Subhash Chandra Garg at Idea Exchange: ‘On electoral bonds, SC must not overreact. If it calls them illegal, we go back to cash’

As Finance Secretary, Subhash Chandra Garg has worked with three finance ministers — Arun Jaitley, Piyush Goyal and Nirmala Sitharaman. Between mid-2017 and mid-2019, he presided over the implementation of big moves like demonetisation, electoral bonds and GST.

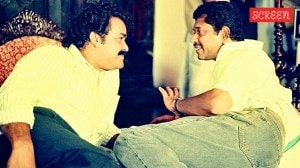

Former Finance Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg (right) in conversation with P Vaidyanathan Iyer at The Indian Express office in Noida. (Express photo by Gajendra Yadav)

Former Finance Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg (right) in conversation with P Vaidyanathan Iyer at The Indian Express office in Noida. (Express photo by Gajendra Yadav)Former Finance Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg on transparency in electoral bonds, the Government’s slow-pedalling of big ticket reforms, disinvestment and institutional autonomy. The session was moderated by Executive Editor P Vaidyanathan Iyer

P Vaidyanathan Iyer: Let me begin with electoral bonds. Although the Supreme Court has posed certain questions, what’s your take on transparency in raising political funds? Questions are being asked about the ruling party or its government being privy to information not available to others.

Whenever an economic policy is being made, we should ask ourselves what is the problem we are trying to solve. And what is the best solution. Then we may find good, practical solutions. In 2017, there were two ways of political funding. One was transparent, through company donations that were also eligible for income tax deductions. The second was through cash because there was a rule that if you contribute up to Rs 20,000, you don’t need a receipt. So 95 per cent or more donations were coming in cash.

Who is the principal donor? Salaried people don’t make donations. Cash contribution actually emanated from companies, traders and businessmen. So, it degenerated into a system where companies, either by overbilling or underbilling, or by siphoning off cash from company accounts, would convert that into legitimate money and donate to the concerned political party. As I understood, the then Finance Minister Arun Jaitley’s measure, which was brought in the 2017 Budget, showed the way by which you could eliminate the cash transformation of legitimate money.

For whatever reason, Indian businessmen were not prepared to tell the world who they were funding and resorted to suspicious methods. Hence an attempt was made to find a solution from cash to an account-based donation. That was the genesis of the electoral bonds.

When the scheme was designed, it was a kind of mixed solution, not a perfect one. We thought that if on both ends of the electoral bonds, we bring it on to the books and make it white — not black, not cash — then probably we would make progress. So we made sure that the company which wants to donate would buy it out of its legitimate income through the bank account, which is KYC-compliant, and would buy the bond through that system. That was one end of the improvement. Now you don’t have to convert cash, you just buy bonds through your account. And that record is available if ever required.

After 1991, it was the Vajpayee government that made a big change. But today, there are huge supporters within the larger ecosystem, who think that the public sector is sacrosanct and must be protected

Likewise, political parties also had a problem, because when the cash was received, much of it was not even accounted for. With electoral bonds, they could account for everything because they could receive this only in a KYC-compliant bank account. Then they could make expenditure through a legit account by giving cheques, using Paytm or whatever mode.

We had a third objective, to make sure that fake bonds don’t come into the system. So we created three layers of security. One end was that you bought from this account, so that account was verified. Second, it carried an invisible ID number. And the third one was the political party. We were aware that if the impression got around that the government of the day or the agencies of the day could actually get information on who was donating to whom, the scheme would not take off. That confidence needed to be built in, to the extent possible. And that is why these three Chinese walls were created within the SBI (State Bank of India). Legally, the issuer would not know who had deposited. So there would be no reconciliation in the SBI that a particular bond was bought by a certain entity and deposited into a certain political party’s account. It has been debarred from maintaining this record. Only in criminal cases is the SBI required to produce some record of the transaction in a court of law and within the purview of the investigation.

There is a lot of confidence in the business community because of the bonds. That is why about Rs 14,000 crore worth of donations have been made. And 35 to 40 per cent has been received by Opposition parties. It’s not that 90 per cent has gone to the ruling party.

P Vaidyanathan Iyer: There is only one issuer, SBI.

Yes, but they are not supposed to maintain the bond-by-bond account of who bought what. They will maintain a record of who all have bought but not which bond has been bought by whom. It is as difficult as getting information about your private bank account or your tax return and health records. But if your other private information can be accessed, this can as well be accessed too.

Former Finance Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg

Former Finance Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg

P Vaidyanathan Iyer: Hence the information problem will remain?

That will remain but then you have to violate both the law and the bank’s norms. I think the Supreme Court must not overreact. Suppose it says this is illegal. Then you go back to the cash situation.

Harish Damodaran: Isn’t this creating a new system, where big parties are able to get funds seamlessly from big corporates but smaller parties and traders are out of its ambit?

The cash route is still available for smaller parties. There is a condition that says a party must get at least one per cent of the vote in an election to be eligible for an electoral bond. That’s why the old route isn’t closed.

In the Modi govt’s first term, in my judgment, institutions were more independent, managed by more capable people. In the second term, it has been more about loyalty and commitment. So there’s an enormous change

Ravi Dutta Mishra: Isn’t it easier for the government to get information from the SBI? Would it have been difficult if the RBI (Reserve Bank of India) had issued it? Even former RBI Governor Urjit Patel mentioned there was a disagreement.

The Government has easy access to any kind of information. So, there is nothing very special about the information access as far as electoral bonds are concerned. Electronically, there are many ways to access information which you may not even be knowing about.

As far as the RBI is concerned, the original scheme envisaged not only RBI but many banks as issuing bonds. At that stage, the RBI had actually objected, saying this bond should not become a currency in circulation. It had asserted that it was a monetary authority, not a political one. How could you take care of that? By ensuring the bond doesn’t remain in operation for long. We initially thought of seven days but because of practical difficulties, extended the period to 15 days. The RBI had agreed to this arrangement and this information had come into the public domain. But my Joint Secretary at that time, following the practice of checking with the concerned agency before a scheme is formulated, sent it to the RBI. That’s when Urjit Patel took a unilateral stand, saying the bond should be digital and issued by the RBI so that there was no possibility whatsoever of this becoming a currency in operation. But if you make it a digital bond with all ends, it suffers the same inadequacies of being completely transparent; it wouldn’t have worked. That’s why we went with the SBI. Besides, had the RBI done it through a single account, both donors and political parties would have to open an account in the RBI.

Former Finance Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg (right) in conversation with P Vaidyanathan Iyer at The Indian Express office in Noida. (Express photo by Gajendra Yadav)

Former Finance Secretary Subhash Chandra Garg (right) in conversation with P Vaidyanathan Iyer at The Indian Express office in Noida. (Express photo by Gajendra Yadav)

P Vaidyanathan Iyer: As you said, around 60 to 65 per cent of the donations has gone to the ruling party. Since that raises questions, do you think there are improvements possible in the bonds issued?

If you are a little practical, why do businessmen or companies donate funds? They are hoping for some favour or seeking to protect their businesses. In the states ruled by Opposition parties, the latter have got the major share of electoral bonds.

There’s confidence in the business community about electoral bonds. About Rs 14,000 crore donations have been made. And 35 to 40 per cent has been received by Opposition parties. It’s not that 90 per cent has gone to the ruling party

Story continues below this ad

P Vaidyanathan Iyer: This government has put fiscal policy on the backburner and is not as serious about fiscal deficit. Except Air India, nothing has happened on privatisation. Your take?

In the first term, the government was completely fixated on getting to three per cent of the GDP as fiscal deficit. It announced the roadmap in 2014 itself and brought amendments in the FRBM Act. The debt target was also to be 40 per cent by 2024-25. In the first term, privatisation and strategic disinvestment were the big policy changes captured in that ‘Maximum Governance, Minimum Government’ mantra. This intent continued until February 2021 as was evident in the Budget. But for that delayed privatisation of Air India, which was just to get something off your back, disinvestment has plummeted to Rs 13,000 crore in one year, whereas that figure was Rs 1 lakh crore at least two or three years in the previous term of this government.

The big change was the number of public welfare schemes, be it the housing, toilet and gas schemes. So, household was viewed as a priority. In the second term, even the Jal Jeevan Mission hasn’t met targets. In the first term, in my judgment, institutions were more independent, managed by more capable people. In the second term, it has been more about loyalty and commitment. So there’s an enormous change. There is hardly any economic policy or reform and what is touted as reform today, is not reform at all. So obviously, something else has got primacy.

P Vaidyanathan Iyer: How do you see the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) influencing the Finance Ministry between the two terms?

It depends upon the personality and preferences of both the Prime Minister and the Finance Minister and how that equation or the relationship evolves. Mr Narendra Modi is a very hard taskmaster, a hard-working person himself. The kind of issues he gets himself involved in is amazing. But that also leads to an enormous amount of centralisation by not giving as much space to the other ministerial colleagues. In the first term, there was a very pronounced preference to operate through the secretaries. However, Modi is not the first Prime Minister to do so. Even Indira Gandhi was a great centraliser. The PMO actually came into its own during her tenure, not before.

Arun Jaitley felt that running the government should be left to the secretaries whereas Nirmalaji is more into detailing rather than confining herself to broader aspects. But it’s a fact that the Prime Minister is the chief executive. And if he also happens to be the principal political persona of that particular party, then a lot of decision-making will shift to that side.

Aanchal Magazine: On the question of giving RBI surplus to the government, you gave a strong dissent note to the Bimal Jalan Committee on RBI’s Economic Capital Framework. There were appointments in the RBI board as S Gurumurthy was included. Did that impact the autonomy of the institution?

Whatever happened during that time, which I have also recounted, testifies to the fact that the RBI was independent. The government was trying to get a foot in the door. If the government was all powerful, it would not have done any of those things it did. Mr Gurumurthy’s appointment was handled by the deputy Finance Secretary, not by me.

The RBI’s autonomy is the most needed in the monetary policy space. In other spaces, it works as the agent of the government. For example, even in currency and debt management, it’s an agent of the government. If you go beyond what is rationally and systemically permissible, then we’ll put a brake. Putting a brake on the government requires autonomy. Now, the perception that RBI is running away with too much independence was because Urjit Patel had stopped having pre-monetary policy consultation with the Finance Minister, which had been a tradition for ages. That is why the government had to think of finding some solution.

That explains the change of the board or bringing in Section 7 of the RBI Act. The battle we fought in the RBI board was to actually reassert that, at least in the board, a member has as much independence or as much authority as the other board members. Had there been a reciprocal, even basic consultative approach, changes wouldn’t have been required.

Sukalp Sharma: You were one of the first people in this government to have proposed disinvestment of a big oil company. However, the BPCL (Bharat Petroleum) disinvestment failed spectacularly. Was that a problem of intent or process?

Normally civil servants and even ministers are so much steeped in the culture of the public sector that they are pathologically against privatisation. Now, the push for privatisation can come either from big distress, like it was in 1991, or when you have a very strong Prime Minister. When Modi took over, he had the sense and intent to privatise because he had seen private businesses growing very well in Gujarat. My sense is that now even he has lost the appetite or interest in privatisation. So today, both the core government, which had never been interested, and the driver are not interested.

Sukalp Sharma: How was Mr Vajpayee able to do it better?

I think he was completely committed to the process. He was also aided by a very strong-willed Disinvestment Minister, Arun Shourie. So after 1991, it was the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government that made a big change. But today, there are huge supporters within the larger ecosystem, who think that the public sector is sacrosanct and must be protected. Touching it is becoming more and more difficult.

Shahid Pervez: Do you think Arun Jaitley was in the loop on demonetisation? What about your own shifting position on demonetisation from initially defending it to later going on to say it’s a complete misadventure?

The demonetisation was announced the day I (then an Executive Director at the World Bank) met Mr Jaitley because it was a part of convention that you had to brief the Finance Minister (before returning to the US). It was around 6 pm that I met him and we talked about many things. He seemed quite relaxed and told me that he would also leave soon as he had a wedding to attend. I don’t think he was such an actor that he could hide. Though he defended the move on TV, purely based on my observation, I think he didn’t know.

In my judgement, there is no decision of the government which is completely black or white. There were certain positive effects of demonetisation. The ratio of currency in circulation to GDP had not reached pre-demonetisation figures, there was clear evidence that stone-throwing and other activities in Jammu and Kashmir had come down and fake notes had reduced substantially. And though this was not the stated purpose, it had given some fillip to digital payments as well. So I defended it but there were two weak links. One of the weak links was the logic behind introduction of a Rs 2,000 note when you wanted to abolish the Rs1,000 and Rs 500 ones on the ground of them being of a larger denomination. That’s why I clarified that Rs 2,000 notes were not intended as a kind of permanent arrangement.

The second argument that I found difficult to defend was when somebody mentioned that the Government expected Rs 5 lakh crore worth of notes not coming back into the system. I said I had studied the files but there was no such mention. Then somebody told me the Attorney General had said so in the court. But this has become history by now. I don’t think there’s much change in the way, except nuances, when you are in the government defending it or when you are outside, and you can speak the whole truth. There has been no essential change in my opinion.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05