Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

The Ultimate Warriors

The sport was clean by 1996, but poorer due to both fan and talent attrition.

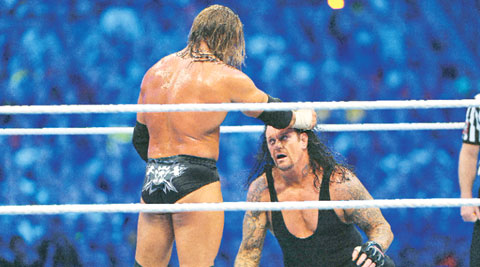

Last week, at Wrestlemania XXX, the organisers showed the greatest sign of being on the verge of yet another epochal leap by paying tribute to its various generations. (Getty Images)

Last week, at Wrestlemania XXX, the organisers showed the greatest sign of being on the verge of yet another epochal leap by paying tribute to its various generations. (Getty Images)

Were you,like The Undertaker,a force of retribution from the dark side? Or Yokozuna,who could devastate with a Banzai drop? As WWE Wrestlemania turns 30, Aditya Iyer tells you what the heroes of pro-wrestling, even if they were flamboyant gladiators of a circus act, meant to a kid growing up in the Nineties.

Nellai Apartments, one of the many predominantly south Indian housing societies that generously mushroomed in central Bombay in the late 1980s, used to wake up on Sundays to classical music. The hypnotic voice of MS Subbulakshmi would stream out of several balconies, mixing out of tune with the heavy notes of ML Vasanthakumari wafting graciously out of other netted windows.

The unsteady collaboration of the two Carnatic heavyweights would make the Maharashtrian on the third floor, a Hindustani aficionado, shudder. On cue, he would turn up the dials on his CR Vyas-playing recorder to maximum, pointing the perforated speakerbox earthward, hoping that it would somehow keep the negligible north-south balance in the building alive.

It was a heady concoction, of course. Heady enough to quake us single-digit-year-olds out of bed, forcing us to instinctively reach for our cricket bats and head downstairs to the common compound area. This cacophony was our ever-reliable alarm clock for as long as anyone cares to remember; year after year, month after month, week after week and weekend after weekend.

Only, on one Sabbath 21 years ago, Nellai didn’t wake up to classical music. It woke up to two far more potent occurrences — the onset of the monsoons and what seemed to be a society-wide robbery.

Mattresses were missing from most households. As were sofa cushions, pillows, pillow covers, towels, bedsheets, bedspreads and trendy tablecloths. One flat even missed its elder statesman, the grandfather. All houses, without exception, were barren of children.

On this thunderous and electrifying dawn and under the raftered confines of the society’s Ganesha temple, the grandfather stood with his veshti rolled up to his knees and his arms spread like a condor. WWF Thaatha, as we fondly called this 80-year-old who always took our side against the disciplining parents, was taking his enactment of the referee-cum-trainer-cum-Vince McMahon (the godfather of this sport) very, very seriously.

All around him, 30 or so of us children, draped in bedsheet-capes and pillowcase-masks (eye holes neatly carved out with a pair of stolen scissors), threw one another over the mattresses and cushions placed precariously over the cold, damp and stone temple floor.

“Kuthu! Adi! Kizhe podu!” WWF Thaatha would exclaim through his denture-void jaws, demanding us to “punch, hit and throw down”. We would then chuckle at his ignorance and take turns to patiently explain to him that this was no cheap mud pit with pehelwans. No. We were WWF Superstars and this was a reenactment of Royal Rumble VI, the second greatest annual pay-per-view under the WWF banner. The moves, hence, had to be choreographed with utmost care.

“No, Thaatha. We know what we’re doing,” one of us would bellow. “Now it’s time for Papa Shango to throw Ric Flair to the ropes (the temple’s clambering metal gate) and clothesline him. Then, Mr Perfect will elbow drop Jerry “The King” Lawler and eliminate him with a suplex over the ring.”

Lawler was played by the boy who remembered to bring his mother’s headband (to wear as a crown) along. And the role of Mr Perfect was unfailingly passed on to the kid who didn’t forget to whisk a towel (used during his dramatic entry) away from his snoring household. These were the variable characters. There were, however, a few constants.

The tallest boy was always The Undertaker, the shortest Bob Backlund and the fattest (played by yours truly, until a fatter and older building bully moved in a few years later) Yokozuna. It was as good a time as any to be overweight and shirtless, for according to the script of Royal Rumble VI (memorised wholly, thanks to our friendly neighbourhood VHS rental store), Yokozuna was supposed to win the main event and get his title shot against Bret “The Hitman” Hart at the flagship event — Wrestlemania IX. Once that cassette was in circulation, it would unfold in this very temple.

With only Macho Man Randy Savage left in the ring (just like in the script), all that was left was to execute my finishing move, Yokozuna’s finishing move, the ferocious Banzai.

Having dragged him to the turnbuckles (played by a wooden chair), I climb atop to jump back first on his face. Eyes twinkling with dreams of glory, I land perfectly on my backside. Only, Randy Savage (and this is not according to the holy script) has moved out of the way and is standing upright in fear. The angry society elders, our parents, have finally arrived — almost all at once.

Taking sinister advantage of the situation at hand, the boy playing Ultimate Warrior, long disqualified and whose generous coating of face paint was by then peeling off, re-entered the ring and managed to pin me down, all the while screaming: “Thaatha, Thaatha, say one-two-three!” Clapping one palm over the other in succession like a serious listener keeping taalam to DK Pattammal, WWF Thaatha, who clearly had no time for authority either, went: “Onu, rendu, moonu.” Simultaneously, the temple bell rang thrice. The match was over. Ultimate Warrior had become, at least in our world, Royal Rumble champion.

Somewhere, Chuck Palahniuk, the creator of Fight Club, must have smiled. Somewhere else, Vince McMahon, the father of modern day pro-wrestling, was surely laughing his way to the bank.

Vincent Kennedy McMahon is the Socrates of pro-wrestling. Or as a character in the teen flick Road Trip suggests: “Socrates is the Vince McMahon of philosophy.” In the early ’70s, McMahon, a wannabe wrestler himself, joined his father’s small-time wrestling business, based out of Massachusetts, as a ring announcer. By the early ’80s and after his father’s death, McMahon took over the reins and renamed his roadshow WWF. Or World Wrestling Federation. It was a preposterously ambitious name for an insignificant circus act.

But McMahon had plans; although one highly doubts if even he believed that his company would at some point be publicly listed as a billion-dollar franchise.

Just a week ago, his brand completed the 30th edition of its flagship pay-per-view event — Wrestlemania XXX. A far cry from the days of waiting for our trusted video rental man to make a pirated copy, Wrestlemania XXX was shown on Indian television (bought exclusively from WWE Networks) just hours after it ended in New Jersey.

Here, on this stage, the original Ultimate Warrior (real name James Hellwig) was inducted into the sport’s Hall of Fame. As he stood there, older, devoid of face paint and crying, I thought of calling his Nellai version up (who I heard had become an investment banker), having lost contact some 20 years ago. I eventually did a couple of days later as the Warrior was in the news once more; on this occasion, perhaps for the last time. Outside his hotel room parking lot in Scottsdale, Arizona, Hall of Famer Hellwig collapsed and died. He was 54.

I make the call, hoping an old friend remembers me. He doesn’t, until I remind him that I played Yokozuna in the temple fight. “Of course!” the ole’ warrior barks back. “I apologise for that. That was a cheap move on my part, quite like many of the moves back in the old days of WWF. Or is it WWE now?”

World Wrestling Federation had long been rechristened World Wrestling Entertainment, thanks to a lawsuit filed by the World Wildlife Fund, who weren’t so keen to share their acronym with a bunch of men in spandex. So in the summer of 2000, McMahon’s creative team ran a campaign called “Get the F Out” and turned a problematic situation into something fun. But this is something the brains behind this pro-wrestling franchise excel at.

When allegations of rampant drug and steroid use hit the business in 1994, McMahon exclaimed that the era of the Golden Generation — the likes of Hulk Hogan and Andre the Giant, men who helped shape the sport — had ended. But never one to give up, wrestling’s only billionaire gushed that the New Generation Era had begun, where younger and drug-free wrestlers (wrestlers that kids could ape and relate to in south Indian temples) would take the sport ahead.

The sport was clean by 1996, but poorer due to both fan and talent attrition. Several franchises based on the WWF model cropped up but were serving a wider fan base. The likes of WCW (World Championship Wrestling) catered to a teen-cum-adult audience by featuring in its shows explicit violence and a hardcore form of wrestling. Many big names, such as Hitman and Goldberg, moved over.

So, in order to keep abreast, the old machine got rid of the masks and face paint and brought in extreme props such as tables, ladders, chairs and sledgehammers, while also signing on mean-looking and chiselled anti-heroes such as Stone Cold Steve Austin and The Rock.

With far more offensive language and litres of blood split in the ring, the fans came crawling back during what is now known as the Attitude Era. Then, they simply refused to leave, staying true to McMahon’s fiefdom, all the way through the Ruthless Aggression Era — where the new age of brutes was ushered in by the likes of John Cena, Brock Lesnar and Randy Orton.

Last week, at Wrestlemania XXX, the organisers showed the greatest sign of being on the verge of yet another epochal leap by doing what they had seldom done in the past — remembering its heroes and paying tribute to its various generations.

The great Hulk Hogan (Golden Generation), Stone Cold Steve Austin and The Rock (both from Attitude) turned the Superdome in New Orleans into a mutual admiration club as they chugged down cans of beer in the “squared circle” (as the ring is known in WWF) and discussed just who among them had a greater influence on the sport. Arguably, however, none had a deeper impact on pro-wrestling fans than the man who still continues to fight under, perhaps, the most famous ringname of all time, The Undertaker.

The Deadman, as he is known informally, boasts of longevity shown by none in the real sporting world, apart from say Sachin Tendulkar (incidentally, Tendulkar’s great rival from the ’90s, Shane Warne, is said to be a big fan). And quite like Tendulkar, ’Taker has a legacy to be proud of. Since 1992 (well before we first laid hands on the wrestling VHS), The Undertaker had never lost a match in Wrestlemania. The WWF (and trust them to come up with something as ridiculous) called it “The Greatest Streak in Sporting History”.

Then, the Streak ended last Sunday at 21, with Brock Lesnar “achieving” what no one else had in the sport’s history. It didn’t go down too well with my investment banker friend. “I thought the Streak would outlast us, our lives,” he says, only half joking. “Anyway, I wonder if the kids today still dress up as ’Taker in their mock fights. And I wonder if they get a telling off from their parents the way we used to.”

The parents weren’t happy. Far from it. We were beaten, punished and grounded. But there was precious little that they could do to prevent an outright invasion of our young minds. Quite like when The Beatles landed in the USA in 1964, the colourful and flamboyant entertainers from the universe of pro-wrestling arrived at our doorstep in the early ’90s and turned it upside down. Only, instead of screaming girls going weak in the knees, here were screaming boys going weak in the solar plexus.

So what if the temple was monitored with a watchman and a sign that read: ‘Kovil: For strictly religious purposes only’? We staged (and staged is the right word) our new religion on building terraces. When the terraces were locked and put out of bounds, we performed our leg drops, low blows and wheelbarrows in schoolyards. And when we were suspended for doing so, we spent our days at home, playing those revolutionary trump cards or simply imitating our Greek gods in front of mirrors.

We must have terrorised the elders, running with scissors like Brutus “The Beefcake” Barber, lugging dustbin barrels on our shoulder like Duke “The Dumpster” Droese and sticking uncut radishes (carrots would do too) on our cricket helmets to look like the viking lord, The Berzerker.

We must have scandalised the visiting uncles and aunts who made the sincere mistake of requesting us to recite a Carnatic vocal or two. For when we didn’t respond and they pressed us further with questions such as ‘Who is your favourite — MS Subbulakshmi or ML Vasanthakumari?’ we would grunt back and take a strong whiff of our armpits, because that’s what the Bushwhackers would’ve done.

They were perhaps nothing more than trailer trash, as Mickey Rourke’s portrayal of an ageing veteran in The Wrestler (2008) strongly suggests. But we did our bit in making them feel, at least momentarily, like heroes. Perhaps even legends.

Ultimate Warrior, in his Hall of Fame acceptance speech, summed it up best. “No WWE talent becomes a legend on his own,” he said. “Every man’s heart one day beats its final beat. His lungs breathe their final breath. And if what that man did in his life makes the blood pulse through the body of others, something larger than life, his spirit, will be immortalised.”