The Word Became Flesh

A translation of Ashok Vajpeyi’s poems reveals his faith and an awareness of his failures.

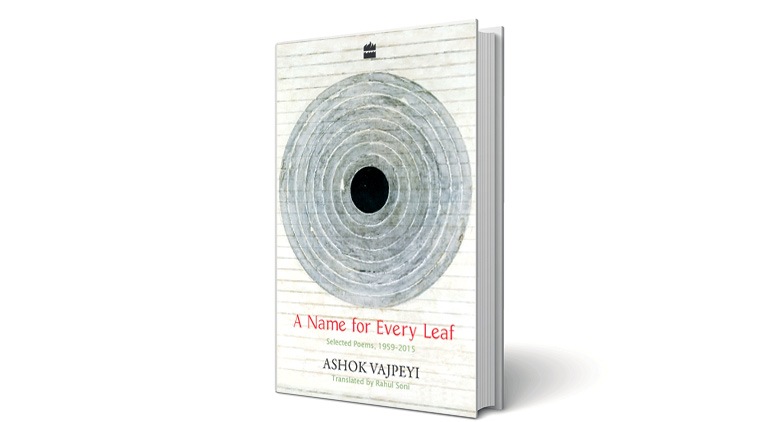

A Name for Every Leaf Selected Poems, 1959-2015

A Name for Every Leaf Selected Poems, 1959-2015

Book: A Name for Every Leaf Selected Poems, 1959-2015

Author: Ashok Vajpeyi

Translated by: Rahul Soni

Publisher: Harper Perennial

Pages: 228

Price: Rs 450

Plato is responsible for perhaps the most passionate assault on art and poetry in human civilization. To disparage the tribe, the Greek master even put up a supposed poet, Meletus, in The Apology as one of the three prosecutors of Socrates. If all art is indeed an aspiration to confront both its ancestors and posterity, Ashok Vajpeyi is among the biggest custodians of what can be termed as the “cosmos of arts” in Indian languages. He has 15 poetry collections in Hindi, nearly a dozen of which were written in the last two decades, besides substantial work on music and visual arts in English.

A Name for Every Leaf, an English translation of a selection of his poems written between 1959 and 2015 by Rahul Soni, also has his essays and an interview on the art of poetry, which makes this a poetic manifesto of sorts.

A poet is marked by the universe he weaves into his verses. Besides love, the perennial theme of poetry, Vajpeyi is on a search for ancestors and gods, fusing a neighborhood with distant galaxies, with an epistemic faith that “hope” resides in words alone. Most gods have disappeared, the rest are fallen creatures like humans and the poet chooses “holy words” not for a “prayer”, but to compose poems.

“I am most human”, he asserts, “when I am with poetry”, and elsewhere acknowledges the eternal vigil of words: “words watch over us: They fall weightless upon the soul.”

Does Vajpeyi embrace poetry by Neti-Neti, after navigating other available universes? It appears that his faith in poetry has an epiphanic, intuitive element. It goes before the civilisation learned about the word faith. In this unflinching fidelity to poetry also lies his tribute to his ancestors, notably Ajneya, for whom the word was the supreme entity.

Indian languages have an ingrained mythical consciousness that cannot be easily rendered into English, often not without the considerable loss of the accompanying fable. Rabindranath Tagore’s Gora or UR Ananthamurthy’s Samskara, two novels that grapple with the idea of India, lose much of their textual conflict in English. The word is not an isolated entity. Being perhaps the most definitive arena of cultural friction and fusion, the word evolves over centuries, bearing the bruises and wounds inflicted by its users.

Translating poetry, whose objective as Vajpeyi notes is to “retain, reanimate and rehabilitate racial memory”, is fraught with obvious dangers. This is the second book-length poetry translation by Soni after Srikant Verma’s Magadh. In a quiet linguistic transformation Soni brings to Vajpeyi’s verses, one can hear the silent conversation between a veteran poet and a young translator. “Earlier I translated like a writer. I translated as if these were my poems and I wrote them in a different language. It’s now that I translate as a translator.” In Soni’s observations about his craft lie the struggle of a translator who evolves with the language he weaves.

This book ends with Vajpeyi’s lecture, “Failure of poetry”, at the Poetry Society of India two years ago. Approaching his 75th year, Vajpeyi reflects on the many failures he, as a poet and as an institution-builder, underwent. He laments the diminishing role of poetry, almost wails that “poetry has lost the epic impulse” and “is no longer able to cope with the world now dominated by poverty and exploitation or opulence in plenitude, fashion, glamour”.

The aging poet is now able to discern the limitation of poetry and notes that poets “seem to be living in a ghetto of our making. There is a poetry ghetto in which we are now caught”. Read this wonderful essay as his swansong, to learn about the intellectual and devotional contours of a poetic life. To learn that while the poet admits to his “failure” at the dawn, but the final breath of his art lends a “moral dignity” to this failure. Vajpeyi creates a sacred anatomy in which the poet “laments only in poetry because there is no other space left for regret or dreams”.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05