What makes Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam a name that worries the powerful elite

In this interview, Alam speaks about the repressive terrain in his country, his first retrospective in Asia, his days in jail and what will worry him the most

Shahidul Alam (Photo credit: Rahnuma Ahmed)

Shahidul Alam (Photo credit: Rahnuma Ahmed)Your exhibition “Singed but not burnt” at Emami Art, Kolkata (curated by Ina Puri, on till August 20), documents the shift from early photorealistic images to documentary work, evident in the series such as “Crossfire” (2010), on extra-judicial executions in Bangladesh. Can you talk about your work that straddles art and activism?

I have developed a visual vocabulary where politics cannot be disengaged from my art. Photography’s ability to provide information was not what was needed in the case of “Crossfire”. The story was known. The need was to build resistance, to shake people, to get under their skin, and to challenge a repressive regime. Creating a tangible link to the moment of death, I felt, would evoke a much more powerful response. It was confirmed not only by how people responded to the work but also how fearful the terror squad, Rapid Action Battalion, was of the show itself.

Student in Prison Van by Shahidul Alam (1996, Dhaka) (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

Student in Prison Van by Shahidul Alam (1996, Dhaka) (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

You started photography as a chemistry doctoral student in London, when a friend could not reimburse you for a Nikon FM you had bought for him in 1980. If you could tell us more.

It was a happy accident. It was my association with the Socialist Workers Party and seeing how effectively they used photography in their campaigns that made me decide to take up the medium. Never having had formal training, my major influences were camera clubs and popular photography magazines. But while creating pretty pictures is no longer the point of the exercise, using aesthetics as a visual tool is a strategy I still find useful.

In the 1980s, you left London and moved to Dhaka to pursue photography. You established a conducive ecosystem through initiatives like Drik Picture Library, Pathshala (photography school), Chobi Mela (Asia’s first international photography festival).

Setting up an agency in the commercial centres of photography in Paris, London or New York, was never going to help Bangladeshi photographers. If we want to serve local photographers, we need to be where they are, speak their language, and understand their concerns. As for Pathshala, you can’t fight a war without warriors. One of Pathshala’s tutors called the students photo militants fighting for justice. Chobi Mela served two purposes. It introduced our warriors to cutting-edge work and to practitioners from across the globe, which was needed if they were to hold their own on the global stage.

Solidarność Movement by Shahidul Alam (1981, UK) (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

Solidarność Movement by Shahidul Alam (1981, UK) (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

From capturing protests to the first elections after military rule, how has it been to photograph democracy in Bangladesh?

We’ve never really had democratic practice in Bangladesh, so repression of one form or another is what I’ve always been faced with. That is what I’ve questioned and why I’ve always angered the powerful elite. I first showed “A Struggle for Democracy” during General Hussain Muhammad Ershad in the 1980s. I sent an open letter of protest to the prime minister, against the muzzling of the media during BNP (Bangladesh Nationalist Party) rule in 1992. I showed “Crossfire”, the Kalpana Chakma trilogy, and reported on the attack on student protests during the Awami League rule. Consequently, I’ve had a gun held to my head during the Ershad regime, received eight knife wounds during the BNP regime, and this government tortured me and put me in jail and still has a case hanging over me. That’s the terrain I work in. It’s when the government starts giving me plots of land and invites me to PR exercises and paid junkets that I’ll start worrying I’m doing something wrong.

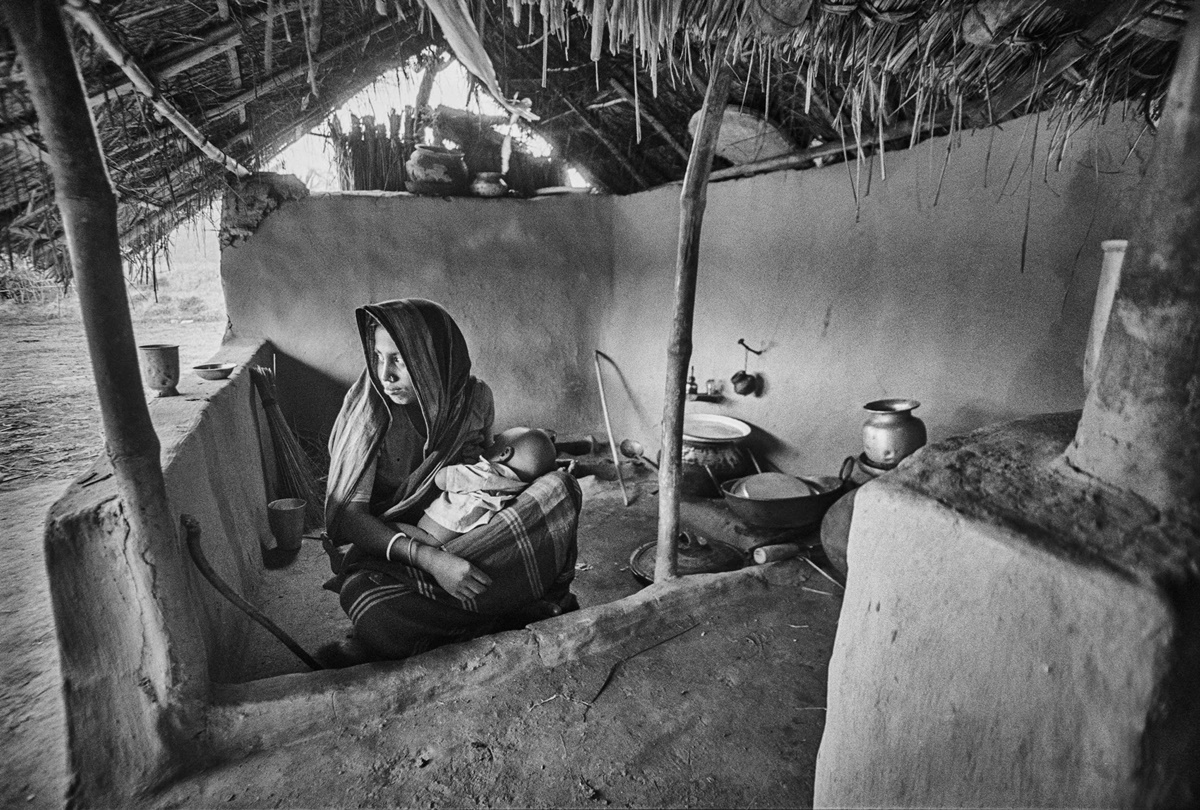

Rural Kitchen by Shahidul Alam (1992, Bangladesh) (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

Rural Kitchen by Shahidul Alam (1992, Bangladesh) (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

Sociopolitical concerns often emerge in your works. Can you talk about some of them?

Much of global wealth has been built through the exploitation of migrant workers. New forms of slavery continue to enrich wealthy nations of today. Some 3,500 bodies of young migrants, mostly men in their prime, return as corpses to Bangladesh every year. No one is held accountable for this mass murder. Some 3,500 bodies of young migrants, mostly men in their prime, return as corpses to Bangladesh every year. My work on migration is a story I’ve been working on for nearly 30 years. Sadly, while the work (Migrant Soul) has received appreciation, it hasn’t really resulted in a change in the lives of migrant workers.

Buy Now | Our best subscription plan now has a special price

“Embracing the Other” (2017) was produced to support a campaign for the Freedom of Religion or Belief, where I remain active. Islamophobia in India and the West has led to internal strife and the ruination of Iraq, Yemen and many other countries. Palestinian lives continue to be squandered in the face of illegal occupation, while the most powerful nations look the other way.

Woman in Ballot Booth by Shahidul Alam (1991, Dhaka) (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

Woman in Ballot Booth by Shahidul Alam (1991, Dhaka) (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

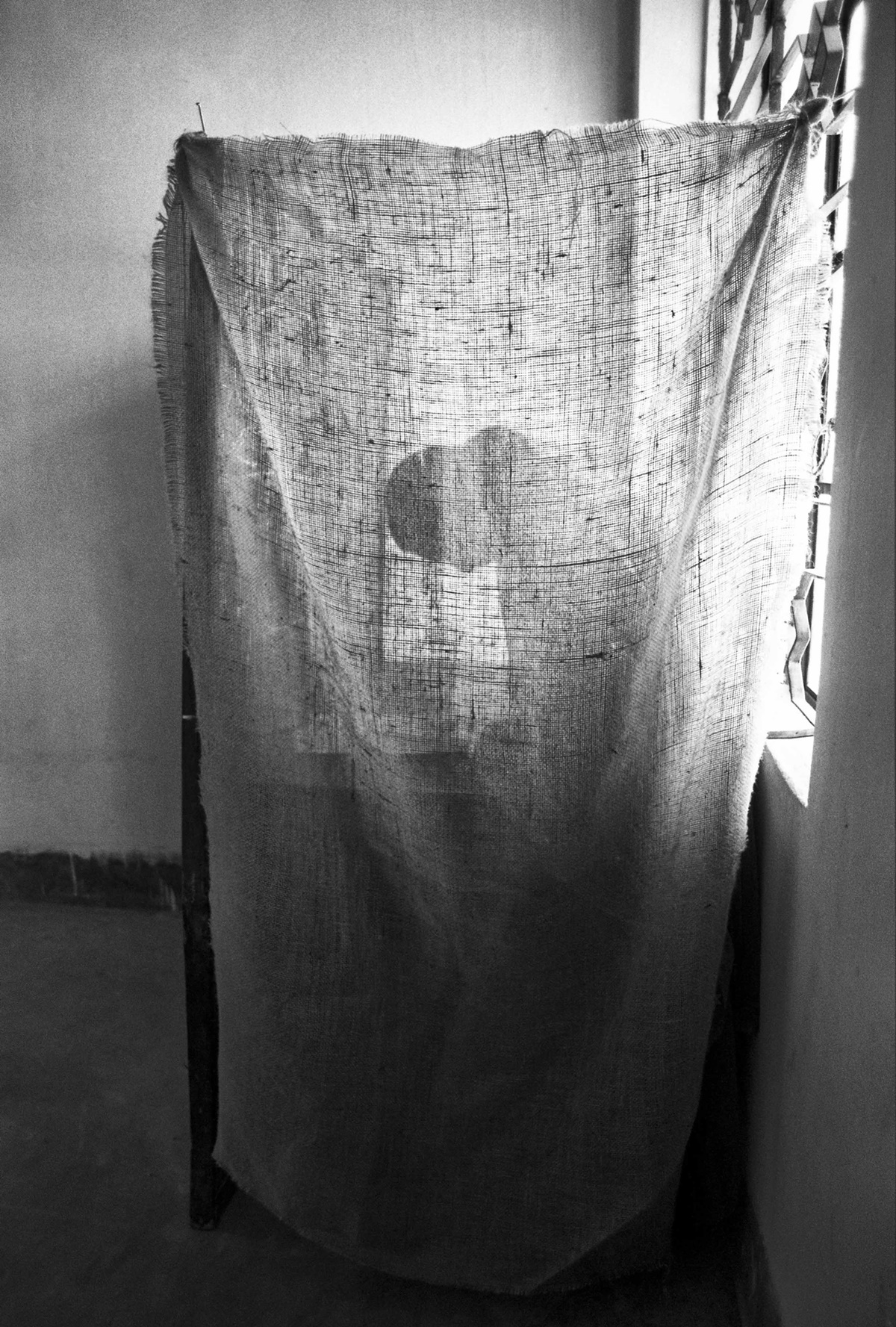

Through the series “Kalpana’s Warriors” you tell not just the story of the indigenous rights activist (who was abducted at gunpoint in 1996 and has not been seen since), but also of Bangladeshi campaigners who were silenced. Could you tell us about the project?

The need to speak our own language was the central argument behind the liberation of Bangladesh in 1971. Yet in our own land we refuse others the right to speak theirs and subject them to military occupation. The abduction of Kalpana Chakma is a shameful act of state brutality. The inability to bring the perpetrators to justice leaves the darkest stain on our Judiciary and our Executive. Through the exhibits, I’ve tried to interrogate the silent witnesses at the scene of the crime, humanise a revolutionary that the state has tried to demonise, and celebrate the warriors who still campaign for her justice.

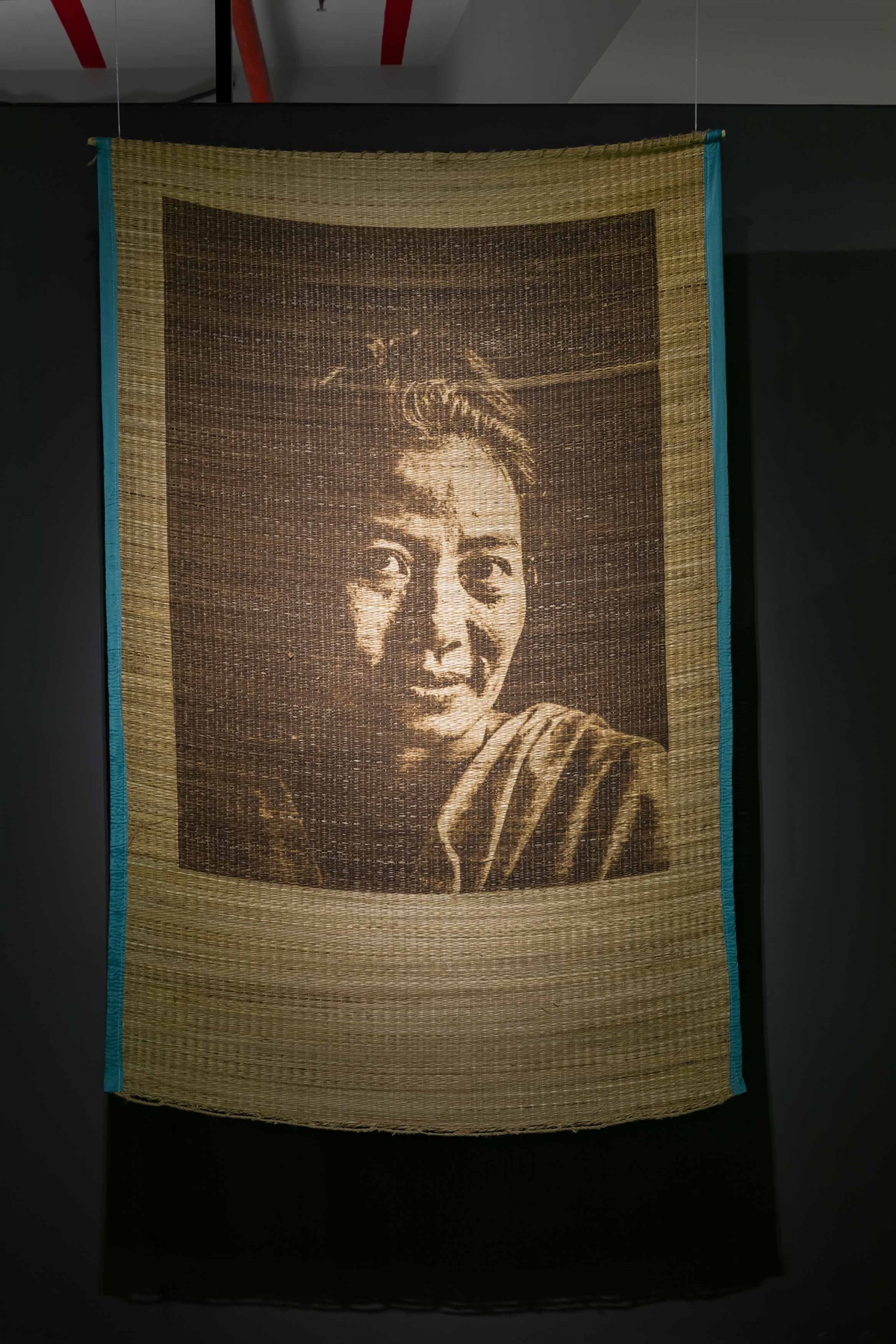

Portrait of Samari Chakma from the Kalpana Warrior series, laser etching on straw (2015, Dhaka) (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

Portrait of Samari Chakma from the Kalpana Warrior series, laser etching on straw (2015, Dhaka) (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

Through all this, how do you negotiate the interfaces with power?

I am part of a team and the biggest danger when you face repression is the situation of the most vulnerable. They risk a lot more than I do, and not all of them signed up for a life of activism. I am hugely grateful that they have stayed with us through these difficult times.

That China can order the closure of a show in Bangladesh (when the police disallowed Drik from opening the exhibition “Into Exile: Tibet 1949 – 2009”) that is critical of their regime, should be a wake-up call to our citizens. It is a sign of how spineless our government has become. Mahasweta Devi, one of the most respected citizens of our region, being denied access to our gallery (to inaugurate Crossfire in 2010), is a sign of how our value system has been eroded.

So the Shilpakala Padak (in 2015) was a surprise, as these awards are generally reserved for party cronies. I constantly remind my students that producing bloody good work, consistently and relentlessly, is an artist’s best defense.

Floating forest, Kew Gardens, London, 1983. (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

Floating forest, Kew Gardens, London, 1983. (Photo credit: Emami Art, Kolkata)

In 2018, did you anticipate that you could be arrested for supporting the student’s protest demanding road safety in Bangladesh? Also, what kept you engaged in jail?

I was also attacked the day before, on August 4, 2018, when my equipment was smashed. So, the possibility of being picked up was always there, but while I knew the risks, I hadn’t anticipated that they had such poor judgement. My immediate instinct was to try to stay alive and I did whatever I could to slow down my arrest and to make sure that others knew I was being taken away.

The support from my Indian friends and colleagues was incredible. Fellow prisoners sneaked in the letter Raghu Rai had written to our prime minister, and I read the letter Arundhati Roy wrote on my 100th day of incarceration. Amartya Sen and other Nobel Laureates joining the campaign for my release meant so much to all of us.

In jail, I read voraciously. I interviewed people I would normally not have had access to. I worked with fellow prisoners to paint murals across the jail. We set up a musical band, adult literacy classes and started a vegetable patch. I certainly wasn’t the only one involved, but between us, I believe we were able to transform the place. I remain involved in prison welfare.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05