Why Sylheti is not a ‘Bangladeshi language’

Some seven million people in the North East speak Sylheti, many of whom have been living in present-day India well before East Pakistan, let alone Bangladesh, was even imagined.

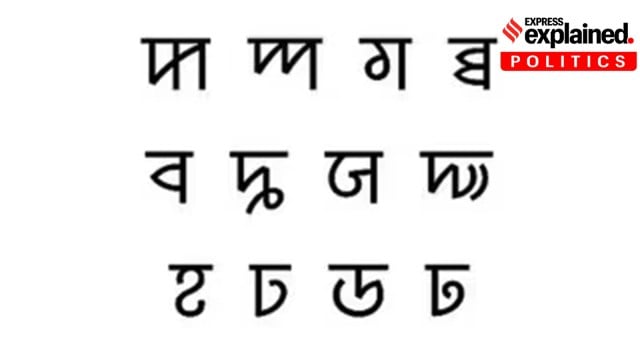

Sylheti script. (Source Wikipedia)

Sylheti script. (Source Wikipedia)Amid a roiling controversy triggered by a Delhi Police letter seemingly referring to Bengali as the “Bangladeshi national language,” a social media post by BJP leader Amit Malviya has sparked an outcry in Assam’s Barak Valley.

In his defence of the letter, Malviya claimed it was referring to “a set of dialects, syntax, and speech patterns that are distinctly different from the Bangla spoken in India”, and gave the example of “Sylhelti” as being “nearly incomprehensible to Indian Bengalis”.

What is Sylheti? What is the history of its speakers? And why have Malviya’s comments touched a raw nerve in Assam?

Dialect or language?

Sylheti is spoken on both sides of the border, in the Sylhet Division of Bangladesh as well as the Barak Valley Division of southern Assam. There is also a sizable presence of Sylheti-speakers in neighbouring Meghalaya and Tripura.

“Every language has dialects and Bengali has several of them,” said Joydeep Biswas, who teaches economics in Cachar College.

The primary argument for referring to Sylheti as a dialect of Bengali — and not a language in its own right — is mutual intelligibility, that is, speakers of both tongues understand each other. However, there is scholarly disagreement on the matter.

“The claim of mutual intelligibility by some speakers of both Sylheti and Bengali may be more an effect of the speakers’ exposure to both languages,” linguists Candide Simard, Sarah M Dopierala, and E Marie Thaut wrote in their paper ‘Introducing the Sylheti language and its speakers’ (2020).

“Sylheti-speaking areas of Bangladesh and India are characterised by diglossia, where standard Bengali is the language of education and literacy and Sylheti is the vernacular variety used in everyday interactions,” the linguists wrote.

Map of Sylhet

Map of Sylhet

Speakers on both sides of the border nonetheless have a strong affinity to the Bengali language, and often identify as Bengali themselves.

“Families such as mine also speak Sylheti. But I identify my linguistic identity as Bengali because Sylheti is a dialect. Even if non-Sylhetis do not understand Sylheti, that doesn’t take away the [Bengali] linguistic identity of the Sylheti people,” Biswas said.

Tapodhir Bhattacharjee, a former vice-chancellor of Assam University Silchar and a Bengali literary theorist, said that the primary difference between the Sylheti dialect and standardised Bengali is phonetic, while the two are almost identical in morphology and syntax.

While Bhattacharjee recognises that there was once a Sylhet-Nagri script — the existence of a unique system of writing is often seen as a marker of a language — he refers to it as an “esoteric script”.

“It was never a common script used by all. It came into existence in the late medieval ages in Muslim society due to Persian influence. It was mostly used by Sufi fakirs in texts to express their mystic approach towards the Almighty,” he said.

Sylhet, Partition & migration

Historian Ashfaque Hossain refers to Sylhet as historically being “a frontier of Bengal”.

The present-day Sylhet Division in Bangladesh, comprising the districts of Habibganj, Sunamganj, Sylhet, and Moulvibazar, was made a part of Assam soon after it was split from Bengal in 1874.

“Although vast in area, this new province [Assam], with its population of 2.4 million, had a low revenue potential… To make it financially viable… [the British] decided in September 1874 to annex the Bengali-speaking and populous district of Sylhet. With its population of 1.7 million, Sylhet had been historically an integral part of Bengal,” Hossain wrote in ‘The Making and Unmaking of Assam-Bengal Borders and the Sylhet Referendum’ (2013).

Geographically contiguous with Cachar in the Bengali-majority Barak Valley, between 1874 and 1947, Sylhet witnessed a sustained churn over the question of whether it should be a part of Assam or Bengal. “On one side, this was a matter of Bengali versus Assamese, and on the other, Hindu versus Muslim,” Hossain wrote.

Historian Anindita Dasgupta wrote in ‘Remembering Sylhet: A Forgotten Story of India’s 1947 Partition’, “… the Hindus of Sylhet demanded for a return to the more “advanced” Bengal, whereas the Muslims by and large preferred to remain in Assam where its leaders, along with the Assamese Muslims, found a more powerful political voice…”

But come 1947, this situation was reversed. Now the Hindus of Sylhet demanded to remain in Assam, and hence India, while the Muslims sought to join East Pakistan. This culminated in a controversial referendum on July 6 and 7, 1947 which sealed the fate of the region: 2,39,619 of the valid votes were for joining East Pakistan and 1,84,041 were for remaining in India.

When the official border was finally revealed in August, a part of Sylhet, comprising present-day Sribhumi (formerly Karimganj) district in the Barak Valley, remained in Indian Assam. In the initial years after Partition, a wave of Hindu Sylheti refugees settled in this region.

The story of Sylheti migration to parts of present-day Assam, Meghalaya and Tripura, however, is even older. Dasgupta wrote about “Sylheti Hindu bhodrolok” who were “economic migrants” across the region.

“Sylheti middle-class economic migrants to the Brahmaputra Valley and Cachar areas were a population in motion in colonial Assam, moving back and forth, many with simultaneous homes in both Sylhet and the Brahmaputra Valley districts and Cachar since the late nineteenth century,” she wrote in ‘Denial and resistance: Sylheti Partition ‘refugees’ in Assam’ (2001).

The Census of 1901 noted that “Sylhetis who are good clerks and are enterprising traders are found, in small numbers, in most of the districts of the province [Assam]”. There was thus a significant population of Sylhetis in what is now India well before East Pakistan, let alone Bangladesh, was even imagined.

Outrage in Barak Valley

The Hindu Bengalis of the Barak Valley are one of the strongest support bases for the BJP in Assam.

Malviya’s claim of the dialect being “a shorthand for the linguistic markers used to profile illegal immigrants from Bangladesh” has thus drawn strong reactions not only from the BJP’s political opponents in the Barak Valley but from within the party.

“Even today, at least three MPs and several state legislators across Assam and Tripura speak Sylheti natively… Over 7 million people in Northeast India — across Barak Valley, parts of Meghalaya and Tripura — speak Sylheti. They are proud Indian and Bengalis. To dismiss their language as something foreign, or ‘non-Bengali,’ is to rub salt in the wounds of a people already scarred by Partition,” prominent BJP leader and former Silchar MP Rajdeep Roy posted on X.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05