In 1974, Shree Rajneesh’s secretary Ma Yoga Laxmi travelled from Mumbai to Pune to look for a place to establish a permanent ashram. That day, she saw six different properties, including those in Koregaon Park and Mundhwa, with the help of Osho’s local followers. She almost finalised a property in Mundhwa and went back to Mumbai to obtain her Guru’s approval. However, a week later, she conveyed to the Pune contacts that the Koregaon Park property had been chosen.

Apparently, while taking a tour of the Koregaon Property – a bungalow on a 1.5-acre plot, she had stood under an almond tree and an unripe almond had fallen which she had taken to Mumbai and that had done the trick for Osho.

“She described all the properties in detail to Osho. She also showed the almond that she had taken from the property at Koregaon Park. Looking at the almond, Osho asked her to finalise this property, Ma Laxmi insisted that Osho himself should come and see the other properties before finalising it. He only said, ‘Purchase this very house in Koregaon Park’” B L Bagmar aka Satya Niranjan, a disciple of Osho, wrote in his memoir ‘Leave You My Dream: Osho Memoirs’.

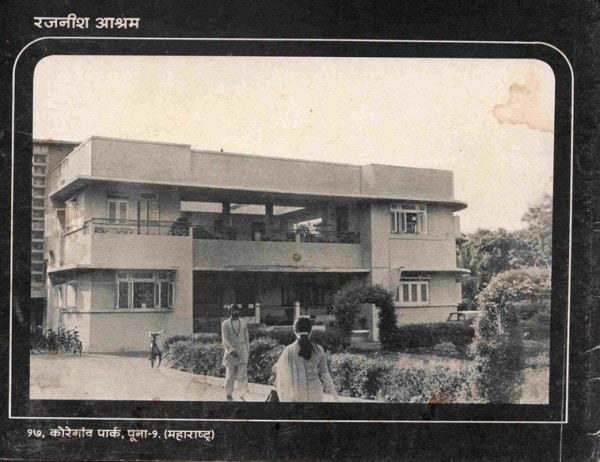

The property is ’33, Koregaon Park’. In a few months, it became Osho’s residence. Another property – Bungalow No.17 – was bought which became the office of the ashram and also gave it its postal address.

The establishment soon after Shree Rajneesh shifted to Pune. (Source: From Rajneesh Darshan magazine May – June 1974 issue),

The establishment soon after Shree Rajneesh shifted to Pune. (Source: From Rajneesh Darshan magazine May – June 1974 issue),

Today, a tall black wall and a canopy of trees hide the sprawling Osho Meditation Resort in Koregaon Park (KP) from the eyes of outsiders — but a seeker will see that the commune’s essential philosophy is available at the entrance itself. Near the metal detector and electronic gates is a thick cluster of bamboo, whose hollow core Osho symbolised to mean that people should empty themselves of the ego.

In 1974, Osho’s popularity was increasing in India and outside. He could fill stadiums with 20,000 to 30,000 people with his unconventional ideas on spirituality. Koregaon Park, on the other hand, was a leafy neighbourhood with a hundred-odd bungalows that belonged to erstwhile royal families and industrialists who occasionally stayed here.

“Pune used to be the summer capital of the Bombay Presidency. A lot of Maharajas had bungalows in the city and most of this was in Koregaon Park. They would come for the races, to interact with British authorities and participate in social events,” says entrepreneur Praful Talera. Osho would change the area and the city forever.

Story continues below this ad

Unlike other parts of Pune, where history goes back several hundred years, Koregaon Park began to be developed only around a century ago. Before that, it was “an unkempt area…a jungle and a hideout for asocial elements” with a few mansions on the outskirts of the wasteland, according to the book, Pune: Queen of the Deccan. In the 1920s-40s, the land was cleared and the plots sold. “Many of the Indian princes built their mansions here,” say the writers Jaymala Diddee and Samita Gupta in the book.

Inside the Osho resort

The 1971 law to abolish privy purses impacted the finances of the erstwhile royal families and many of them began to sell off their property. It was on such bungalows that the Rajneesh Ashram was first set up. The first two acquisitions, namely No.33 and No.17 became Lao Tzu House and Krishna House, respectively.

Plot number 18 is where the Buddha Grove stands today, a marbled open space where all of Osho’s talks were given under a giant mosquito net.

“People were coming in hordes and Osho was in a hurry. He wanted trees and water bodies in the commune, which meant mosquitoes. When the municipality didn’t give permission to build a permanent structure, a large mosquito net was made to protect him and his disciples,” says Ma Amrit Sadhana, who is a part of the management team of the meditation resort.

Story continues below this ad

At first, only Indians came to the resort, then a flood of Western disciples arrived. The requirement of the space changed and more halls were needed for meditation. In 1987-88, the commune acquired a few more bungalows. The space kept growing. “Osho left his body in 1990, after that the commune spanned 28 acre, which includes 16 acre of plots and 12 acre of Osho Teerth, a public park taken on lease from the municipality,” says Sadhana. The old structures were renovated to make way for halls and spaces where Osho meditations can be practised. “Osho’s talks provoked a lot of people because he wanted to destroy all that was old and raise new humanity. We can see that in the architecture of the commune, which were inspired by his insights into designing,” she adds.

Rajneesh Ashram in late 1970s. A still from German filmmaker Wolfgang Dobrowolny’s Ashram in Poona.

Rajneesh Ashram in late 1970s. A still from German filmmaker Wolfgang Dobrowolny’s Ashram in Poona.

All buildings, for instance, are of black granite, a colour considered inauspicious in almost all traditions. Several of Osho’s early disciples left because they thought that the colour was unlucky. “But, black is also for mystery, for grounding and absorbing negativity,” says Sadhana. The Meditation Resort has gleaming black living quarters and meditation spaces, among others, with names such as Lao Tzu House, Krishna House and Radha Hall. One of the most important structures of the meditation resort is the pyramid — a shape that preserves energy — which is in black. It is called the Osho Auditorium. The glass of most of the windows is blue, “for calming the senses”.

In another unorthodox move, the Meditation Resort has an undulating surface made up of inclines and hillocks. “It would have been easy to flatten the land but Osho wanted us to live in synchronicity with nature, where the ground is rarely smooth,” says Sadhana. The commune has a balance of greenery — big trees, shrubs, ground cover — and waterbodies. Apart from winding streams, there are waterfalls on giant boulders brought especially from Saswad. “The whole plan is to calm the nerves and bring peace and silence,” says Sadhana.

The Meditation Resort inherited several old jamun and jackfruit trees from the previous bungalow owners but the majority have been planted by the sanyasis according to Osho’s wishes to fill 50 per cent of the land with greenery. At one time, he had suggested that each tree be given a name. “The trees do not have a utilitarian end as we do not take fruit or flowers from them,” says Sadhana. At the house where Osho used to stay, and where his Rolls Royce welcomes devotees to meditation, the garden is thick with green and silent. Parrots and other birds flit among the branches. The sound of people is muffled.

Story continues below this ad

Near the open-air dining hall— covered during the monsoon — is an odd, amoeba-shaped swimming pool with a story of its own. When bungalows number 15 and 16 were acquired by the Meditation Resort in 1991, there were trees all around and patches of bare land. “Osho always said, ‘Don’t cut the trees’ so we made the pool with the spaces in between without disturbing the beautiful trees,” says Sadhana. The tennis courts at the Meditation Resort are more conventional.

Osho Teerth is one of the meditation resort’s key gifts to Pune. Old Punekars, such as historian Pandurang Balkawde, say that it used to be a wasteland where garbage was dumped near a canal and pigs roamed. The meditation resort has taken it on a 99-year lease from the municipality and, after an arduous process of two years, developed it into an ecological park with a profusion of trees, lanes, waterbodies and seating. “It is a great contribution of the Osho commune to the city,” says Balkawde. If the road that runs past the resort looks better maintained than most in the city, it is because the commune harnessed German technology to construct it.

The Meeting of Cultures

At the beginning, it was not easy to come to Pune from other cities and even tougher to reach Koregaon Park since rickshaw service was practically non-existent. But, Osho’s population of disciples grew. Sanysis congregated from all corners of the US, Europe and other countries, seeking emancipation. By some estimates, Pune had almost as many foreigners as Delhi at the time. Dressed in maroon robes, they easily outnumbered the locals in Koregaon Park. The neighbourhood began to acquire a different accent from the rest of Pune which was, itself, transforming into an academic hub. “While Osho ji was alive, it seemed as if we were in a foreign country when we stepped into Koregaon Park. There would be thousands of foreigners all over the area,” says Balkawde.

Business minds were the first to sense the changing winds of Koregaon Park. Locals along the river began to set up shacks to rent out to sanyasis who, in the initial days, used to pay in dollars. Rickshaws began to ply and charge exorbitantly. “A lot of the sanyasis were very evolved, and a whole economy came up around them,” says Talera. Hotel Sunderban Resort and Spa, for instance, was set up to cater to the devotees of Osho.

Story continues below this ad

German Bakery, Pune’s famous eatery, was born in the 1980s to serve the sanyasis. “My father, Dnyaneshwar Kharose, started his career selling cigarettes outside the resort, where he got to know a lot of foreigners and realised that they were not getting a bite to eat as per their taste. We did not have a cuisine that they would like,” says Snehal Kharose, the proprietor of German Bakery, who remembers the long marble-topped tables occupied by sanyasis who were playing chess, checkers or stemming the guitar between meditation sessions. “A lot of hotels, small dhabas and tapris came up. Since the disciples belonged to all kinds of economic backgrounds, they were catered to according to their own lifestyle,” says Balkawde. A music scene flourished because sanyasis, who were into celebration and dance, were attracted to restaurants and cafes playing a certain kind of live music. These restaurants also maintained a high level of hygiene for their international clientele.

The bohemian attitudes of the sanyasis found many detractors in Pune, culminating in an assassination attempt on Osho on March 22, 1980. A little more than a year later, Osho left to set up a new — and controversial — commune in Oregon in the US. “In India, we grow up with philosophy, mythology and spiritualism in a way that a monotheistic society of the West would not understand. The evolved Western mind understood Osho but the common person could not. Many of us feel that Osho’s Koregaon to Oregon move was a bad one,” says Talera. Osho returned to the Pune centre in January 1987 and stayed here until his passing away in 1990.

The enduring legacy

His disciples kept coming to Pune, despite difficulties and contributing to its development. Vida Heydari, an Iranian, was in Canada, when she first read a book of Osho. She didn’t know who he was nor had she ever practised yoga or meditation. Heydari travelled from Toronto, with two long transits in between, and arrived in Mumbai. “It was my first time in India and I didn’t know anyone. I thought it was not safe to take a taxi, so I waited for a mini bus. I had to wait several hours through the night, and that mini bus was giving everybody a ride until we arrived at Koregaon Park after six hours. I was the only woman in that mini bus which was frightening since the entire trip happened through the night. Add to that, it was monsoon and pouring heavily,” she says.

The meditation had an impact on her, so she kept coming back for more. Travelling to Pune also became easy over the years, thanks to the developed airport and better connectivity through the Mumbai-Pune highway. “I realised that there was a lot that I wanted to know and work on myself. I made a lot of trips. It got to the point that every holiday and free time I had was spent either coming here or trying to figure out a room in my schedule so that I could come here as much as I wanted. A lot of international crowds began to stay half the year in Pune, sometimes longer,” she says.

Story continues below this ad

Heydari is now married and lives a walking distance from the meditation resort so that she can be close to her spiritual master. She also runs the VHC, an art gallery-cum-resto-bar that showcases cutting-edge works, encourages local talent and represented Pune at the recent India Art Fair and India Design Fair in Delhi. VHC also holds weekly live music events and, a few weeks ago, some sanyasis attending it mentioned that the space resembled the resort because of all the trees. Somebody even mentioned that Heydari had black decor. “I have heard this from at least six people. It’s nice to hear because none of this was intentional. I hadn’t even noticed how much Osho had influenced my subconscious,” says Heydari.

The establishment soon after Shree Rajneesh shifted to Pune. (Source: From Rajneesh Darshan magazine May – June 1974 issue),

The establishment soon after Shree Rajneesh shifted to Pune. (Source: From Rajneesh Darshan magazine May – June 1974 issue), Rajneesh Ashram in late 1970s. A still from German filmmaker Wolfgang Dobrowolny’s Ashram in Poona.

Rajneesh Ashram in late 1970s. A still from German filmmaker Wolfgang Dobrowolny’s Ashram in Poona.