100 Years of Talat Mahmood: The story of the man with a silken voice

In his centenary year, remembering playback legend Talat Mahmood, whose voice remains a salve for the broken-hearted.

In his centenary year, remembering playback legend Talat Mahmood, whose voice remains a salve for the broken-hearted

In his centenary year, remembering playback legend Talat Mahmood, whose voice remains a salve for the broken-heartedKarachi-based Zaheer Alam Kidvai, 84, was seven when his father, a Delhi-based doctor in the Army, decided to leave for Pakistan in the aftermath of the Partition. Before migrating from Bombay to Karachi via boat, the family boarded a train from Calcutta to Bombay. “My father’s youngest cousin, Talat Mahmood, the great playback singer, also came to see us off. When people saw him, they rushed towards him… As we boarded the train, we heard people shout, ‘This is Talat Mahmood! He is going to migrate, hold him!’,” recalls Kidwai in a conversation mentioned in the ‘1947 Partition Archive’, an online document that chronicles lives shaped by Partition.

But Talat wasn’t going anywhere. He had decided to stay back despite most of his family and friends crossing the border, only months after Calcutta, the city he lived in, witnessed the communal riots of 1946 which killed thousands and left the streets strewn with bodies as vultures famously feasted on them. After all, this was the city that had given him his first taste of success — as a ghazal star and as a playback singer.

“There was a lot of respect for his gentle, velvety voice. It was and remains distinct because it came with the Lucknowi tehzeeb and sounded, for the lack of a better word, sophisticated. The concept of ‘pehle aap’ dripped from that singing voice. For several music connoisseurs, it still remains soul-stirring,” says film music historian Manek Premchand, who also penned the singers’s biography, Talat Mahmood, The Velvet Voice (Manipal University Press) in 2015.

Ghazal singer Talat Mahmood. (Photo: Express Archives)

Ghazal singer Talat Mahmood. (Photo: Express Archives)

The golden era of Hindi film music turned playback singers — extremely skilled artistes — into superstars. If there was the brilliant baritone of KL Saigal on one side, many fell into worshipful silence listening to Lata Mangeshkar. While most male singers of the day, including Talat, began by imitating Saigal, it was his unique texture and tranquil singing that made Talat a household name. Many of his songs were complex and high-pitched but none ever sounded shrill or pedestrian. They were just right —balanced and elegant, turning him into a master of the ghazal.

Be it a lover’s longing in Seene mein sulagte hain armaan in the Dilip Kumar-Madhubala starrer Tarana (1951), the vagaries of the world philosophised by Shailendra in Aye mere dil kahin aur chal picturised on a drunk Dilip Kumar in Daag (1952), SD Burman’s delicate Jalte hain jiske liye in Bimal Roy’s Sujata (1959), and the plaintive Shaam-e-gham ki qasam — a masterstroke by writer Majrooh Sultanpuri and composer Khyyam in Footpath (1953) — Talat’s voice, with its immaculate diction, was warmth, melancholy and intimacy all rolled into one. “It felt as if he was singing only for you. The voice was distinct also because it came from a compassionate, genuine person,” says Sahar Zaman, Talat’s grand-niece, who recently released her book, Talat Mahmood: The Definitive Biography, to coincide with his centenary. One may think that the 750 songs in 12 languages that he left behind when he passed away in 1998, aren’t in circulation anymore if not forgotten. But Zaman disagrees. She recently came across a European website selling merchandise that said: ‘I don’t need a therapist because I have Talat Mahmood’.

****

Born in a conservative family in Lucknow that appreciated music and Urdu poetry, Talat was the third among six siblings. His father, a Gandhian, owned a curio shop in the city’s bustling Aminabad. While Talat had access to music, his understanding of it, as he said in his interviews with Premchand, came from the time he spent with his aunt (father’s sister) Mahlaqa Begum, a writer and connoisseur of music, who would often host musical baithaks in her courtyard. While Talat’s father appreciated art and culture, he didn’t want his ‘khandaani beta’ to sing professionally. But Mahlaqa Begum persuaded her brother to send Talat to Lucknow’s Marris College of Music, which is now Bhatkhande Sanskriti Vishwavidyalaya, on the condition that he would only learn. At 16, Talat tried his luck at All India Radio, where after six months of training, he began to sing Ghalib and Mir’s poetry.

Around the same time, HMV was scouting for a new voice and selected Talat from his college to record in Calcutta in 1941. He recorded three ghazals with composer Kamal Dasgupta. This is when composer and actor Pankaj Mullick offered Talat a contract with the famed New Theatre Productions.

Anil Biswas and Lata Mangeshkar with Talat Mahmood. (Photo: talatmahmood.net)

Anil Biswas and Lata Mangeshkar with Talat Mahmood. (Photo: talatmahmood.net)

But a 17-year-old Talat asked for three more years to complete his music education. Success came in 1944 with the runaway hit Tasveer teri dil mera, a piece composed by Dasgupta and penned by Fayyaz Hashmi, most remembered for his famed ghazal, Aaj jaane ki zid na karo. Impressed by the honeyed voice and figuring that it would suit the cadence of Bangla, Mullick asked Talat to sing in Bengali. This is when Bengali singer Tapan Kumar was born. While he sang his Hindi songs as Talat Mahmood, Bengali records came under the name Tapan Kumar. “His Bangla diction was so spot on, that many people thought that he is a Probashi Bengali who uses the name Talat Mahmood for his Hindi numbers,” says Zaman. This was also when he fell in love and married Latika Mullick, a Bengali Christian actor. Talat’s father remained unhappy with his commercial singing but accepted the hushed wedding.

At New Theatres, Talat’s good looks and immaculate dressing (always suit and tie), besides his polite, Lucknawi tehzeeb and quiet demeanour led to acting assignments. His first was PC Barua’s Rajalakshmi (1945) followed by 11 others. But besides Sone ki Chidiya which happened later in 1958 and starred Nutan alongside, nothing caught people’s eye. The voice, however, kept finding much attention and affection from those who heard and became extremely moving for the ones who really listened.

Ghazal singer Talat Mahmood. (Photo: Express Archives)

Ghazal singer Talat Mahmood. (Photo: Express Archives)

***

The Partition and the formation of East Pakistan massively affected the film industry in Calcutta. Talat’s acting career, too, was tanking. This is when he decided to move to Bombay. Here he met noted composer Anil Biswas who had heard his Bengali songs and gave him one of his career’s biggest hits – the pathos-laden Aye dil mujhe aisi jagah le chal in Arzoo (1950), a film that was based on Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. Biswas was impressed with the tremolo effect, the quiver that made Talat unique and according to Biswas, “hard to copy”. Picturised on Dilip Kumar, the pain in the song, of not being able to be with one’s beloved, is palpable as Talat sings Duniyaa mujhe dhudhe magar, Meraa nishaa koi na ho.

Arzoo’s success was followed by Milte hi aankhen dil huya with Naushad in Babul (1950). The ’50s threw up some brilliant gems such as Meri yaad mein (Madhosh, 1951) and Seene mein sulagte hain armaan. Talat’s fascination for Urdu poetry also drew ghazal king Madan Mohan to him. The two recorded 23 songs together, including the famed Phir wohi shaam (Jahan Ara, 1964), every intricacy sounding effortless. Talat’s stardom was at an all-time high for straight 15 years of the golden era. Premchand corroborates the stories of women writing letters in blood and lining up outside his house in Bandra to get a glimpse of him. His fans also included Mehdi Hassan and a young Jagjit Singh, who often spoke of learning from his records back in their respective Punjabs, harbouring dreams of singing like him one day.

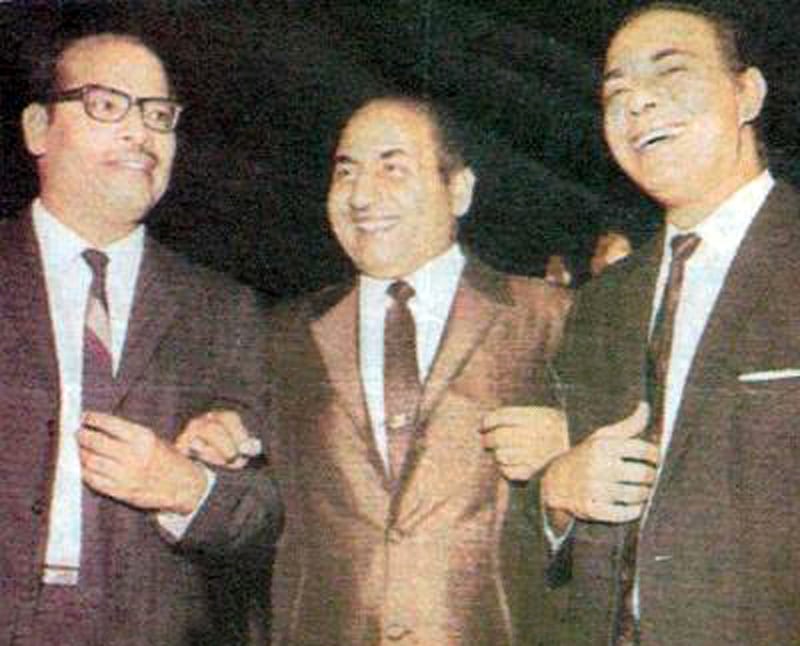

Manna Dey and Mohammed Rafi with Talat Mahmood. (Photo: talatmahmood.net)

Manna Dey and Mohammed Rafi with Talat Mahmood. (Photo: talatmahmood.net)

Around the same time, singers Mukesh and Mohammad Rafi were finding box-office success. There was also an advent of Western sounds in Hindi cinema and a change of pace by composers such as OP Nayyar, who included a lot of Punjabi elements. This was a departure from Talat’s polished style.

“Versatility was an issue. Rafi is considered a greater singer in terms of range, quantity and versatility,” says Premchand. At this time, even though fewer songs came to Talat, Salil Chowdhury asked him to croon for Bimal Roy’s Madhumati (1958). But at the time, his friend and singer Mukesh was going through financial troubles and Talat asked for the project to be given to him. One wonders how Suhana safar aur ye mausam haseen would’ve sounded in Talat’s voice, had he taken up the film. In these years, Talat also led the three-month collective mic-down protest on the royalty rights of the singers as Secretary of the Playback Singers Association.

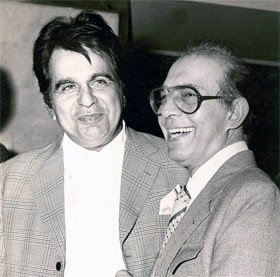

Dilip Kumar with Talat Mahmood. (Photo: talatmahmood.net)

Dilip Kumar with Talat Mahmood. (Photo: talatmahmood.net)

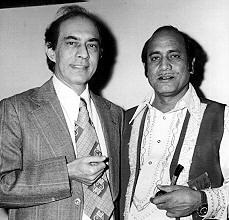

Talat Mahmood with Mehdi Hassan. (Photo: talatmahmood.net)

Talat Mahmood with Mehdi Hassan. (Photo: talatmahmood.net)

But as his film career slid, Talat began doing live shows globally, one of the first playback singers to do so. He was immensely successful till 1992, the last year that he performed. He was given a Padma Bhushan in the same year for his service to the country and passed away in 1998 due to a cardiac arrest. He was 74 and left behind a lasting legacy, songs which still have that transcendental effect and remain etched in memory. “There have been many singers, but there was only one Talat,” says Premchand.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05