Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

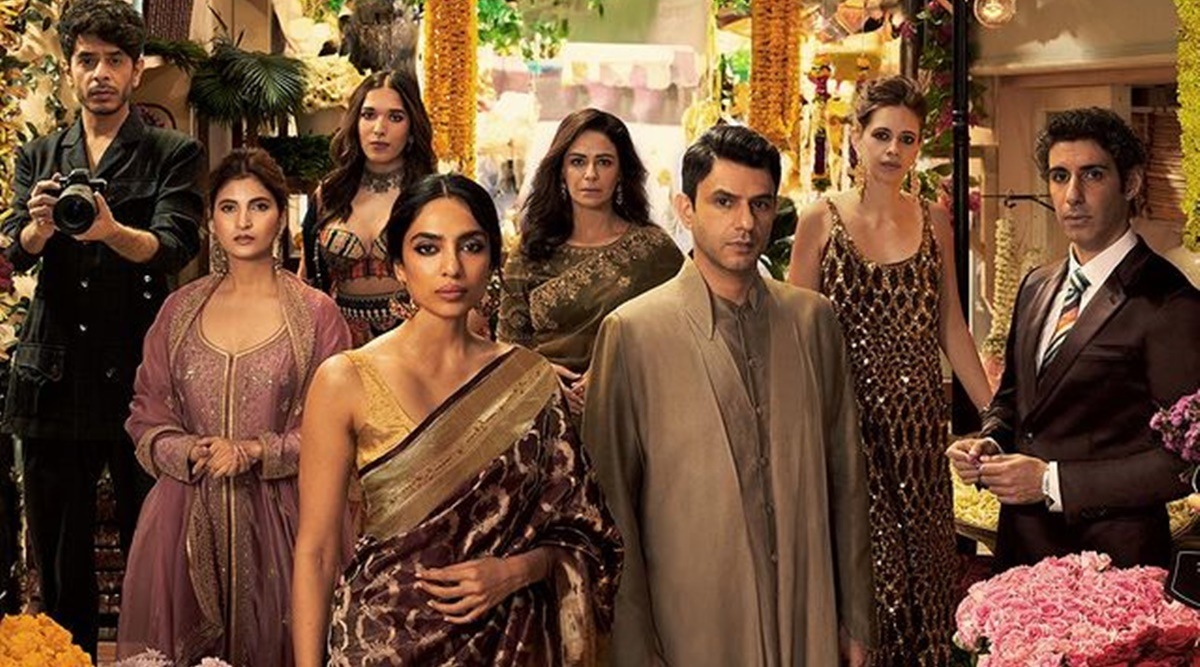

Made in Heaven season 2: Of lonely queers, scheming parents and perennial outsiders

Made In Heaven 2 puts things in mighty perspective. Love them or hate them, eventually a lot of it is indeed about your parents — and not in the way you thought it would be.

The second season of Made In Heaven makes a massive gamble.

The second season of Made In Heaven makes a massive gamble. One of the first lessons I got as a student of literature in the Unviersity of Delhi concerned politics of representation. As my professor poured over the 300-odd pages of a much-loved postcolonial novel, she told us in her usual trademark smile, “As literary critics in the making, you all must ask yourself one question when you look at a text. In the end, who dies? And why must they die? That is the standing answer to all your questions”. Despite being a mere snatch of a conversation from three summers ago, my professor’s words have stayed with me till date. And why would they not, for in many ways they fundamentally changed the way I was ever going to view any text that came my way.

The finale of Made In Heaven’s first season had made me simultaneously happy and bewilderingly sad. On one hand, Tara (Shobhita Dhulipala) and Adil’s (Jim Sarbh) marriage had clearly hit a rock bottom, a point of no return of sorts. This had also come on the heels of Tara’s big revelation; we as viewers knew now for sure that it was not just her desire to climb the social ladder that has propelled this show all along, but also the sheer extent to which she is willing to achieve the final end. But despite the ambushed office space, the undecided fate of the marriage, and the bittersweet separation of childhood lovers Nawab (Vikrant Massey) and Karan (Arjun Mathur) — the season finale was imbued with a certain sense of unprecedented joy. Because the image of Tara’s stolen jewellery and closing statement, “We’ll survive”, makes you realise that despite the hurdles all will eventually be good in the hood. These two indeed will survive and return for a new season.

Four years later, while the duo do return, they do so in a way that robs any hope that might have been instilled in our hearts at the end of the first season. If the first season made us think that a gay man living in New Delhi can fight the society at large and seek his own right to live with dignity, the second season makes it amply clear that the same gay man can continue struggling with issues of acceptance, commitment and plummet into the abject abyss of loneliness. A loneliness that is almost structural in its construction and while divorced frome alone-ness, almost an inalienable part of being queer in the urban space. If the first season made you think that perhaps, an outsider can indeed make her way to the inside by resorting to the most brutal means possible, the finale of season two tells you that in the larger scheme of things and in the moral framework of the show, an outsider will always be made unwelcome – every step of the way.

View this post on Instagram

And for a show where the leads are engaged in a profession whose mere baseline is to sell fairy-tales it is also funny how fairy tales are meted out to the two individual leads. The classic tale of two childhood lovers, separated by circumstance and reunited by destiny is turned on its head. The childhood lover, Nawab, returns only to tell a grieving Karan that his deceased mother was mean to him. A part of me was secretly hoping that the two unite by the end of the show, but the writers instead offer the two erstwhile lovers the show’s most profound scene. As Nawab gets up to get ready, Karan leans on his slept-in bed and embraces the sheets and in that moment Karan comes closest to being happy or comforted in the entire season. The “promise of happiness” that Sara Ahmed so passionately talks of, is never the share of an “unhappy queer” like Karan. His almost palpable and aching desire for Nawab finds closure only when he embraces the sheets that Nawab leaves in his wake. Only in absence, is there any sort of fulfilment of this desire? And this unhappiness and melancholy that remains his share throughout the film, is what exacerbates his queerness as a subject. Like it or not, the implications of such a representation notwithstanding, it is an interesting addition in the larger genealogy of queer characters from our Indian society.

On the other hand, Tara who begins her marriage as the ‘other woman’ and ends up making another other-woman woman out of her best friend, comes barely any close to reuniting with Adil. She gets the bare remnants of a deserted house, shuns a lover for his middle class aspirations and sits by the pool – a forever outsider. Meanwhile it is Faiza (Kalki Koechlin), who bears Adil’s future child, gets married in a ceremony – and considering that this is an Indian show, people must take note of the fact that she gets married in nothing less than a Sabya classic. The power balances are set right again. The queer is fated to the well of his loneliness, while the outsider continues to remain on the outside – no matter how hard she tries to get in.

For those whose hearts sink at this saddening state of affairs, worry not though. Not all is dark as far as affairs of the state go. There is ample reason to celebrate — for example the union of a lesbian couple (one of whom is a lawyer and looks dangerously like Menaka Guruswamy) and the affordance of a happy ending to a post-op trans lady Meher (whose journey of finding love in the city is laced with unprecedented and shocking layers of queer violence). In a surprisingly moving scene, Meher’s (Trinetra Gummaraju) mother video calls her daughter to check on her. She very casually says that Meher should have learnt cooking, not just to sustain herself as she lives alone, but also to increase her chances of finding a suitable groom. Such moments of parental kindness are treasures worth collecting in a show that is peppered with the most scheming of families. In retrospect, the more you watch Made In Heaven, the more you realise that marriages are indeed not just about two individuals coming together in love. These are individuals who are products of a larger socio-cultural upbringing, and in no way can one separate them from the same.

A recently released Hindi-language romantic comedy has very wisely put the role of the family in any marriage as the unit which dictates the essential “backseat driving”. Made In Heaven takes a dark and twisted look at this very idea. Karan’s mother breaks his arm when she first finds out about his affair with Nawab. She doesn’t meet her son in her final days and refuses to take chemotherapy on account of her son’s homosexuality. In the end, it is Nawab who comforts a grieving Karan and says that it is not necessary to like our parents to love them, and that sometimes it is alright to take our time in forgiving them. Tara’s mother is insistent that she fight for her fair share in the divorce settlement. She is disappointed when she starts dating a well-to-do chef (Ishwak Singh), with a business of his own. Tara, she argues, must only date heirs of giant business families with generations of wealth to boast of. Adil’s mother too is recalcitrant towards Faiza. After all she is a divorced, Muslim woman, who is on the surface atleast, responsible for breaking apart her son’s marriage. But the moment Faiza’s pregnancy is made known to her, all is forgiven. After all, blood is all that counts.

She is ruthless in her dealing with Tara as well. In a fantastically blocked and directed sequence, she agrees to loan money to Tara on the subtle condition that when the time comes she will manipulate her into giving into the divorce settlements. When things backfire yet again, she makes a last ruthless move. She leaves Tara a house – but it is only a mere cement and glass structure. She rips out the place’s guts from within. In a country that woke up to this millennium to the words of a blockbuster that said “It is all about loving your parents”, Made In Heaven puts things in mighty perspective. Love them or hate them, eventually a lot of it is indeed about your parents — and not in the way you thought it would be.

View this post on Instagram

The second season of Made In Heaven makes a massive gamble. There are no funny conversations about the weddings of rich people any more. We no longer have brides who cry over tulips and lilies or grooms who fall off horses. This time around, the pink palates pave way for something colder and much darker. This time it is no longer about the weddings alone, but also what weddings mean in our country. The highlight of the previous season with Shweta Tripathi walking out on her dowry-asking in-laws, is at a narrative level juxtaposed this season with Mrunal Thakur deciding to continue being married to a physically abusive fiance. Suddenly, despite the aspirational richness of lifestyle, the rich inner circles of the uber rich in this country are now laid bare before us. This is no longer a fun show to binge upon. It is a much darker meditation on what it truly means to just be in this country, in today’s day and age with or without a family of your own or your choosing.

- 0122 hours ago

- 0222 hours ago

- 035 hours ago

- 0422 hours ago

- 0522 hours ago