know is a Democrat, everyone I don’t know is a Republican. Everyone I know thinks Trump is an obvious charlatan and monster, but everyone I don’t know thinks he’s wonderful. Is it a bubble or is it a vanguard? I like to think liberalism is the vanguard value. Would Trump have won if he were not famous and looked like he looks? If you saw him 100 yards away in a human gathering, you’d think, ‘I’m not going near that.’ He’s immediately identifiable as a brute, a lout, a wretch, a conman and shyster.

The media are now talking about ‘The Sleep of Reason’, that seems to have overcome societies, as if reason actually gets tired and needs a long nap, and has to curl up and recuperate. This was talked about in the years leading up to World War I, too. If you read the writings of Hitler and Lenin, reason was never mentioned without an insulting adjective like ‘cowardly’, ‘flimsy’, ‘inadequate’. It’s tremendously liberating to throw off reason for a while, because, suddenly, anything seems possible. And that’s what Trump’s campaign did — it uninhibited a certain kind of American voter, allowing them to revolt against political correctness. In the last few months, I’ve been thinking how much we have to be thankful to political correctness. Those things that we might say in a slack moment, we realise are unspeakable. But with Trump in power, one can say them again.

You’ve written two novels, Time’s Arrow (1991) and Zone of Interest (2014), set during the Holocaust. What do you make of the racial hatred in post-Trump America?

The great wound in American history and consciousness is slavery — two-and-a-half centuries of it, and a civil war where 6,50,000 Americans were killed by other Americans. After the civil war, a whole century of segregation, Jim Crow, then the civil rights movement — and that’s only 50 years ago. Those things don’t disappear with the snap of a finger. And then you have a Black president — not a machine politician — but an evolved man, graceful and elegant. For a certain sort of white, working class, non-educated male, that’s been very hard to take. There’s a man down in the hog wallow of Tennessee, looking out of his truck and thinking (imitates Southern drawl), ‘I may not be much, but I sure am better than any Black man’.

When you began writing, your father, Kingsley Amis, didn’t encourage you at all. He famously threw your most-lauded work, Money: A Suicide Note (1984), across the room. What about your children? Have they read your work?

When a writer-parent encourages their child to be a writer, it’s tremendously egotistical; it’s a way of saying to the child, ‘You can be me. I’m so marvellous that, obviously, you want to be me’. It’s much better to do as my father did, which is to ignore me. He did like my first novel, The Rachel Papers (1973), and he wrote me a little note saying so.

My eldest son has written a novel and I’d be delighted to read it when it’s in proof, but I don’t want to read it before, because then I’ll want to make suggestions and it gets complicated. My 20-year-old daughter read my first novel last year, which is narrated by a 19-year-old, and she said she loved it, and quoted the best paragraph in the novel in a letter to me, which was about being 19.

How did you feel about following in your father’s footsteps all those years ago?

Some unsympathetic people say that it must have been very easy for me to have become a writer, because my father was one. I didn’t know how rare it was until I looked into it just a year or two ago. I’ve had conversations with Dmitri Nabokov and Adam Bellow and they both had novels in their minds that they were wondering what to do with. Dimitri was 40 at the time and Adam was 30. You have to do it when you’re young and stupid and brave, otherwise doubt and self-consciousness creeps in. I think writers usually come out of nowhere — they’re usually the children of school masters, tradespeople, or coal miners. But I didn’t come from nowhere and I don’t see what I’m meant to do about it.

You’ve spoken about the ‘throb’, that moment when the idea of a novel comes to you.

That’s Vladimir Nabokov’s word, and John Updike called it a ‘shiver’. It’s a recognition from the unconscious, like a telegram from your unconscious. Sometimes, when you get this throb, you think about it for a few weeks and then you start. And sometimes, it’s as if the novel is already there and all you have to do is get into shape.

Someone who has written about this, rather surprisingly in a good way, is Norman Mailer. He wrote a book called The Spooky Art (2003), about fiction; full of insights about where novels come from, the role of the subconscious, how it connects with your dream life. I used to talk to my father about it and we agreed that sometimes, you come to a sort of critical point in a novel, and you need a character to appear who is going to ease the plot. And as you are wondering about creating such a character, more often than not, you look back, and that character is already there. This completely rescued a novel of mine, House of Meetings (2006), that I was having so much trouble with.

You’ve visited India a few times now. Have you felt even the slightest throb or shiver about anything you’ve seen or encountered?

No. But I have to say your tourist board got it right, when they said ‘Incredible India!’ I felt this particularly in Jaipur, a few years ago, when I was there for the lit fest (Jaipur Literature Festival). In the street, there’s a painted elephant waddling past in one direction, and a herd of goats coming from another direction against the traffic. It’s that atmosphere where you think that it’s on the absolute brink of utter anarchy and riot, but it never happens. Just looking at the street scene in Jaipur, I thought, no wonder Indian English literature is so magically realist, because reality here is so magical.

So, which Indian authors have you read?

Salman Rushdie, the Naipauls — Vidia and Shiva. Shiva was Vidia’s younger half-brother and he wrote a marvellous first novel called Fireflies, a very gentle, funny and touching work. But he died very young — heart attack. I like Rohinton Mistry and Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy — it’s very long but pretty gripping, I thought.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05