At 8.52% in March, retail food inflation stood above the overall year-on-year consumer price increase of 4.85%, while ruling similarly higher for nine consecutive months since July 2023.

But there’s some hope for food inflation softening in the months ahead, providing leeway for the MPC to consider cutting the central bank’s benchmark interest rates. The drivers for this are primarily two.

1. The first is international prices

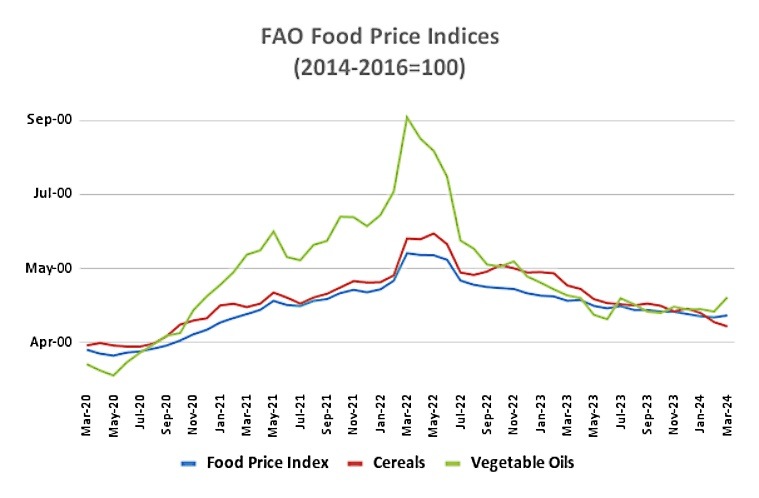

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization’s food price index averaged 118.3 points in March 2024. That’s a 7.7% drop from a year ago and 26.2% lower than the all-time high of 160.3 points touched in March 2022, just immediately after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The index – a weighted average of the world prices of a basket of food commodities over a base period value (taken at 100 for 2014-16) – had fallen for seven months in a row, from July 2023 to February 2024, before edging up in March.

The above rise has been mainly courtesy of the index for vegetable oils registering a jump from 120.9 points to 130.6 points. But even the latter is way below the peak of 251.8 points scaled in March 2022. The cereal price index, on the other hand, has continued its declining trajectory. At 110.8 points, the March index was 20% down from its year-ago level and 36.1% from its record of 173.5 points in May 2022 (chart 1).

FAO Food Price Indices (2014-2016=100).

FAO Food Price Indices (2014-2016=100).

Easing global food prices – a result of bumper harvests in key producing countries and supply lines being restored post the Covid and Ukraine War-induced disruptions – make imports more feasible.

Story continues below this ad

Take wheat, where the estimated stocks of about 7.6 million tonnes (mt) on April 1 were at a 16-year-low and precariously close to the minimum buffer norm of 7.46 mt for this date. As for the new crop, the harvesting of which has started, trade sources reckon its size to be lower by 3-4% in Rajasthan, 7-8% in Madhya Pradesh, 15-20% in Gujarat and 25% in Maharashtra.

The primary reason for that has been the delayed onset of winter this time: Above-normal temperatures in November-December are said to have caused premature initiation of flowering and cut short the crop’s vegetative growth phase in many parts of central India.

Fortunately, though, the wheat about to be harvested in Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar looks to be in good condition. The country’s overall production may, therefore, not be impacted as much. Equally fortunate, perhaps, is that the export price quotes of Russian and European wheat are now at $210-220 per tonne free-on-board (i.e. from the ports of origin), as against their March-May 2022 highs of $400-450 following the outbreak of the war.

Even after adding freight and other charges of $40-50, the landed cost of imported wheat would work out to around $260 per tonne or Rs 2,170/quintal – less than the government’s minimum support price of Rs 2,275/quintal for the domestically-grown crop.

Story continues below this ad

A decision on imports, which entails slashing the current customs duty of 40%, is more likely after elections. By then, Indian farmers would have also marketed their wheat, even as the new crop from Russia and Ukraine is ready for harvesting in July-August.

2. The second driver is a possible La Niña

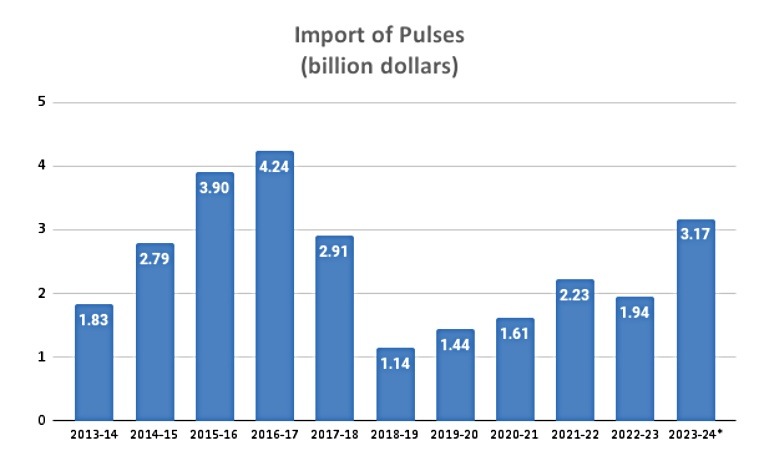

India’s pulses imports were valued at $3.17 billion during April-February 2023-24, over 80% up from the $1.76 billion for the corresponding 11 months of 2022-23. The fiscal year ended March 2024 may see total imports of almost $3.5 billion, the highest since the $3.9 billion and $4.2 billion in 2015-16 and 2016-17 respectively (chart 2).

*April-February 2023-24 (Source: Department of Commerce)

*April-February 2023-24 (Source: Department of Commerce)

The above surge in imports was attributable to El Niño – the abnormal warming of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean waters towards Ecuador and Peru, generally known to suppress rain in India.

2023 did see patchy southwest monsoon (June-September) rainfall, extending to the succeeding northeast (October-December) and winter (January-February) seasons as well.

Story continues below this ad

The brunt of dry weather was borne by Karnataka and Maharashtra, which are also major pulses-growing states. The Union Agriculture Ministry has estimated the country’s pulses output to have dipped to 23.4 mt in 2023-24, from 26.1 mt and 27.3 mt in the preceding two years.

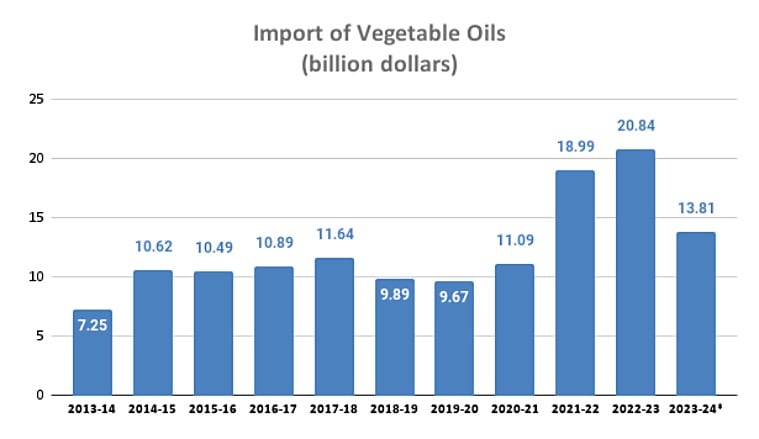

Imports – especially of red lentil (masoor), arhar (pigeon pea) and yellow/white peas (matar) – have kept a lid on prices. Retail inflation in pulses is, however, still too high for comfort (17.71% in March). This is unlike with vegetable oils (minus 11.72%), where the disinflation has come largely on the back of a global price crash and three years of record imports (chart 3).

*April-February 2023-24 (Source: Department of Commerce)

*April-February 2023-24 (Source: Department of Commerce)

The good news is that El Niño is weakening. The latest three-month-running Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) – which measures the average sea surface temperature deviation from the normal in the east-central equatorial Pacific region – for January-March 2024 was 1.5 degrees Celsius.

While that is thrice the El Niño threshold of 0.5 degrees, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has predicted an 83% probability of the ONI transitioning to a neutral range (less than 0.5 degrees) by April-June 2024.

Story continues below this ad

Further, there is a 62% chance of a La Niña (i.e. an ONI below -0.5 degrees Celsius or an abnormal cooling of the east-central equatorial Pacific water) developing during June-August 2024. That probability is even higher at 75% for July-September and 82% for August-October 2024.

Given the past association of La Niña with surplus rainfall in India – and these conditions expected to set in by the second half of the southwest monsoon season – it raises hopes of a bountiful agricultural year in 2024-25. To the extent that helps mitigate food inflation pressures, it would be manna from heaven for the government taking charge after the Lok Sabha election results in June 2024.

FAO Food Price Indices (2014-2016=100).

FAO Food Price Indices (2014-2016=100). *April-February 2023-24 (Source: Department of Commerce)

*April-February 2023-24 (Source: Department of Commerce) *April-February 2023-24 (Source: Department of Commerce)

*April-February 2023-24 (Source: Department of Commerce)