Krishnendu Bose’s Bay of Blood recounts carnage of Pakistan’s Operation Searchlight on Bangladesh

The documentary traces how the Pakistani Armed Forces, under the command of the then-President General Yahya Khan, initiated Operation Searchlight in March 1971, a campaign of torture killings and rape to erase Bengali resistance.

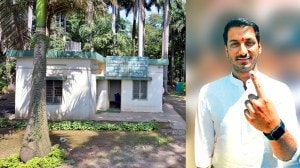

Krishnendu Bose (left) during the recording of Bay of Blood.

Krishnendu Bose (left) during the recording of Bay of Blood. On February 26, 1971, Raqibul Hasan, the benchwarmer for the Pakistan cricket team, was finally stepping out to bat against the Commonwealth side at Dhaka’s Bangabandhu Stadium. All of 18, and the only player from East Pakistan in the team, he reached the striker’s end, and with a glint in his eye, revealed a curious sticker on his bat — the words “Joy Bangla” written in Bengali. In a euphoric flash, the audience erupted in loud chants of the familiar war cry, resulting in disruptions to the game, which was cancelled. Little did Hasan know at the time that he would be “giving up the bat and picking up the Sten gun” to fight for the liberation of his country.

“Joy Bangla” was the war cry of the Mukti Bahini, a guerrilla resistance movement of military and civilian forces, fighting for the freedom of Bangladesh. Hasan narrates this story in Bay of Blood, a documentary by Delhi-based filmmaker Krishnendu Bose that was recently screened at the India Habitat Centre.

The Pakistani Armed Forces, under the command of the then-President General Yahya Khan, initiated Operation Searchlight in March 1971, a campaign of torture killings and rape to erase Bengali resistance. While the exact death toll is debated, independent researchers have pegged it at nearly three million people during the nine-month exercise. The operation was a result of years of cultural subjugation of the Bengali identity, including the Bengali language, and even discrediting a general election where the Awami League, a Bengali nationalist party of East Pakistan, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, won by a majority. The film is a haunting retelling of the events leading up to West Pakistan’s Operation Searchlight and the subsequent carnage and fight for independence.

A fatwa was issued during the Operation that declared women as “booty of war”, which led to 200,000 cases of systematic rape, according to independent researchers. Pakistan Army soldiers captured numerous women and kept them as sex slaves. One of the rape survivors, who recalled the dreadful day in the film, says, “A Pakistan Army general was ‘compassionate’ for not capturing me and instead instructed his troops to commit the horrific act at my home. My infant son, who saw the act, died of shock on that day.” The film was structured as a deposition, where each contributor walked into the studio, sat on the chair and told their story. “The sources were authenticated by triangulating information, and only then were the stories presented,” says Bose.

A poster of the film.

A poster of the film.

This process is captured by stories of witnesses, Pakistani and Bangladeshi journalists, freedom fighters, writers, academics, defectors and American diplomats. In the film, Scott Butcher, ex-US Foreign Service, who worked in Dhaka in 1971, recalls the then American Consul General to Dhaka, Archer Blood’s ‘Blood Telegram’, where the latter expressed his dissent in the way the White House responded to Pakistan’s attack on Bangladesh. “What we were witnessing was definitely a genocide,” says Butcher, in the film.

Bay of Blood uses archival footage, coupled with colour-treated shots of present-day Bangladesh and juxtaposed with the chilling narrations of the horrors of the atrocities, to bring to life the dark time that the country had to go through. Bose also got footage from international news agencies such as BBC and Associated Press, the Bangladesh Liberation War Museum and the National Film Development Corporation. The filmmaker says he had to brainstorm with his editor David Fairhead and the director of photography Jeremy Jeffs to come up with a linear objective narrative for the documentary.

Bose had earlier made several award-winning films on wildlife conservation and environmental justice. Visiting Kolkata as a boy of 10, Bose recalls witnessing a large influx of people coming from the neighbouring country. Like many Bengalis, he too learnt of the dark time through books, including Salil Tripathi’s The Colonel Who Would Never Repent (2014), Garry Bass’s The Blood Telegram (2013), and Srinath Raghavan’s 1971 (2013). Fast forward to 2019, the filmmaker decided to revisit the past.

“The two rape survivors who we interviewed, travelled six hours from their village to Dhaka just to tell their story. When we were filming in Washington, a Bangladeshi American, who had moderate means, travelled all the way from New York. I asked him how much we owe him for the commute and he said, ‘If you can do so much for my country, why can’t I do this little thing?,” says Bose.

The recently released White House tapes of former US President Richard Nixon and the then Secretary of State Henry Kissinger provided Bose clues into the events leading up to the genocide. “Who were the perpetrators and why were they doing it? This story had global players like Nixon, Kissinger, Yahya Khan, Mujibur Rahman and Indira Gandhi. There’s China, Russia and the Cold War, which were pertinent to the events leading up to the genocide. What does all of this have to do with Bangladesh — some small little country in the Bay of Bengal? These are important questions. The world is on the verge of this kind of situation even today,” he says.

“My wife and co-producer of the film, Madhurima, whose family also hails from Bangladesh, egged me on to explore this story. I travelled to Bangladesh, interviewed a few people and made a short 10-minute promo of the film, which I showed to TV channel representatives at annual television market events in Cannes, France and Singapore. They had no idea (of the genocide) and that shocked me and gave me the determination to make this film and tell the story to the world,” he says.

Around fifty years after the horrific event, Bose believes that the story is happening right now, across the world. “Suppression of democracy, people, crimes against humanity and even genocides are happening but are not recognised or being talked about. Some of the players of this 1971 genocide could be the same today. The weapons may be more sophisticated but the power blocks are the same. My intention for making this film was to tell the story, surely of 1971, but also to learn. We haven’t learned in the 75 years of the Holocaust. We need to remember that this needs to stop and recognise that this could be happening in your backyard, probably right in front of your eyes. It’s a very livewire story of our times,” he adds.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05