Zubin Mehta on leading the Symphony Orchestra of India, his love for Bombay and Trump’s comments on Gaza

In an exclusive conversation, 88-year-old Zubin Mehta, one of 21th century’s greatest conductors, on returning to the city of his birth and how he will continue to make music for peace.

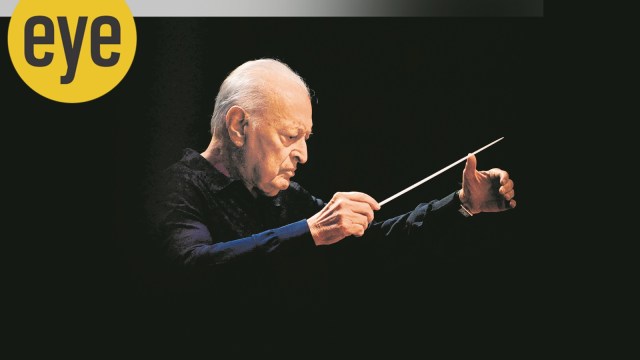

Zubin Mehta at Mumbai’s National Centre for the Performing Arts (Express Photo/Sankhadeep Banerjee)

Zubin Mehta at Mumbai’s National Centre for the Performing Arts (Express Photo/Sankhadeep Banerjee)On a pleasant and breezy February evening in Mumbai, 88-year-old Zubin Mehta, the globally celebrated Indian conductor and, perhaps, the most famous son of ‘Bombay’, seems far away. He is surrounded by a striking vortex of cellos, heaving violins and a sweet singing harp — being tuned for his rehearsals with the Symphony Orchestra of India (SOI) — the country’s first and only professional Western classical orchestra nurtured by and housed at the ocean-facing National Centre of Performing Arts (NCPA) in Mumbai.

We meet him in the green room of Jamshed Bhabha Theatre, not far away from his home — 21 Cuffe Parade — where his father, an accountant-turned-violinist and conductor Mehli Mehta created the Bombay Symphony Orchestra in 1935 and a string quartet in 1940. This is also where Mehta played cricket with his childhood friend and Cipla chairperson Yusuf Hamied, who lived a stone’s throw away. Friends since they were two, the ‘Bombay boys’ still get excited over an excellent cover drive and catch each other around the world over phone to analyse the last cricket match. “Bombay is everything to me. When I am outside, I dream about Bombay. That doesn’t go away, my days here, my friends. It is my love for this city that brings me back,” says Mehta, even though he has become uncomfortable with the city’s changing landscape.

But right before a rehearsal is not the space or time to have a conversation with one of the century’s greatest conductors. Cantankerous and slightly acerbic with tensions of getting everything just right riding on his mind, our visit from Delhi sets him off. “It’s about time that you build a concert hall in Delhi,” he hollers. One can only apologise on Delhi’s behalf and agree with him on the Capital’s lack of a concert hall with good acoustics. Right then, despair makes its way: “I have spoken to so many ministers of culture. They all agree, but they don’t do anything. They need to build a concert hall in the capital of one of the largest countries. I performed at Siri Fort, it was terrible,” says Mehta.

It has taken Mehta almost a lifetime on the podium to finally find the confidence and comfort to conduct 18-year-old Symphony Orchestra of India. India has her own music and western classical music never found as much attention in the past. Mehta feels that SOI was more of a creative mind block for him as he had never heard them before. It was almost a decade ago that the NCPA chairperson Khushroo Suntook — who went to school with Mehta at Campion School in the ’40s — set out to draw his friend back home, “to see the work that was being done here”. Mehta finally agreed to visit in 2023 and decided to do what he’d never done before — conduct India’s only Western classical orchestra.

“They surprised me when I first came in 2023. The standard of the orchestra was way more than I had expected,” says Mehta. So much so that he has returned to perform with them again only after a five-month gap (he was here in August 2024). This time, besides interpretations of Mahler and Chopin — Mehta also presented excerpts from two famous operas — Carmen and La Traviata.

Mehta, who still uses Bombay, the colonial moniker to address the city of his birth, has always been upfront about his perspective on the quality of the musicians he works with. In a stellar career that spans over half a century, Mehta has almost always found admiration for his earnest, unequivocal music presentations in the melodically magnificent Viennese style, while recreating the music of the Romantic era’s greatest names, including Beethoven, Tchaikovsky and one of his absolute favourites, Gustav Mahler.

Mehta has also, more often than not, been vocal and upfront about his perspective on the politics of Western Asia; probably a result of his association with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, of which he is a conductor for life, and spending a considerable amount of time in the country he considers his second home.

His face, with a filigree of lines, has aged, his back has stooped, and he needs a wheelchair and a walking stick to find his way around but talk to him about his music, his childhood, his favourite scores, the most memorable concerts, and Mehta perks up, finding everything in him to tell you stories of his life, ones that are also, in a way, stories of the world.

Mehta at the rehearsal with members of the Symphony Orchestra of India (Credit: NCPA)

Mehta at the rehearsal with members of the Symphony Orchestra of India (Credit: NCPA)

Mehta does not remember the first time he heard music. “Music was probably my first language. I knew it even before I knew how to speak Gujarati,” says Mehta, who is also fluent in German and Yiddish.

Mehta’s father possessed a large collection of one-sided, bad-quality 78 RPMs and he soon became familiar with a variety of Western music. While the music wasn’t as clear, the tempo is what Mehta imbibed. Rhythm still remains Mehta’s stronghold. Then there was music from his living room, where his father’s Bombay String Quartet rehearsed. “He was Mr Music in Bombay, a brilliant musician,” he says.

Mehli was a self-taught violinist, whose family wasn’t happy with him being a musician. “It wasn’t respectable then,” says Mehta. He went to Sydenham College for a degree in commerce, played cricket with Vijay Merchant and was employed as a tax collector for the government before he decided to give up everything to live his dream of being a musician. Mehli also took up a job at All India Radio and in 1936 played Walter Kaufmann’s signature violin tune that opened the broadcast every day. He moved to the US through a Tata grant to study music and returned in 1949. He still remains a key influence on Mehta and towers above every piece Mehta plays.

Mehta’s mother Tehmina and her family were not keen that Mehta take up music either. While Mehli taught him the violin, he had to join St Xavier’s College to pursue medicine. “It wasn’t for me,” he says. One of his cousins was learning to play the piano in Vienna and offered to support Mehta, who was now learning music theory from his physics teacher, the pupil of a well-known Spanish composer of the time. Mehta moved in 1954 to Vienna, a city wounded by war and heard the Vienna Philharmonic for the first time. “Oh! It was an audio revolution. I had only heard this one orchestra in Bombay or records with lousy sound. Hearing the Vienna Philharmonic was a complete revelation. And then that became my axiom,” says Mehta, about the warm timbre of the Viennese style that never sounded too sparkly. The Academy of Music at Vienna, Mehta has often said, taught him his whole concept of sound. “I tried to emulate that Vienna sound when I first went to Montreal, and later in Los Angeles. I also made them buy Viennese instruments,” says Mehta.

Mehta was clear that the violin or the double bass that he could play was not something he considered his future. It was conducting, and the air of enigma around it, that had him hooked. “Conducting is communication. We have to communicate the message of the great composers that we supposedly interpret. Every conductor has their own way,” says Mehta, who learned from his teacher Hans Swarowsky that it’s the wrist and not the arm where the magic lies. He conducted one of his first concerts at a refugee camp outside Vienna with seven students soon after the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

In 1958, he married Carmen Lasky, a Canadian music student in Vienna. They had two children but were divorced in 1964. Lasky later married his brother Zarin while Mehta married actor Nancy Kovack in 1969.

It was in 1961 that he first conducted the Vienna Philharmonic and became its youngest conductor at 25. He’s returned every year since. “It (the Golden Hall at the Musikverein) is the best concert hall in the world,” he says. After his seven years in Vienna, Mehta was the music director of Montreal Symphony Orchestra followed by Los Angeles Philharmonic and New York Philharmonic. A brown boy conducting European music with some brutal charm had a generation confounded all over the world. Mehta believes he never really felt any discrimination on the basis of race or colour, except perhaps in Liverpool. The appreciation elsewhere was going to superlatives. Josef Krips, the conductor of San Francisco Philharmonic said once, “The next Toscanini has been born!” “Musicians play well for him, because they like him,” The New Yorker wrote in 1967. Mehta was 31 then. He came with a distinct ability to gauge the audience as well as the musicians, who under his baton would punch above their weight. He heard them and they heard him back, creating a synergy that showed on stage.

But his longest and most-talked about association has been with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra — Israel’s premier cultural export to the world — in Tel Aviv, which is when his progressive political views, which he’s always called “musician’s opinion”, came under the spotlight. Mehta has done over 5,000 concerts with the Orchestra, performing in countries where Israel has not been welcome politically. “And yet they gave us a standing ovation. This is not easy,” he says.

That said, he’s been vocal about not supporting Israel’s occupation of Palestine in the past. He stood up for Argentina-born Israeli conductor, pianist and his friend Daniel Barenboim, disapproving of Israeli lawmakers who banned performances by Barenboim. They were unhappy about him performing compositions by German composer Richard Wagner, whose perception has been denigrated due to his connections with Nazism and also because he was Hitler’s favourite composer. Mehta has often visited Ramallah in Palestine and has worked with Arabic musicians, in the hope that the orchestra, one day, will have artistes from both communities.

In 1971, Mehta performed in Berlin with the Israel Philharmonic. Just after the concert where they played Jewish composers had ended, he took a bow and led the orchestra through Israel’s national anthem. Barely half a kilometre away from the Reichstag, once the National Parliament of Nazi Germany, a musician had found a way to alter the rules, finding a greater purpose than just pleasing an audience. It was political. People wept. It also remains his most memorable performance.

On another occasion when Israel was at war with Lebanon in 1982, Mehta, with the help of Israeli police, took the orchestra to a tobacco field, just across the border in Lebanon and performed on a makeshift stage under a tent. Then there were free concerts in Israel during the Gulf War in the mornings, as evenings were lights-out to stave off missiles by Saddam Hussein’s Iraq or the iconic performance at Sarajevo in 1994, where he performed at the bombed site after the Bosnian war. His belief that artistes are more than entertainers has stood tall for decades. He also performed in Israel in February 2024 during the war between Israel and Hamas amid the massive geopolitical crisis, hoping that the power of music can bring peace to the region. “The halls were full. People need music. How do they live without it,” says Mehta.

With a fragile ceasefire between Israel and Hamas underway, American President Donald Trump’s comments where he wants to “take over” and “own” Gaza have bothered Mehta. Since his ‘proposal’, which has drawn flak from the UN as well as many US allies, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has welcomed his “revolutionary vision” for Gaza. It has upset Mehta to no end. “There are still religious people in Israel who agree with him. I don’t think it will ever happen,” says Mehta.

But, will Wagner ever be played in Israel — something he last tried in 1981 which led to protests — he says, “Some day”. “They don’t want to be transported back to the days of terror. One can understand that,” says Mehta, who after Mumbai is headed to China for eight concerts. “In November, I will be in Israel,” he says. In his 60s, he’d say, ‘I’ll rest and retire when I get old’. In his 80s, he continues to adore his vocation — that excruciating, physically tiring interpretation of great music. What’s compelling is that even after all these years, when he explores Mahler’s First or Chopin’s Concerto in F Minor, he still falls in love with it. “That’s why I do it. That’s why I’ll keep doing it,” he says.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05