In Chargheri, the last village on the south-eastern side of the Indian Sunderbans, Anushka Rai, 3, stands on the steps of her school, Purbasha Rural Child Education Centre, and recites a poem by a little-known Bangladeshi poet.

The one-room school is singularly positioned — it stands on land that is battered by back-to-back cyclones. On the other side of the Garal river that flows past the village is the famous tiger territory of Sunderbans.

Anushka’s poem is about nature. “Khoob shundor (Bangla for ‘very beautiful’),” says Umashankar Mandal, 45, founder of Purbasha. The only teacher in the school, Shampa Paik, gets down to implementing the school’s itinerary for the day, where the students, all under six, have 30-minute classes each in Bangla, English and Math, followed by poetry, storytelling and art on nature in the Sunderbans.

The Purbasha primary school, set up by Umashankar as part of that conservation plan, has 80 students, the children of the Mangrove Army. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

The Purbasha primary school, set up by Umashankar as part of that conservation plan, has 80 students, the children of the Mangrove Army. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Starting November 30, as 193 UN member countries get together in Dubai for the 28th Conference of Parties climate summit to discuss the seemingly intractable problem of climate change, away from the grand declarations and geopolitical wranglings, here in the Sunderbans, one of the most ecologically threatened regions, is a unique community-led model that offers the way forward.

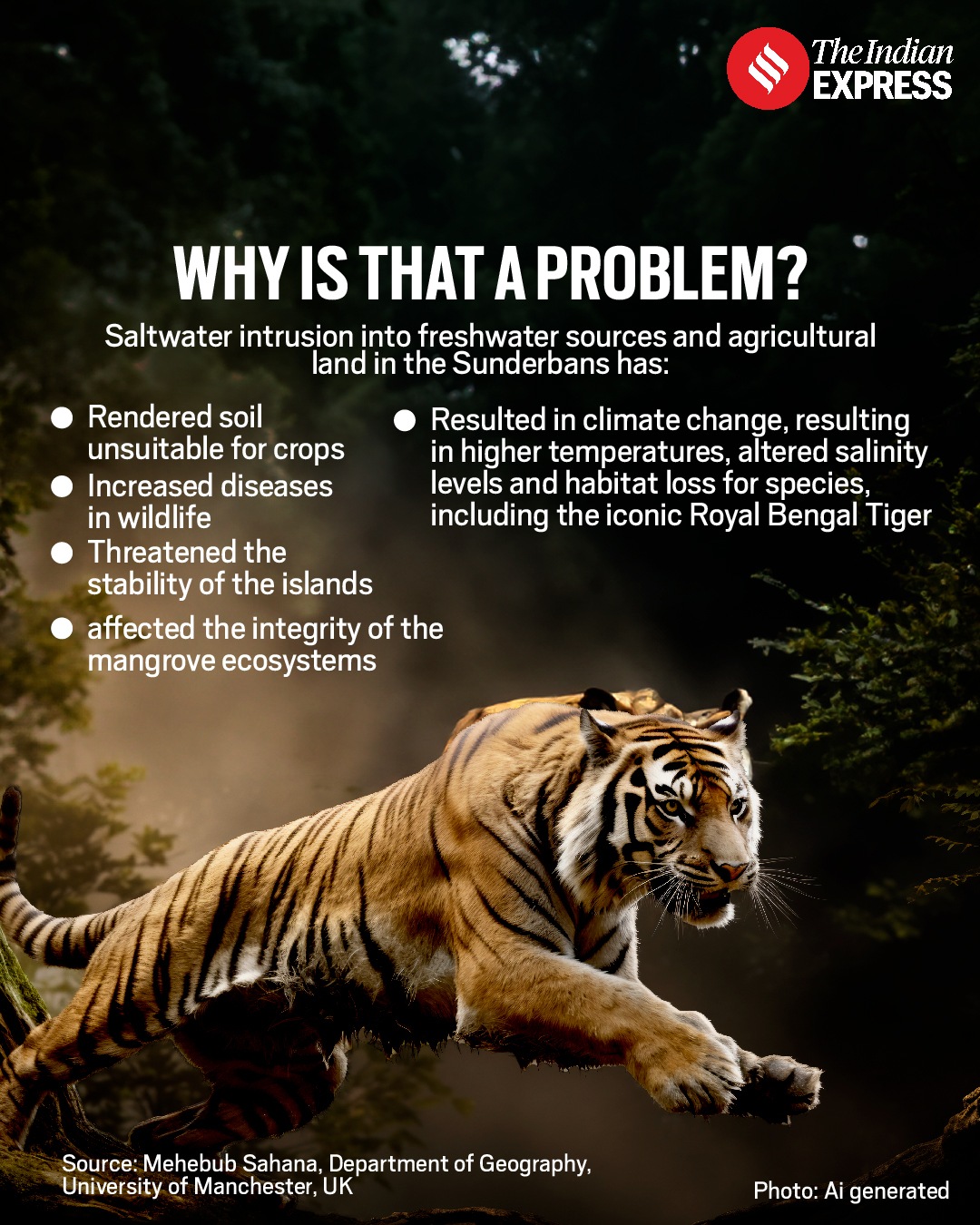

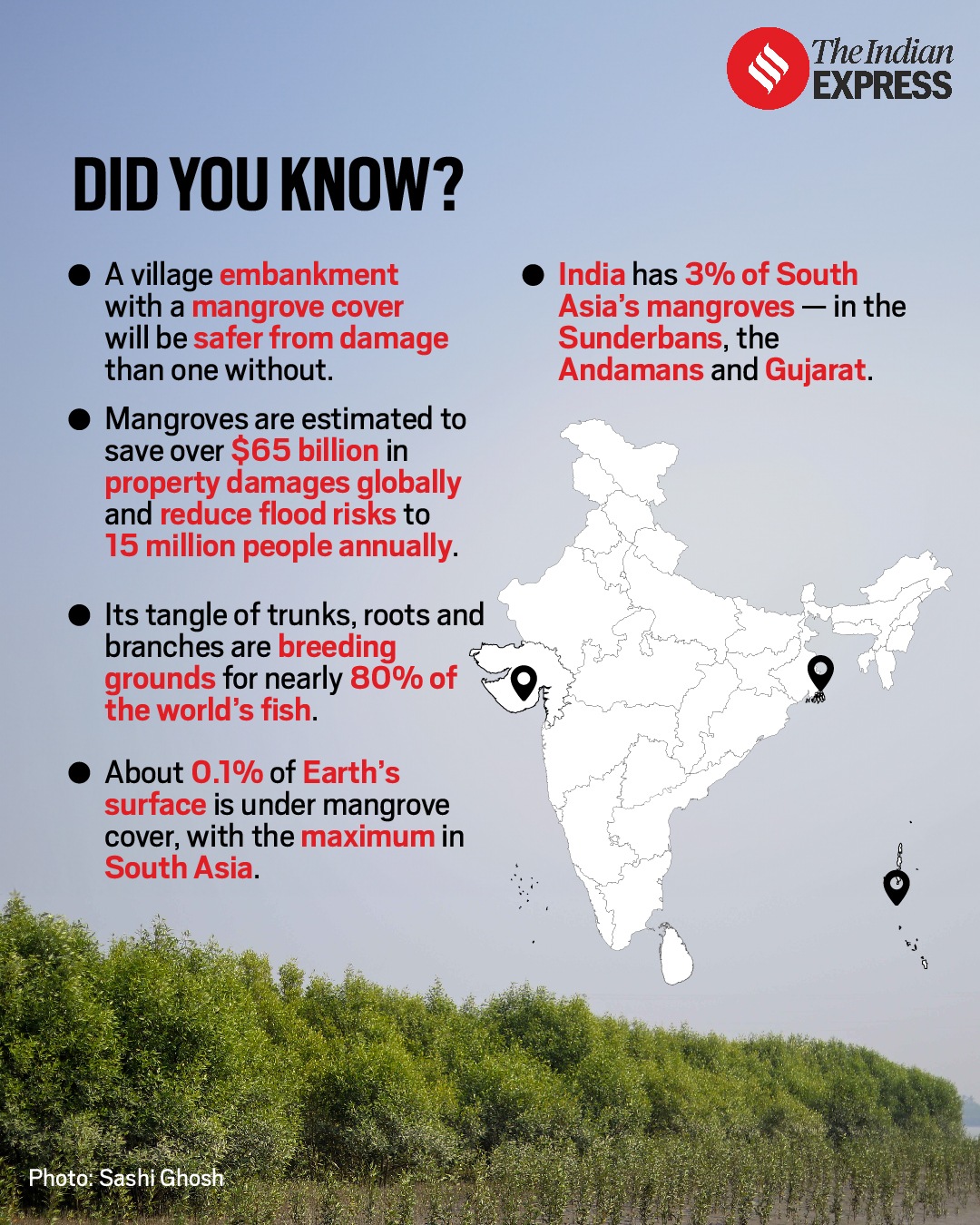

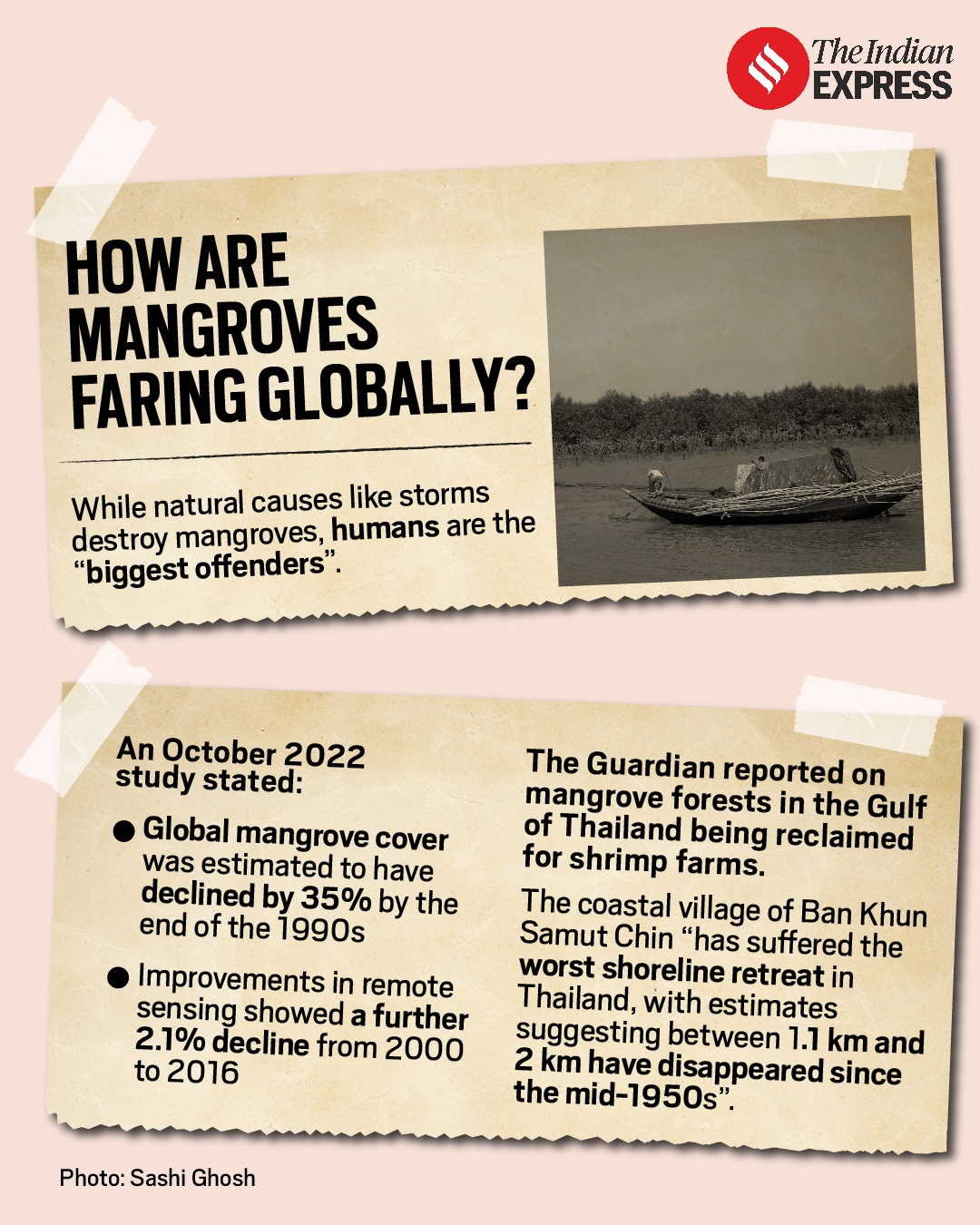

Historically, the Sunderbans, a complex network of islands set in the delta on the Bay of Bengal and spread across West Bengal and Bangladesh, has been battered by storm surge floods, cyclones, salinity intrusion, rising sea levels, land subsidence, water logging, coastal erosion and biodiversity loss.

It was after one such battering that the region took — the 2009 Cyclone Aila, which uprooted trees, flattened homes and rendered the shoreline bare — that Umashankar, who was born and raised in Chargheri before migrating to Murshidabad to teach geography at Jangipur High School, led people of his village in planting lakhs of mangrove saplings that now offer a dense forest cover for the village embankment. Chargheri is on Satjelia island, more than 110 km from Kolkata.

Lakhs of mangrove saplings now offer a dense forest cover for the Chargheri village embankment. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Lakhs of mangrove saplings now offer a dense forest cover for the Chargheri village embankment. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

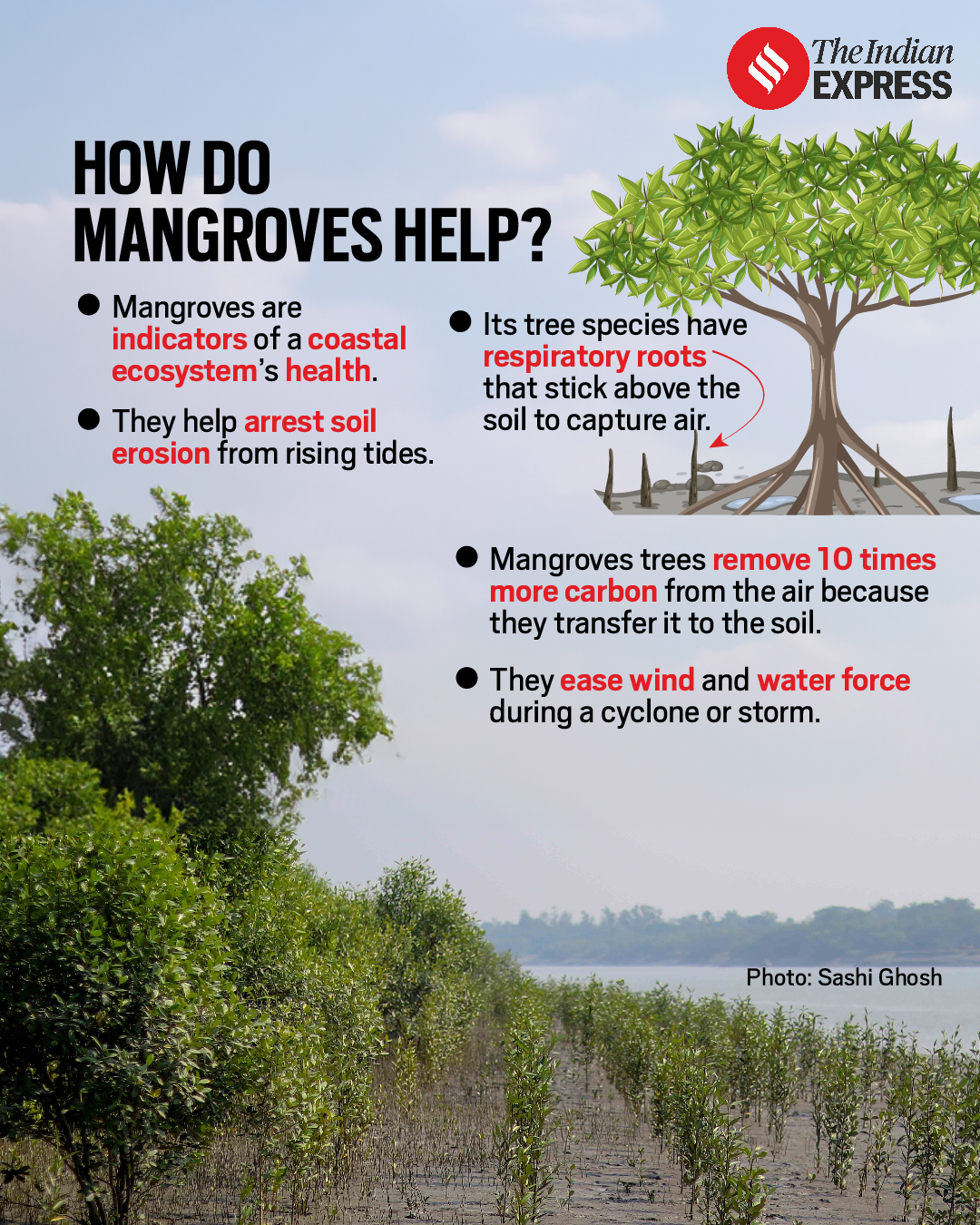

Standing on the low mud embankment of Chargheri, overlooking the mangrove forest that the community has created, it is possible to hear the river, which, even 15 years ago, would angrily tear through the embankment and flood their village every time there was a severe cyclone. Now, the river is hard to spot through the mangrove trees. Red, yellow and blue fiddler crabs scurry like jewels in the swamp at low tide. Snakes peep out of holes, birds flit overhead and locals say that during flowering season, it is impossible to stand for all the bees that cover the area.

Story continues below this ad

The mangrove trees that Umashankar and the others planted were meant to protect the village by taking the edge off future cyclones — which they did when cyclones Amphan in 2020 and Yaas in 2021 struck the Sunderbans. Chargheri had then escaped major damage. Since the forest came up, the embankments have never been breached. That alone would have been enough for the villagers, but unknown to them, their forest has also become also a rich carbon sink — i.e., a storehouse of carbon, a key contributor to climate change.

More than eight lakh mangrove trees now stretch beyond Chargheri to the other island villages of Satjelia, Gosaba and Kumirmara, each of them a powerful blue carbon sink – ‘blue carbon’ a term for carbon captured by and stored in the world’s ocean and coastal ecosystems.

Members of the Mangrove Army collect mangrove seeds, which come bobbing in the water from faraway forests, who gather them in mounds to sprout and then plant them. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Members of the Mangrove Army collect mangrove seeds, which come bobbing in the water from faraway forests, who gather them in mounds to sprout and then plant them. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Mangrove as carbon sink

Globally, carbon capture is being seen as one of the solutions to the climate crisis. In a paper published in 2022, Prof A K Paul from Vidyasagar University in Midnapore stated that the Blue Carbon Stock at four sites in Chargheri ranged from 214.72 to 280 mg per cubic centimetre.

“Blue carbon is a very important area of climate studies. To reduce the impact of climate change, we have to increase the Blue Carbon Stock by planting mangroves in mudflat areas. If the mangroves are removed from Chargheri and the forest area not protected, the carbon will be released in the atmosphere and the impact of climate change in the region will increase,” says Paul, an expert of coastal management who has been working in the Sunderbans since 1984 and been lending expertise to Umashankar’s activities since 2010.

Story continues below this ad

“The matter of carbon sequestering was unknown to me until a few years ago. That trees give us oxygen and absorb carbon dioxide is not the whole story. There are other things that trees do. That we have created a carbon sink without knowing it has increased our feelings of pride and wonder,” says Umashankar, who has authored the book, Baghe Dhora, Baghe Khaowa (‘Caught by Tigers, Eaten by Tigers’).

Evidence of anthropogenic climate change — that is, climate change resulting from human activities such as burning fossil fuels and deforestation — is around us. Corrective measures have centred around cutting carbon emissions, but it is not happening fast enough. Since 2009, when the term Blue Carbon was coined, researchers and other experts have become interested in the processes of carbon removal from the atmosphere as well.

With carbon dioxide (CO2) responsible for most of the global heating, carbon particles are not only being released in extremely large quantities, they have the ability to linger in the earth’s atmosphere for hundreds of years and warm it. Until the industrial revolution, the earth’s natural system had the capacity to maintain a stable level of atmospheric carbon. Today, the search is for ways to remove the trapped carbon from the air in order to keep the earth’s temperature from exceeding 1.5 degrees.

“Among all the natural systems, after seagrass, mangroves are the most efficient carbon trapping systems. The mangrove forest that Umashankar has created provides longevity to the village only as a co-benefit. The initiative’s advantage is the rapid carbon sequestration (capture) capacity of mangroves,” says Anurag Danda, Director-Sunderbans Programme of the WWF.

Story continues below this ad

Mangrove trees, which dominate the tidal belt, are particularly powerful in carbon capture. They absorb carbon from the atmosphere and deposit it in the soil, where the carbon can remain for thousands of years if undisturbed. Mangroves behave differently from other trees that also remove CO2 as part of the photosynthesis process — the latter store the carbon in their branches and roots but, when the tree dies, the carbon is released back into the air. Mangroves, on the other hand, transfer the carbon to the soil, where it stays unaffected even if the tree is destroyed. Researchers say that mangrove forests can remove 10 times more carbon from the air than other forests.

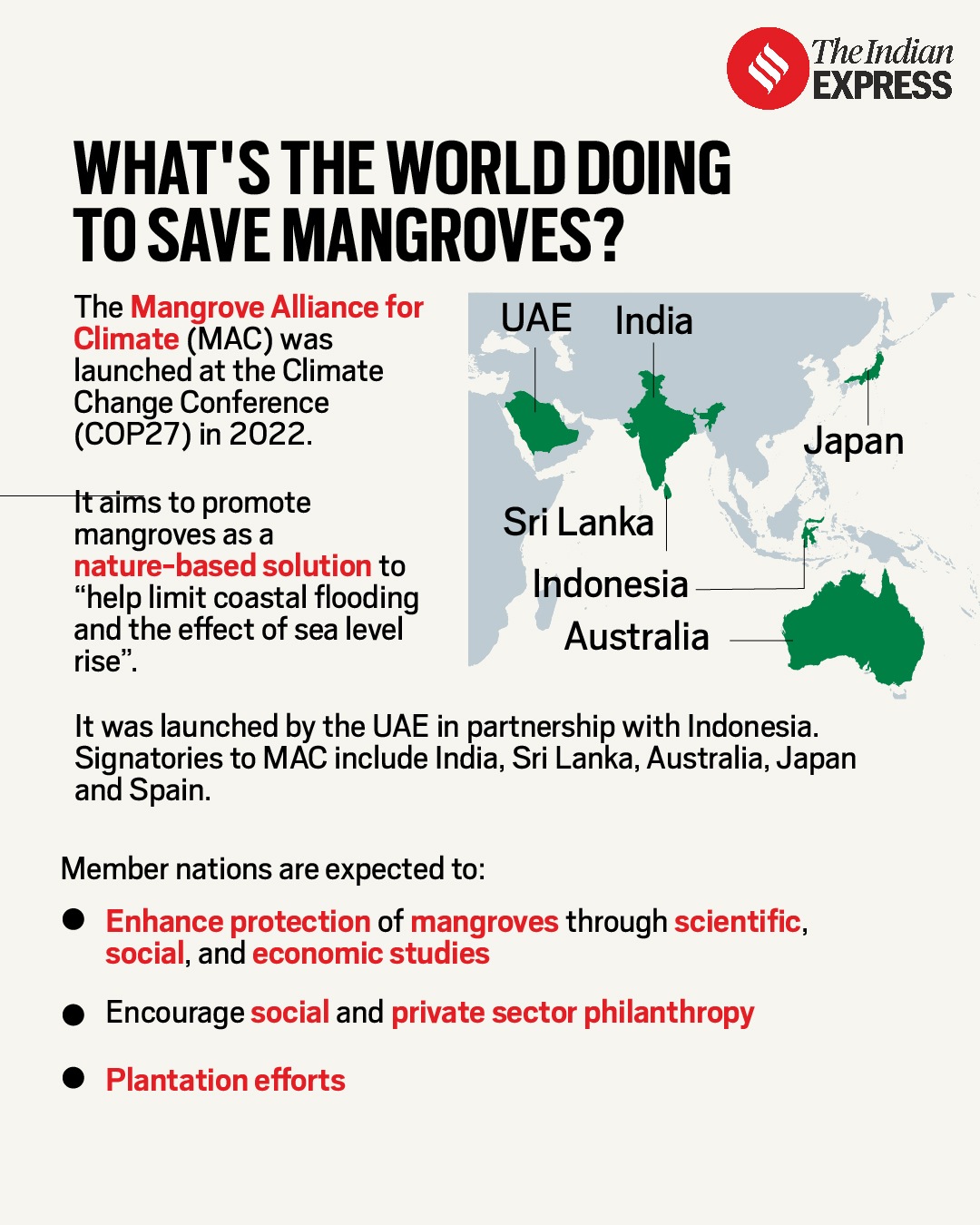

Mangroves have featured in climate conversations at high tables too. At CoP-27, held in Egypt last year, the Mangrove Alliance for Climate (MAC) was launched to unite countries, including India, “to scale up, accelerate conservation, restoration and growing plantation efforts of mangrove ecosystems for the benefit of communities globally, and recognise the importance of these ecosystems for climate change mitigation and adaption”.

In India, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented a new scheme in this year’s budget, called Mangrove Initiative for Shoreline Habitats and Tangible Incomes (MISHTI), to protect and revive mangrove ecosystems on the Indian coast.

Several NGOs and individuals are planting thousands of mangroves in the Sunderbans. After the devastation caused by Cyclone Amphan in 2020, chief minister Mamata Banerjee had announced that five crore mangroves would be planted in the Sunderbans under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act.

Story continues below this ad

But what makes Umashankar’s initiative unique is that it was born out of a very real and urgent need for survival.

The mothers as stakeholders

The deforestation of the Sunderbans goes back to Bengal’s colonial past. It includes the British government’s act of clearing thousands of acres of forest land to set up Port Canning in 1862 in the Sunderbans despite the warnings of Henry Piddington, the British meteorologist who coined the term cyclone. But as Piddington had predicted, a cyclone struck in 1867 with its eye passing over the Sunderbans.

Despite the doomed project, land continued to be reclaimed in the Sunderbans that saw steady streams of migrants. By the start of the 20th century, Scotsman Sir Daniel Mackinnon Hamilton had set up a cooperative on several thousand acres in the Gosaba islands. Today, the islands are home to 45 lakh people on the Indian side alone.

Marginalised financially and by caste and occupation, the locals borrow a term from the cricket World Cup to joke that they are “all-rounders” who are adept at fishing, crab hunting, farming and honey gathering, among others. Significantly, most of these activities involve resources from the forest. Thus, a mangrove forest in a village would run the risk of losing its cover.

Story continues below this ad

Since the women are always in or around the river — catching fish or drying cow dung cakes — they keep an eye on the mangrove forest. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Since the women are always in or around the river — catching fish or drying cow dung cakes — they keep an eye on the mangrove forest. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Dr Mehebub Sahana, Department of Geography, University of Manchester, UK, says that’s where Umashankar’s work stands out — by turning local communities into stakeholders in conserving the forest they built. “His dedication to restoring the mangrove forests has not only strengthened the region’s resilience to climate change and natural disasters but has also empowered local communities and raised awareness about the importance of environmental conservation,” says Sahana.

The school that Umashankar set up in Chargheri is part of that conservation plan — to send out the message that it is important not just to grow a forest but to ensure it lives on.

The Purbasha primary school came up this year on January 12 to mark the birth anniversary of Swami Vivekananda. Every day, at 7 am to 10 am, groups of children in yellow and green uniforms make their way to the classroom.

The 80 students are sons and daughters of the Mangrove Army, a group of mothers whose task is to protect the mangrove forest that the community has grown. “We did not have a school in our village. Our older children still go very far to study though roads are very bad. This school has been a blessing for us. The children get food, books, pencils, clothes and clothes on festivals like Durga Puja,” says Nandini Gharami, one of the 80 members of the Mangrove Army.

Story continues below this ad

Their work involves planting saplings and, most crucially, protecting the forest from villagers seeking to cut timber or the soft mangrove leaves to feed their goats. June to October is the best season to plant mangrove seeds — and Nandini and Sabita Mandal, whose children study at the school, “feel happy to come out to grow trees”.

Mangrove seeds come bobbing in the water from faraway forests and the women collect these, gather them in mounds to sprout and then plant them. During the peak season, they collect around 10,000 seeds in an hour. For the rest of the year, they participate in events such as Mangrove Bandhan, where the community ties rakhis to trees.

Worldwide, climate change experts have been advocating the need to include marginalised members of communities, including women. “Mothers have an emotion working in them. They want their children to do well and stay healthy. When mothers understand that we have created a school for their children’s well-being in mind, they become motivated to do their work well. If you involve a mother, then the entire family gets involved. Her children come with her and even her husband is supportive. I have found that, more than plantation, protection of trees is extremely tough,” says Umashankar.

Across the globe, climate change experts have been advocating the need to include marginalised members of communities, including women. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Across the globe, climate change experts have been advocating the need to include marginalised members of communities, including women. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

As they are always in or around the river, catching fish or drying cow dung cakes, the women keep an eye on the mangrove forest. Apart from the incentive of having a school for the children, the mothers are paid in the form of rations, saris, spectacles for their elders, among others. “If I had simply given them these items of necessity as gifts or relief, it would have become a one-sided affair. Instead, the Mangrove Army feels that they have earned these benefits for the work that they have done,” says Umashankar, who crowdfunds to sustain his initiative.

Story continues below this ad

On December 25, the forest will host a mangrove planting event with tiger widows as chief guests. Every family here has a story of a tiger attack, mostly of men who lost their lives as they entered the tiger-dominated forests by stealth to fish, catch crabs or gather honey. Their wives who are left behind confront a social and economic problem. Many are in their twenties and with few opportunities for employment or remarriage, the forest, with its promise of crabs, shrimps and a livelihood, draws many tiger widows back inside.

“We are trying to create a sustainable model by getting 50 tiger widows to participate in mangrove afforestation. Each of them will be paid 10 ducks and 10 hens. We want them to understand that they didn’t just come, take the ducks and hens and leave. They planted a sapling and, now, they will feel a responsibility in looking after the tree and the rest of the forest. This might seem like give-and-take but it is effective in our area,” says Umashankar.

Mangrove forests are also nurseries for shrimps and several kinds of fish. At least 11 families from Chargheri have begun spreading nets in the forest — which means that they, at least, will not endanger their lives to look for fish in the creeks of the forest.

Umashankar is also tying up with several institutes, whose students visit the forest on educational tours. It is a way to draw the younger generation from places beyond the Sunderbans and arouse curiosity and interest in persevering the islands.

“We want to ensure that children develop a fondness for the islands, its trees and water and sustainability. That way, their connection will be strong. If we want to develop trees, we have to develop people side by side,” says Umashankar.

The Purbasha primary school, set up by Umashankar as part of that conservation plan, has 80 students, the children of the Mangrove Army. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

The Purbasha primary school, set up by Umashankar as part of that conservation plan, has 80 students, the children of the Mangrove Army. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal) Lakhs of mangrove saplings now offer a dense forest cover for the Chargheri village embankment. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Lakhs of mangrove saplings now offer a dense forest cover for the Chargheri village embankment. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal) Members of the Mangrove Army collect mangrove seeds, which come bobbing in the water from faraway forests, who gather them in mounds to sprout and then plant them. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Members of the Mangrove Army collect mangrove seeds, which come bobbing in the water from faraway forests, who gather them in mounds to sprout and then plant them. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Since the women are always in or around the river — catching fish or drying cow dung cakes — they keep an eye on the mangrove forest. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Since the women are always in or around the river — catching fish or drying cow dung cakes — they keep an eye on the mangrove forest. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal) Across the globe, climate change experts have been advocating the need to include marginalised members of communities, including women. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)

Across the globe, climate change experts have been advocating the need to include marginalised members of communities, including women. (Express photo by Umashankar Mandal)