Anonna Dutt is a Principal Correspondent who writes primarily on health at the Indian Express. She reports on myriad topics ranging from the growing burden of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and hypertension to the problems with pervasive infectious conditions. She reported on the government’s management of the Covid-19 pandemic and closely followed the vaccination programme. Her stories have resulted in the city government investing in high-end tests for the poor and acknowledging errors in their official reports. Dutt also takes a keen interest in the country’s space programme and has written on key missions like Chandrayaan 2 and 3, Aditya L1, and Gaganyaan. She was among the first batch of eleven media fellows with RBM Partnership to End Malaria. She was also selected to participate in the short-term programme on early childhood reporting at Columbia University’s Dart Centre. Dutt has a Bachelor’s Degree from the Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Pune and a PG Diploma from the Asian College of Journalism, Chennai. She started her reporting career with the Hindustan Times. When not at work, she tries to appease the Duolingo owl with her French skills and sometimes takes to the dance floor. ... Read More

Cancer medical bills: Does the new govt exemption bring relief to patients?

A patient family explains how they balance costs between life-saving drugs and hospital care

A new cancer drug, promising fewer side effects and better outcomes, is now a ray of hope. (Express Illustration)

A new cancer drug, promising fewer side effects and better outcomes, is now a ray of hope. (Express Illustration)After her lung cancer diagnosis, 70-year-old Meenakshi Sinha* from Delhi found herself writhing in bed most of the time with aches, pains, diarrhoea, nausea and itches from her chemotherapy sessions. A new cancer drug, promising fewer side effects and better outcomes, is now a ray of hope. However, this hope comes at a high price.

Her doctor prescribed her the targeted therapy drug Osimertinib — one of the three drugs which the government recently exempted from import duty. It blocks the protein that helps the cancerous cells multiply and works well in lung cancers, which are difficult to treat and shorten lifespans. This targeted therapy is better than existing cancer protocols and can be prescribed after the tumour is removed surgically, or even as a first-line treatment when the cancer has metastasised.

But it costs around Rs 1.5 lakh per strip of ten pills, or Rs 4.5 lakh a month for 30 tablets. Since its manufacturer, AstraZeneca, now sells 30 tablets for Rs 1.5 lakh as part of a patient support programme, the 10 per cent drop in prices means the cost comes down to Rs 1.35 lakh per month. Still steep for many patients and their families. “This is a maintenance drug, meaning one has to continue taking it till one becomes resistant to it. At the time of prescribing the drug, the doctor asked us to go for it only if we had the means to continue it for, say, five years,” says Meenakshi’s daughter-in-law, Yamini*.

The cost dilemma

Dr PK Julka, director of Max Oncology Daycare Centre, admits that newer cancer therapies have created a dilemma for patients and their families, who know that these would lead to better outcomes but cannot afford it. Some of them, therefore, choose to be part of clinical trials. “One of my stage IV lung cancer patients was enrolled in a trial for one of these therapies, which she could not afford. Not only has she survived, she has led a life with minimal disease for six years now. This is unheard of in advanced stage lung cancer patients. But for many, this therapy is not an option because of the high cost,” says Dr Julka.

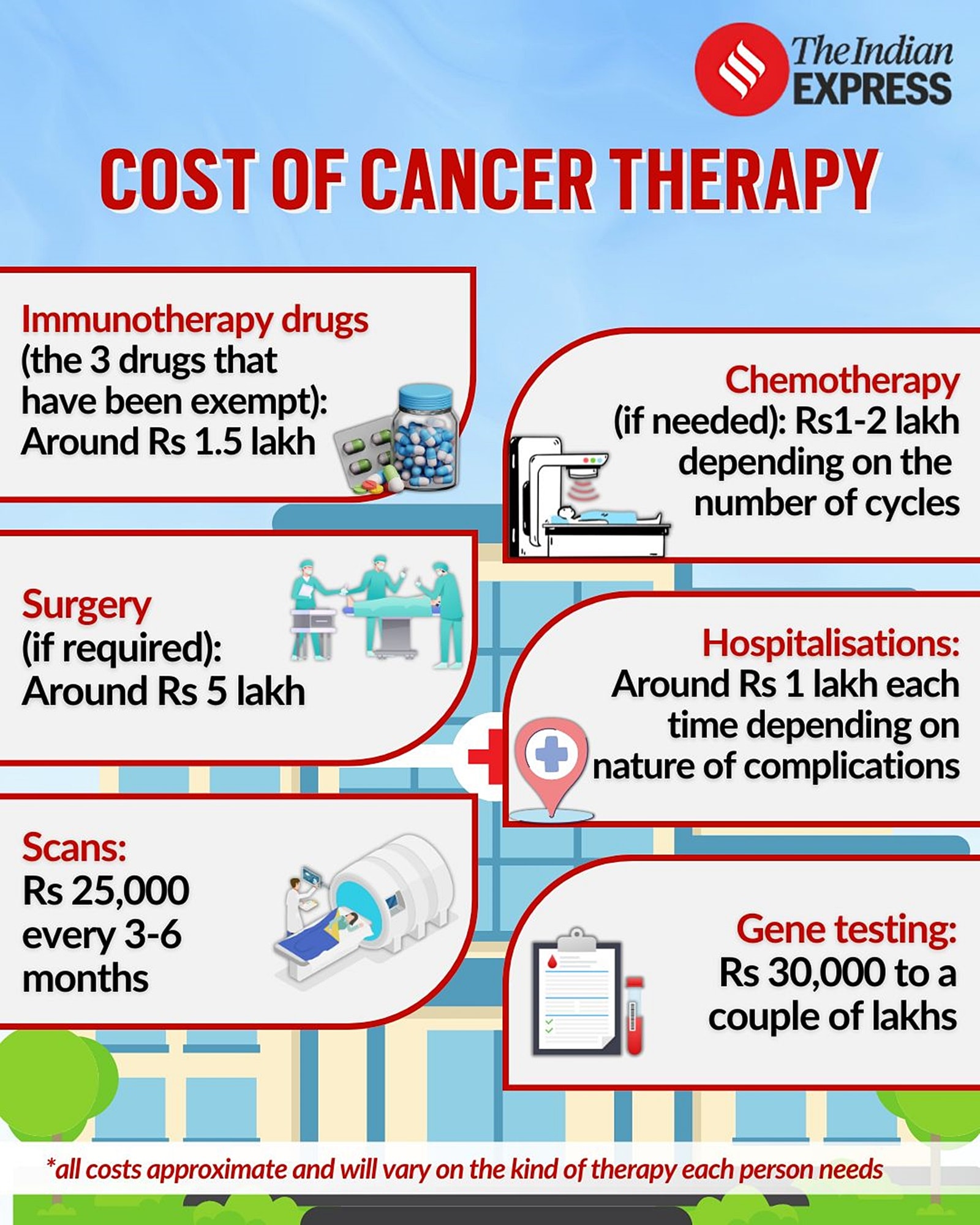

Understanding the cost of cancer therapy. (Gfx by Khushpreet Kaur)

Understanding the cost of cancer therapy. (Gfx by Khushpreet Kaur)

Do generics help?

The steep price barrier is driving many patients to explore options with generics. In fact, Yamini decided to go for them only after meeting the family of another patient, who had used generic versions of the AstraZeneca medicine and seemed to be doing well. “The generic drug costs around Rs 10,000 to 20,000 for 30 tablets, much lesser than the original drug. Our oncologist did not tell us about these generics, our GP did. My mother-in-law’s side effects have reduced. Reducing the cost of a Rs 1.5 lakh medicine by just Rs 15,000 doesn’t really change the financial implications for the family much. Generics are a big deal,” says Yamini.

It is this need that has made Beacon Pharmaceuticals, a Bangladeshi pharmaceutical company that develops generic versions of the medication, much sought after. While Osimertinib — sold as Tagrisso — is still under patent held by AstraZeneca, Beacon argues that it can legally make the generic version, called Tagrix, as a manufacturer in a least developed country (LDC) as per patent laws of the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Drug plus other costs

Drug costs are not the only hurdle, there are allied costs of maintenance and follow-up therapies as well. Says Dr Abhishek Shankar, oncologist at the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Delhi, “The staples of cancer care, such as surgery and radiotherapy, cost a lot at private facilities. A patient may have to shell out around Rs 8 lakh for standard breast cancer surgery in a private hospital. At AIIMS, this procedure costs around Rs 5,000. Chemotherapy drugs, compared to targeted therapies and immunotherapies, still do not cost a lot,” he says. Then there are PET scans for tracking cancer resurgence every three months. “These cost around Rs 25,000 per session,” says Yamini.

Tests & care protocol: Insurance falls short

The family spent Rs 3 lakh on getting Meenakshi tested for the genetic marker that Osimertinib specifically targets, the epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR), which accelerate tissue growth. To check whether Meenakshi’s cancer was EGFR-positive, her sample was sent to a laboratory in the US. “We are fortunate to have the means but most people are unable to bear the costs of cancer treatment and wait in long queues for months at government centres. Most families, including us, also have to ensure that we do not stretch ourselves too thin. There are other seniors and children in the family who would require healthcare,” says Yamini.

Since targeted therapy is a modern treatment, most insurers fall short of including it in their plans on the ground that it is still in the experimental stage. Few companies with cancer-specific plans may cover it but with sub-limits. “Increasingly, cancer care — including day care treatments — are being covered by insurance providers and government schemes such as CGHS and ECHS. As that goes up, people may be able to spend a bit more on targeted therapy,” says Dr Julka. An extended lifespan, at the moment, seems like an elite privilege.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05