Click for more updates and latest Hollywood News along with Bollywood and Entertainment updates. Also get latest news and top headlines from India and around the World at The Indian Express.

Playing genius:

Seemingly twitching inside his own skin, Cumberbatch was Julian Assange, the WikiLeaker, in The Fifth Estate.

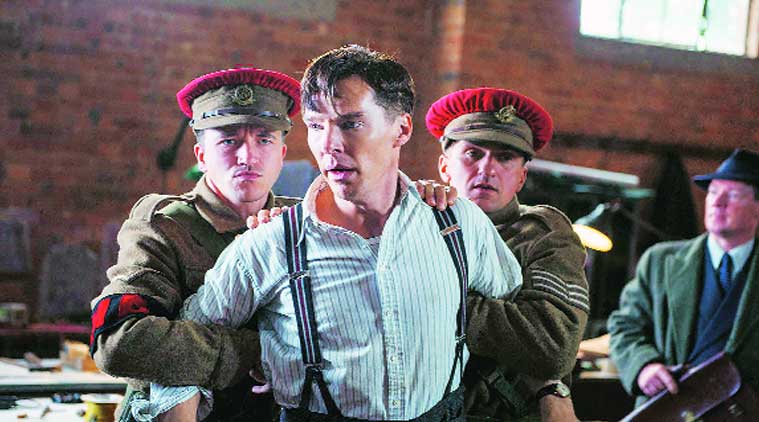

Cumberbatch stars in The Imitation Game as a brilliant British code breaker during World War II who is later persecuted because he’s gay. (Source: AP)

Cumberbatch stars in The Imitation Game as a brilliant British code breaker during World War II who is later persecuted because he’s gay. (Source: AP)

Benedict Cumberbatch has played Stephen Hawking, Vincent Van Gogh, Julian Assange, Star Trek’s Khan and won an Emmy for his portrayal of Sherlock Holmes. He now stars in The Imitation Game as another real-life genius, Alan Turing. Guess being brilliant comes naturally

With his wide forehead and high cheekbones, Benedict Cumberbatch has been compared, and not unreasonably, both to an otter and to Sid the Sloth from the animated movie Ice Age. He also has one of those rumbling, mellifluous British voices that are capable of revving up and whipping out dialogue, perfectly articulated, at breakneck speed. He can talk faster than most people think. Lately, all these gifts — the big brainpan, the quick tongue, the upper-class diction — have allowed him to make a reputation playing characters who are very bright but not quite normal.

Most famously, Cumberbatch is Sherlock Holmes in the BBC series Sherlock, a modern version of the legendary old sleuth, a bored, high-functioning sociopath, clueless about human emotion, who rattles off those famous Holmesian deductions at something like warp speed. He was also Khan, the genetically engineered alien in Star Trek Into Darkness, in which his sepulchral voice and rapid enunciation were themselves indication of unnatural villainy.

Seemingly twitching inside his own skin, Cumberbatch was Julian Assange, the WikiLeaker, in The Fifth Estate. And now in The Imitation Game, he is Alan Turing, the awkward, eccentric British genius who helped break the German Enigma code during World War II but was later persecuted by his own government, because he acknowledged his homosexuality, and forced to undergo chemical castration. His death, in 1954, may have been a suicide.

Cumberbatch’s Turing is not a fast talker — he stammers a little, as if his brain were whirring too fast — but a brilliant, sometimes acerbic one, and this portrayal is so poignant and affecting that it has earned him a Golden Globe best-actor nomination and put him on just about everyone’s Oscar shortlist.

“The thing about Benedict is that you can’t really put him in a box,” Morten Tyldum, the director of The Imitation Game, said recently. “He has so many layers, just like the character.”

While filming Shakespeare’s Richard III for the BBC, Cumberbatch took a couple of days off in November for the obligatory Imitation Game publicity tour — interviews, photo shoots, appearances on the Jon Stewart and Jimmy Fallon shows — and by the end he was visibly tired. At a downtown restaurant one afternoon, his voice occasionally slowed down as if his battery were running out. But Cumberbatch, in person witty and gracious in a way that most of his brainiacs are not, perked up when talking about Turing, a character he felt especially strongly about and whose treatment at the hands of the British government still made him grimace. “People are always asking me, what’s the most difficult job you’ve ever done,” he said. “I always say it’s the job I’m doing at the moment. But there are ones that really touch a nerve or connect with you, and with Turing there was such an urgency. It’s an extraordinary role, a great challenge for any actor, but at the same time you couldn’t ask for a nobler enterprise.”

About being typecast in brainy parts, Cumberbatch said, “Not such a bad fate if it’s true, but I don’t think it is.” He pointed out that he had been William Pitt in Amazing Grace and a plantation owner in 12 Years a Slave. And, he could have added, a gay secret agent in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, a World War I cavalry officer in War Horse and a creepy candy-bar manufacturer in Atonement.

A lot of people have compared Turing with Sherlock, Cumberbatch went on to say — both are brilliant, at deductive reasoning especially, and both are deficient in people skills — but he thinks the deeper connection is between Turing and Christopher Tietjens, the character he played in Parade’s End, the five-part 2012 BBC adaptation of a series of novels by Ford Madox Ford. Tietjens, loosely modelled on Ford himself, is a stuffy Yorkshire aristocrat clinging to Edwardian values on the eve of the Great War. He is said to be the cleverest man in London, but like Turing, he’s awkward with people.

“He’s a brilliant man, arrogant in the face of ineptitude and moral indiscretion,” Cumberbatch said. “He’s living in a very hypocritical era, and he’s a man out of step with his own time.”

Before hiring him, Steven Spielberg (who directed War Horse) had never seen Sherlock. Neither had Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave) nor Tyldum. John Wells, the director of August: Osage County, gave Cumberbatch the part of the needy, vulnerable Little Charles after Cumberbatch sent him a selfie audition on his cellphone.

“He was just extraordinary,” Wells said recently, “and I was a little embarrassed I didn’t know who he was.”

When director Susanna White hired Cumberbatch for Parade’s End, she hadn’t seen Sherlock either. She knew him mostly from his work on the BBC miniseries To the Ends of the Earth, in which he played a young British aristocrat travelling by ship to Australia.

White hired him not so much for his star quality as for his intelligence and quick-wittedness. The script, by Tom Stoppard, was dense and complicated, she explained, and Stoppard, who was on the set a lot, was fussy about having his lines spoken the way he wrote them. Because the character of Tietjens is not immediately likable, White also needed an actor who could make the audience fall in love with him. “It was a hell of a challenge,” she said. “But he has boundless energy. And he has this pure ability to inhabit a character.”

When she goes anywhere now with Cumberbatch, she said, they’re mobbed. “He’s not a matinee idol — he doesn’t have those looks — but people adore him. Everyone does: My teenage daughter. My mum, who is in her 90s. Suddenly he became huge overnight.”

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05