The biggest science awards go to… the men

Since 1958, only 20 of the 592 Bhatnagar prizes – among the most prestigious science awards in India – have gone to women scientists. Why the glass ceiling is so hard to punch through

Rohini Godbole of IISc, Bengaluru, says the loss of career years for women can be made up by considering their “academic age” instead of biological age to determine qualifying cut-offs for awards and fellowships. (Special Arrangement)

Rohini Godbole of IISc, Bengaluru, says the loss of career years for women can be made up by considering their “academic age” instead of biological age to determine qualifying cut-offs for awards and fellowships. (Special Arrangement) When the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar (SSB) awards for 2022 were announced in New Delhi on September 11 this year, recognising 12 of India’s “exceptional” young scientists under the age of 45, there was one noticeable let-down.

Like in 2021, there were no women among the award winners.

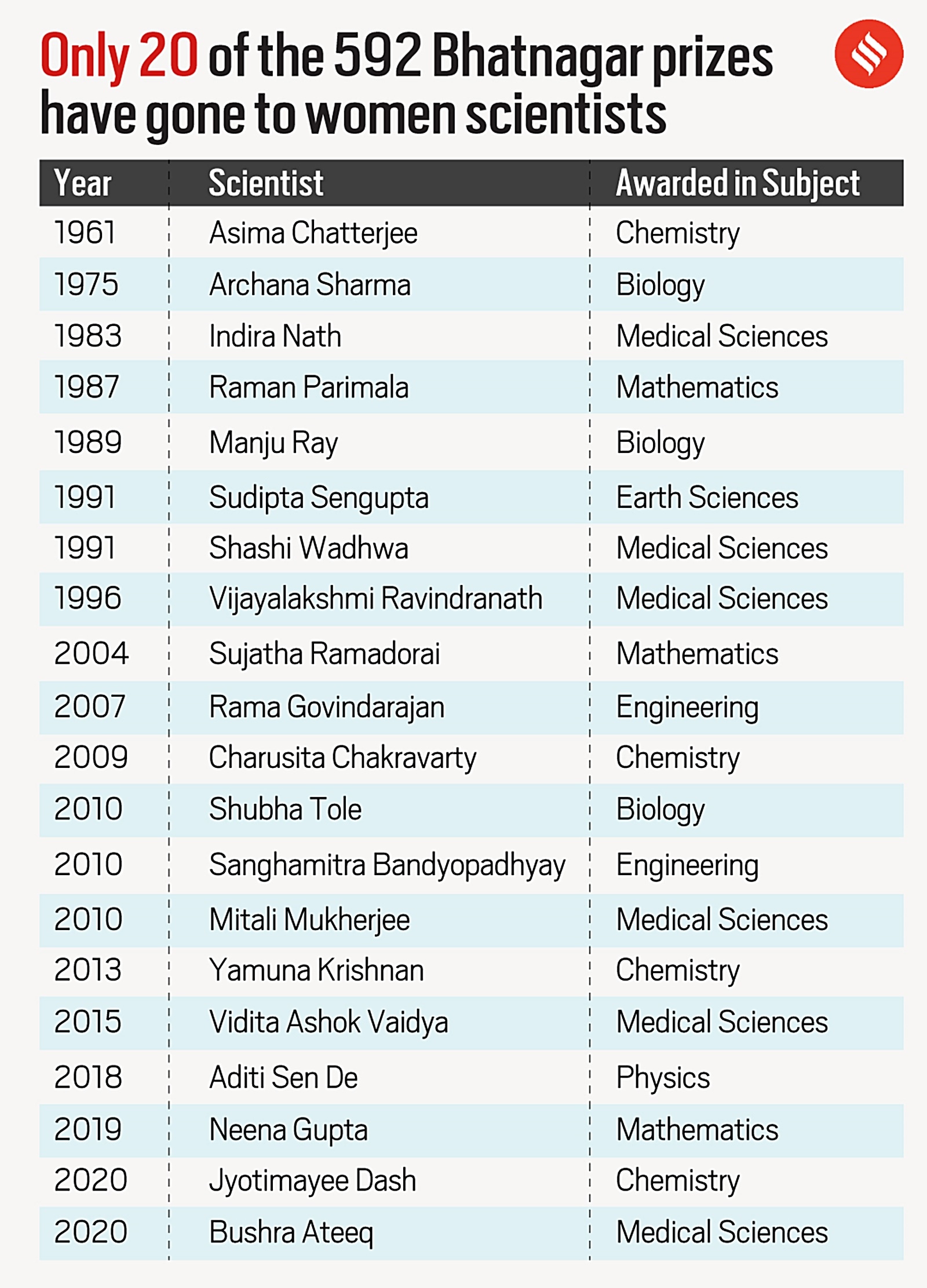

In fact, since the awards were first given out in 1958 by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and over six decades since Asima Chatterjee became the first woman to win the coveted prize, only 20 of the 592 Bhatnagar prizes have gone to women scientists.

The absence of women awardees is particularly jarring since the annual Bhatnagar awards cover seven scientific disciplines: biology, chemistry, mathematics, physics, medicine, engineering, and earth, atmosphere, ocean and planetary sciences – part of the larger STEM disciplines where women have increasingly made their presence felt.

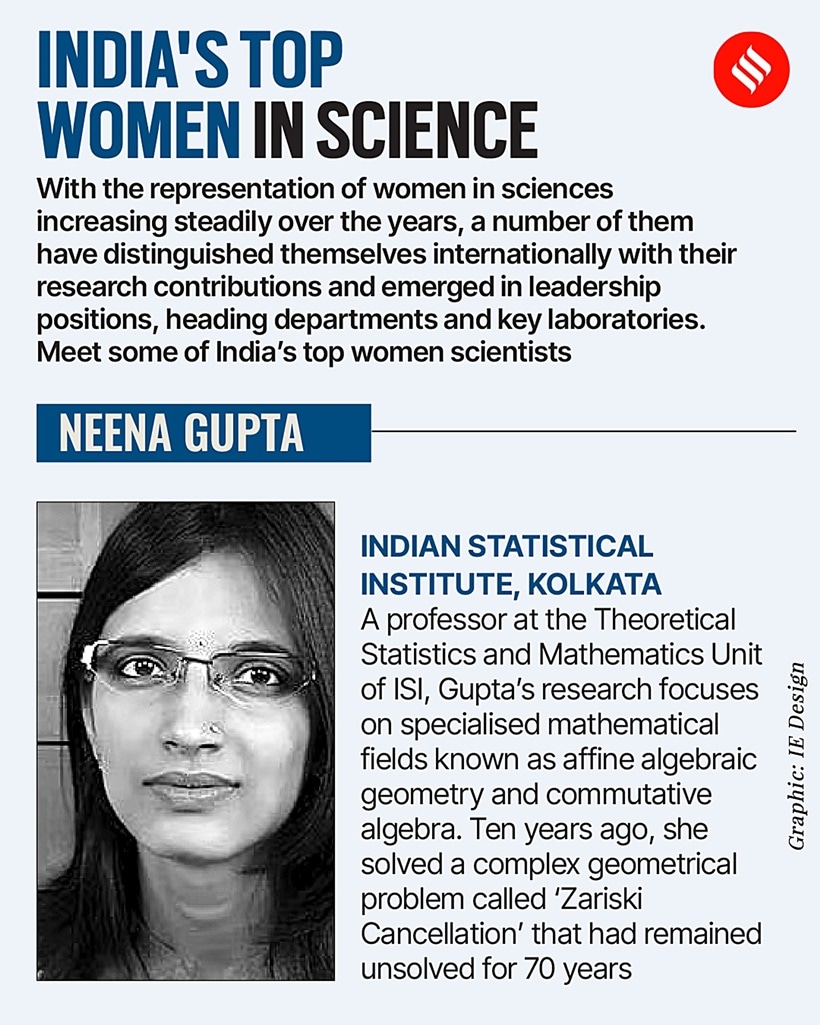

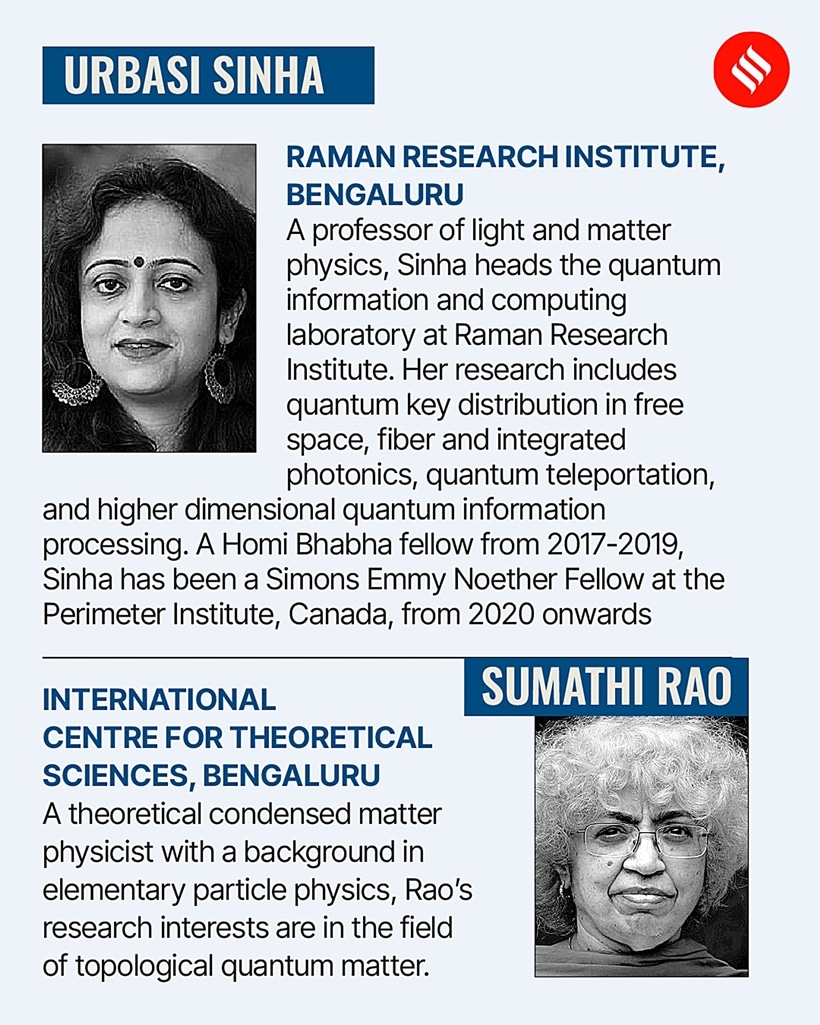

Leading from the front

Leading from the front

In April last year, in a written reply to a question in Rajya Sabha, Union Minister of State (Independent Charge) for Science & Technology Jitendra Singh said the percentage of women in R&D is 16.6% of the total number of scientists working in science and technology organisations.

That number is set to go up with more girls taking up STEM subjects in colleges. According to the latest All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) report, more girls (53.1%) than boys enrolled in science courses in 2020-21, up from 51.7% in 2019-20. Of those who enrolled in sciences courses at the undergraduate level, 52% were women; at the PG level, that stood at 61.3%.

Despite these encouraging numbers, for women in science, awards and recognition at the highest levels are an uphill climb. Some of India’s top women scientists say it’s time the ground evened out.

Rohini Godbole, physicist, Padma Shri recipient and professor at the Centre for High Energy Physics at the Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru, points out that the underrepresentation of women awardees doesn’t add up.

“The most obvious reason for the small number of women awardees would be that there are very few women practising science at the cutting-edge level – about 15-25% of the total. However, the fraction of women winning awards and recognition at the highest level is not even commensurate with that small fraction of women in science. For example, since the inception of the SSB awards, in the Physical Sciences category, there has only been one woman awardee (Aditi De, 2018) whereas at least over the past 20-30 years, the fraction of women doing research in physics in India has been a healthy 10-15%. Similar statements can be made, with similar force, for subjects like Biological Sciences and Chemical Sciences – traditionally considered to be favoured by women scientists,” says Prof Godbole, suggesting that CSIR should analyse the underrepresentation of women by making available gender data for the past 20-25 years on nominations, age of nominees, and gender composition among committee members and referees/experts.

According to the official website of the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar prize, names of potential award winners can be proposed by a member of the CSIR governing body; vice chancellors of Indian universities; directors of IITs; Directors General of major R&D organisations such as DRDO, ICMR, ICAR IMD; directors of CSIR laboratories and institutes; secretaries of the government science departments member in-charge (Science) in the NITI Aayog; and former Bhatnagar Prize awardees, among others.

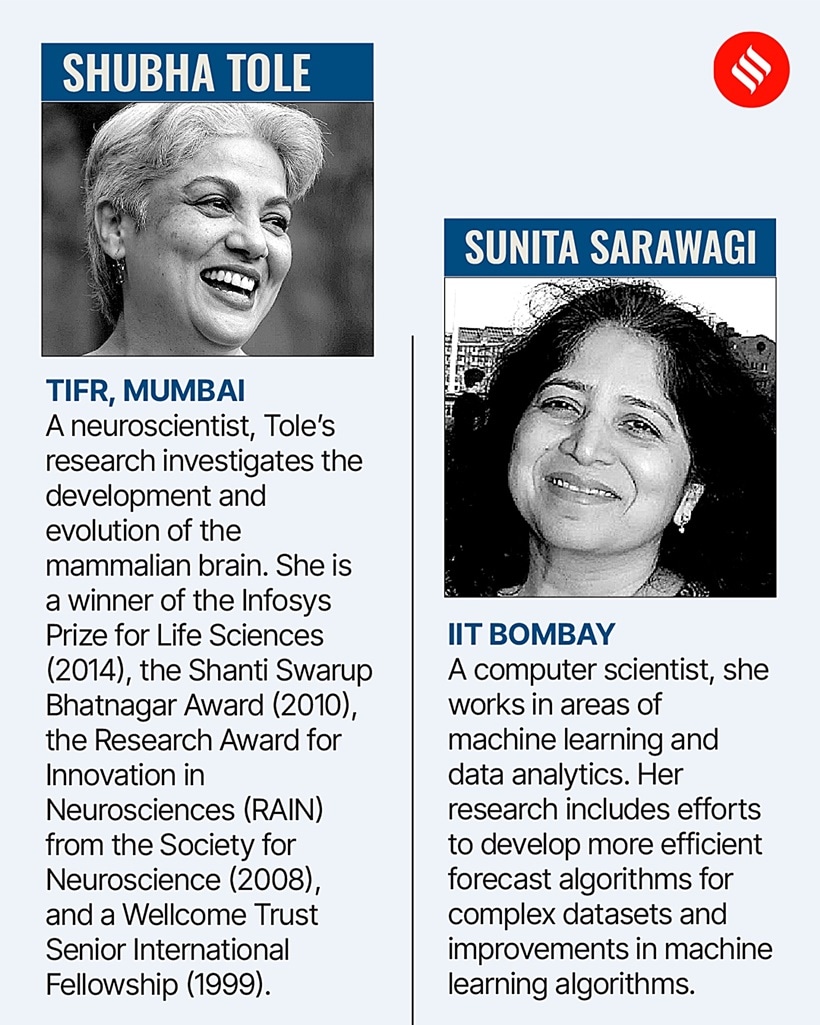

Speaking to The Indian Express, Dr Shubha Tole, neuroscientist, senior professor and Dean of Graduate Studies at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), says those who nominate candidates for awards must first attend sensitisation programmes before their nominations can be accepted.

Dr Shubha Tole of TIFR says those nominating candidates for awards must first attend sensitisation programmes before their nominations can be accepted. (Special Arrangement)

Dr Shubha Tole of TIFR says those nominating candidates for awards must first attend sensitisation programmes before their nominations can be accepted. (Special Arrangement)

“Such programmes should be aimed at sensitising people to recognise that qualities that are associated with a successful career – creativity, novel research directions, leadership – may work differently in the case of women as opposed to men. Those nominating must learn to recognise that women may not ‘sell’ their work as confidently or prominently in conferences as their male counterparts, that negative social perceptions of women who speak up, or have opinions different from those around them, also colour the perception of their leadership qualities. All these factors possibly play a part in why people nominate fewer women candidates,” says Dr Tole, who has chaired the Women in Science panel of the Indian Academy of Sciences and is a winner of the Bhatnagar award in 2010 for her “fundamental contributions to our understanding of brain development…”

CSIR Director General N Kalaiselvi is, however, hopeful of change. “It is not just about there being few women SSB awardees. As we know, the ratio of women to men is lower in many areas, especially in scientific research. However, the situation in recent years is changing for the better. I am sure that in the years to come, with more women taking to science, there will be many more women receiving awards and accolades. There have been more women in leadership positions in CSIR in the last five to seven years than perhaps in the entire history of CSIR taken together before that.”

Dr Shekhar Mande, who was CSIR-DG from October 2018 to April 2022, is categorical that the selection process for the Bhatnagar awards is transparent. “There are seven disciplines and a senior scientist is appointed as chair of each of these disciplines. When I was CSIR-DG, I made sure that there were at least two women (chairs). There would be approximately 10 members (in each of the seven disciplines) with a fair representation of women members… As CSIR-DG, I would interact with the seven chairpersons before the meeting to ensure equal opportunities on the basis of geography, gender, university/labs, and so on… There are no external criteria except for merit,” Dr Mande told The Indian Express.

He adds that during his tenure, there were efforts to encourage leadership among women. “There were 37 CSIR labs and not a single one was headed by a woman. During my tenure, we made sure that seven highly qualified women were appointed as head of CSIR labs.”

Time to rethink age cutoff?

Dr Vineeta Bal, Professor Emeritus, Biology, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Pune, calls the upper age-limit – 45 in the case of the Bhatnagar awards – to qualify for awards “problematic”.

“Often, women cannot wait until 45 to become mothers, thus leading to active breaks and/or periods of suboptimal work that hinder their achievements. Mothers do not like to claim that they had difficult years while the child/children grew up, but factors such as these do need to be included in the selection process to compensate for the underprivileged status of women and other groups,” she says.

(L) Dr Vineeta Bal, Professor Emeritus, Biology, IISER Pune, says the age limit of 45 can be “problematic” for women scientists. (R) Debjani Paul of IIT Bombay says, “When I take short breaks, I switch off my work mode and focus on recharging.” (Special Arrangement)

(L) Dr Vineeta Bal, Professor Emeritus, Biology, IISER Pune, says the age limit of 45 can be “problematic” for women scientists. (R) Debjani Paul of IIT Bombay says, “When I take short breaks, I switch off my work mode and focus on recharging.” (Special Arrangement)

Dr Tole points out that while it is often thought that child-bearing and child-rearing years are generally associated with low productivity and that women need special allowances for this, she says these need not be treated as “problems of women; rather they need to be framed as problems of institutions and spouses that fail to support women students, postdocs and faculty so that their productivity is minimally affected. Raising children is a decades-long job. Parent-friendly policies will help all parents, not just women”.

Dr Godbole suggests that the loss of career years for women can be made up by either increasing the age limit and/or considering the “academic age” – years spent after setting up one’s lab, for example – for women instead of their biological age to determine cut-offs.

“This latter measure can even be implemented in a gender-neutral fashion and can apply to men who take time off from a science career for some reason and rejoin later. I hope that this can be introduced at least now for the new avatar of the Bhatnagar Awards, the Vigyan Yuva-Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar,” Prof Godbole says.

Debjani Paul, Professor, Department of Biosciences and Bioengineering at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, suggests that instead of proposing an age limit for awards, committees can specify the number of years that a nominee needs to have spent as an independent principal investigator and consider the candidate’s achievements in that period.

Considering the academic age of candidates is one of the recommendations in the Equity and Inclusion chapter of the Science, Technology and Innovation Policy 2020. “Ageism-related issues and minimisation of career breaks are to be addressed for effective retention of trained women into the STI (Science, Technology & Innovation) workforce. In the case of professional career milestones such as recruitment, awards and funding schemes, age cut-offs will be implemented considering academic age rather than biological/physical age,” states the policy document.

On its part, the government has come up with a string of measures to correct the gender skew – from a Standing Committee constituted in 2016 “to identify and correct any imbalances” that hinder women in science and technology; the GATI (Gender Advancement for Transforming Institutions) programme to “create an enabling environment for equal participation of women” in STEM disciplines; and the ‘National Award for Woman Scientist’ instituted by the Ministry of Earth Sciences since 2018.

CSIR also gives a five-year relaxation in the upper age-limit to women candidates to be eligible for award of fellowships and associateships to pursue doctoral and postdoctoral research.

In a written response to The Indian Express, CSIR-DG Kalaiselvi said, “Recently, aligned with the Government of India’s initiative to empower women and promote ‘Nari Shakti’ in the country… CSIR, for the first time, announced a Special Call for Research Grants for Women Scientists (CSIR-ASPIRE). In this, only women scientists across the country are eligible to apply for research grants to carry out R&D in major disciplines of science and engineering. We have initiated the process of evaluating the grant proposals received under the scheme.”

Forever a tight-rope balance

One of India’s most accomplished mathematicians and science educators, the late Mangala Narlikar, while reflecting on her career, “lack of ambition” and her life with her husband, the celebrated astrophysicist Jayant Narlikar, once wrote, “Fortunately, my husband… respected my wish to study mathematics although he too did not wish me to prioritise career over family.”

While in Cambridge with her husband, where Jayant made a name for himself globally, Mangala attended a few graduate lecture courses and supervised some undergraduate students, but full-time research remained difficult with the birth of two daughters.

“My story is perhaps a representation of the lives of many women of my generation who are well educated but always put household responsibilities before their personal careers,” she wrote.

Bhatnagar prizes awarded to women scientists

Bhatnagar prizes awarded to women scientists

Some of India’s top women scientists will tell you not much has changed since then with most of them slipping into familiar roles once they get home – as the primary caregiver shouldering responsibilities of children and the elderly.

Prof Godbole, who was conferred with the Ordre National du Merite, one of the highest distinctions granted by France, says her “scheduling discipline” came in handy. “I recall the words of an older colleague, Prof Preeti Shankar. She used to say since I know I have to leave the workplace at 5 pm and that it is a hard cutoff, I have trained myself to minimise the time for coffee breaks,” she says.

Dr Tole says juggling work-life dynamics is always “complicated”, but the flexibility her career offered came in handy. “Research is not typically a 9-to-5 job. One can run experiments/ write papers/see students’ data and write feedback at one’s own convenience. In India, scientists often live on or near the research campus. Parents can manage parent-teacher meetings, mid-day school closings etc more easily than in corporate jobs. Infant care, too, is easier. I would breastfeed my son and return to work. Or, if I had to wake up for a midnight feeding session, I would use that period of sleep disruption to write emails to students or to foreign collaborators who would see it during their working day. It all worked out,” Dr Tole says.

Dr Debjani Paul, whose research interests are on microfluidic devices for bioengineering and health care applications, says that she struck a balance by choosing what to work on. “While there would be frequent periods when my work would get all my focus, when I take short breaks, I switch off my work mode and focus on recharging,” she says.