How Napoleon’s failed Egypt expedition gave birth to Egyptology

Napoleon sought to conquer Egypt to undermine British power. He failed. But the scholars he brought with him, have left an enduring legacy.

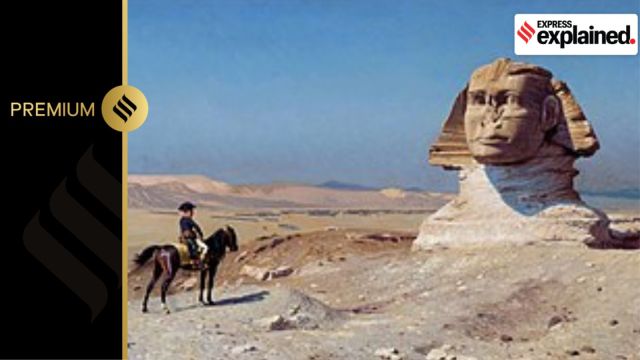

'Bonaparte before the Sphinx' painted by JL Gerome in 1886. (Wikimedia Commons)

'Bonaparte before the Sphinx' painted by JL Gerome in 1886. (Wikimedia Commons) A scene in Ridley Scott’s latest film depicts Napoleon directing his troops to fire cannons at the pyramids of Giza. Sensational as its may be, it is inaccurate — just like the famous apocryphal story of Napoleon’s troops blasting off the nose of Giza’s Great Sphinx (evidence suggests that the nose was chiselled off centuries before his time).

“From what we know, Napoleon held the Sphinx and the pyramids in high esteem,” Salima Ikram, a professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, told The New York Times. “He definitely did not take pot shots at them,” she said.

In fact, many scholars credit Napoleon for bringing Ancient Egypt to global consciousness, and literally giving birth to Egyptology as we know it. We take a look.

Driven by competition with the British

The French campaign in Egypt from 1798 to 1801 was driven by Napoleon’s colonial ambitions and a desire to stymie British influence.

“Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Ottoman Egypt in the summer of 1798 was intended to forestall the drift of that province into the British sphere of influence, and to interrupt British communications with India,” Juan Cole wrote in his book Napoleon’s Egypt: Invading the Middle East (2007). With the Ottoman Empire in swift decline, the French feared that former Ottoman possessions, with Egypt among the most coveted, would soon fall into the hands of the British or Russians.

In July, 1798, the French fleet landed in Alexandria and quickly captured it. Then Napoleon took Cairo, after the Battle of the Pyramids. Despite these initial successes, his operation soon started to falter. Not only did France not have enough men to establish sufficient garrisons, its navy was no match against the British.

Thus, by 1799, Napoleon himself fled the country. The French would hold on for another two years but effectively, any colonial designs Napoleon held were long laid to waste.

Powering global Egyptomania

Despite being a military failure, the legacy of Napoleon’s Egypt campaign can be felt till date. As Alexander Mikaberidze, an expert in Napoleonic history, told The NYT, the expedition can be credited with “the beginning of Egyptology, the beginning of this fascination with Egypt and the desire to explore Egyptian history and Egyptian culture.”

Along with his army of around 50,000, Napoleon had taken 160-odd scholars to Egypt — specialists in a wide range of fields, from botany and geology to history. The idea was to document and understand Egypt like never before, to capture the idea of Egypt, as much as its physical territories.

Take the example of Dominique-Vivant Denon, an artist and novelist. Denon sketched and collected data on numerous pharaonic monuments and published, in 1802, his monumental Travels in Lower and Upper Egypt.

“While there was no precedent for the number, size, and quality of his works, there was also no precedent in terms of the subject matter,” historian Miguel Angel Molinero wrote for The National Geographic in 2021. “The Egyptian monuments he drew — the Colossi of Memnon, the Temple of Hathor, and the Sphinx of Giza — had never been seen in such detail. Their beauty and distinction captivated France, and audiences were hungry for more,” he wrote.

In 1809 the first volumes of the 22-part The Description of Egypt were published. Containing nine books of text and 13 of plates, illustrations, and maps, they were published till 1828 — well after Napoleon’ death — and were seen as symbols of French national pride.

“For many modern scholars, the most enduring value of this work lies in the illustrations, for their fidelity and aesthetic dimension, accentuated by their enormous size. They mark the start of academic archaeology in the Nile Valley,” Molinero wrote. “The topographical plans are exceptional… About 20 of the buildings depicted have since disappeared and all that remains of their appearance are the figures and explanations in the Description,” he wrote.

Creating a market for Egypt’s antiquities

By sparking interest in Egypt, Napoleon’s expedition also created a thriving demand for Egyptian antiquities in Europe. French scholars wantonly seized artefacts from important Ancient Egyptian locations. This practice continues till date, often through clandestine and outrightly criminal channels.

Today, some of the greatest Egyptian antiquities, from Rosetta Stone which helped decipher ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, to the beautiful Nefertiti bust, all remain in museums far away from home, much to the chagrin of many within Egypt.

Thus, Egypt’s antiquities community has been working for years to repatriate as many artefacts as possible, although socio-political developments in the country do not make things easy. The Antiquities Coalition, a US-based nonprofit, estimated that following the 2011 revolution, about $ 3 billion worth of relics had been illegally smuggled out of Egypt.

(With inputs from The New York Times)

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05