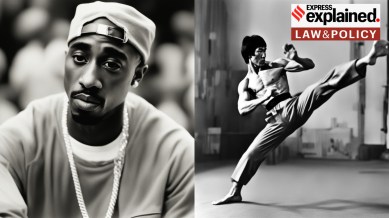

What California’s new law regulating use of deceased personalities’ likeness says

With generative AI now able to create convincing digital replicas of persons’ voice and physical likeness, California’s AB 1836 is a milestone regulatory measure which may pave the way for other jurisdictions to also consider similar protections.

In the face of artificial intelligence’s (AI’s) growing ability to replicate the voice and likeness of real people, the Californa State Senate on August 31 passed Assembly Bill (AB) 1836 to regulate the use of deceased personalities’ likeness without the consent of their families. The Bill now awaits the signature of California Governor Gavin Newsom, after which it will come into force.

Here is all you need to know.

SAG-AFTRA’s efforts to protect against AI

AB 1836 was co-sponsored by the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA), which referred to it as “a legislative priority for the union” in a statement on August 31.

Representing around 1.6 lakh US media professionals — including actors, broadcast journalists, dancers, DJs, singers, and stunt performers — SAG-AFTRA claims to be the world’s largest labour union representing performers and broadcasters. It went on a months-long strike last year over labour disputes with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP).

SAG-AFTRA’s contract with the trade association representing the interests of more than 300 movie and television production companies had expired on June 30, without no new agreement on the table. A major sticking point during contract negotiations was the use of AI to create digital replicas of the voice and likeness of public personalities, without proper compensation. This, SAG-AFTRA felt, infringed upon personalities’ rights over their own voice and likeness.

When the dispute was finally resolved on November 9, new agreements included wider protections for the creation, alteration and use of digital replicas based on performers, including background actors. SAG-AFTRA has hailed AB 1836 as another step towards “enhancing performer protections in a world of generative artificial intelligence”.

Defining “deceased personality”, who holds rights over their likeness

According to AB 1836, a “deceased personality means any natural person whose name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness has commercial value at the time of that person’s death, or because of that person’s death”. In US law, a person’s “likeness” typically refers to an image or representation of their face, body or other distinctive features such as their gestures and mannerisms.

The Bill states that a deceased personality will include all persons to have died since January 1, 1915 — 70 years before California first introduced legislation providing a post-humous “right to publicity” in 1985. This right prevents anyone from using a deceased person’s “name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness” without their families consent for a period of 70 years, from their death.

AB 1836 says that the rights to a deceased personality’s likeness are “property rights” which can be freely transferred through a contract. Upon the demise of a personality, these rights vest with their surviving spouse and/or children or grandchildren. If none exist, then the rights are vested with their parents or, in their absence and the absence of a contract transferring the rights to someone else, the rights are terminated.

Protections provided by AB 1836

At the outset, AB 1836 states that anyone who uses the “name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness” of a deceased personality without prior consent of her heirs “in any manner, on or in products, merchandise, or goods, or for purposes of advertising or selling” will be liable to pay damages.

These damages can be in the form of a $750 fine or based on the “actual damages” — calculated based on the economic loss caused to the heirs as well as any non-economic loss such as physical pain, emotional distress, etc. — whichever amount is higher. In addition, punitive damages can also be awarded to the heirs if the court so decides.

Further, anyone who produces or distributes a digital replica of a deceased personality’s voice or likeness, or uses such a replica in an audiovisual work or sound recording without obtaining prior consent for the heirs, will be liable to $10,000 fine or an award based on “actual damages”, whichever is higher.

The Bill defines a digital replica as a “computer-generated, highly realistic electronic representation that is readily identifiable as the voice or visual likeness of an individual that is embodied in a sound recording, image, audiovisual work, or transmission in which the actual individual either did not actually perform or appear, or the actual individual did perform or appear, but the fundamental character of the performance or appearance has been materially altered”.

Exceptions provided in AB 1836

The Bill exempts “a play, book, magazine, newspaper, musical composition, audiovisual work, radio or television program, single and original work of art, work of political or newsworthy value” so long as it is not directly connected with a “a product, article of merchandise, good, or service”.

The Bill also provides a list of ways digital replicas can be used without attracting a penalty. This includes using it in connection with:

- A news or sports broadcast;

- For the purposes of commentary, criticism, scholarship, satire or parody;

- A documentary, where the replica is used as a representation of the individual in a historical or biographical manner without creating a “false impression that the work is an authentic recording in which the individual participated”;

- A ‘fleeting or incidental use’; and

- An advertisement or commercial announcement for any of the above categories.