Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

Laugh Riots

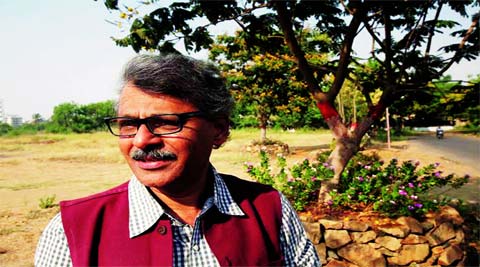

Shafaat Khan, a key figure of ‘70s Marathi Experimental Theatre movement, on his fascination with satire and the second feature film he has penned, Dekh Tamasha Dekh.

Shafaat Khan is known for his flair with black comedy.

Shafaat Khan is known for his flair with black comedy.

An event from the 1992 Bombay riots had left a strange impression on playwright Shafaat Khan. The day the riots broke out, Khan was at Shivaji Park when a man came running towards him. The man had survived a bombing that sent the roof of a double-decker bus he was in, flying. Reeling from the absurdity of the event, he was laughing out loud as he described it to Khan and others. “When you are helpless, and there is nothing you can do about it, the only thing left to do is laugh,” says Khan, as he cites German dramatist Bertold Brecht’s famous quote: “Nothing is funnier than human tragedy”.

Khan evokes similar emotions in his works for satires such as Crows of Bombay (1976) and Shobhayatra (2004), his Marathi plays; and the recently-released Dekh Tamasha Dekh (DTD), the second Hindi feature film he has written, which is being appreciated for its scathing socio-political commentary.

The need to show an issue, Hindu-Muslim conflict, in a different perspective made Feroz Abbas Khan, the director of DTD, seek Khan’s writing services. Their film strings together several bizarre real-life events. Take for instance, where after a man, born Hindu but living with a Muslim widow for years, dies from an electric shock, villagers from both the communities claim the body, which results in riots. In another, a cop in Kolkata faces suspension when a police dog, under his charge, becomes pregnant. Then there’s one where an “innocent” thief is burnt alive when Hindu mobs attack a Muslim household during the Godhra riots. These, when assembled in a small-town setting, become a microcosm for India.

“These may seem surreal to the West, but our societies are full of such absurdities, nothing is fabricated and all that we’ve shown has really happened,” says 61-year-old Khan, sitting in his office, the Department of Theatre at the University of Mumbai, Kalina. A visiting faculty there for over a decade, he has recently been appointed as the head of the department.

A product of the Marathi experimental theatre movement of the late ’70s, Khan is known in theatre circles for his biting dark humour that “makes you laugh at things one shouldn’t laugh at: taboos such as death, war or riots”. “It’s a dangerous, tricky area, as people may get offended,” says Feroz, who describes his writing as something that can “stretch the most ridiculous to a point where it touches the heart”. He remembers Khan from the ’70s as “someone with an absurdist streak”, whose plays were being adapted in inter-collegiate drama competitions even while he was a student at Khalsa College. His seminal work Shobhayatra (2004) was adapted into many languages subsequently and even made into a Hindi feature film by the same name, which was also Khan’s feature film debut as a screenwriter. The play sets itself amid the mock rehearsal for an Independence Day parade, featuring nationalist heroes such as Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose.

The characters, who populate the world in Khan’s writing, such as those in DTD set in a coastal Konkani small town, are more symbols than characters “meaningfully designed to make the audience examine reality by trying to understand the bizarreness”. Khan jokingly says that his fascination with black humour may have to do with his Konkani-Muslim roots, where people from his village Banda, Sawantwadi district have a way of “talking in an oblique rather than a straightforward way”.

Khan’s works emerge out of the socio-political climate, as in the ’70s, when the Marathi theatre movement was looking to “address concerns of a new kind, of a new generation”. During that phase, Khan along with important theatre practitioners such as Satyadev Dubey, Makarand Sathe, Amol Palekar and Shriram Lagoo, broke the traditional norms of theatre to create an exciting, radical hybrid form.

Today, he says, the biggest crisis in Marathi theatre is not the lack of ideas but shortage of actors. “After spending three to four months in theatre, the actors shift to films and television. You can’t blame them, there is no money in theatre,” says Khan. Undeterred, he is working on his latest play, Dry Day, another satire that’s set in a city bar, where artists engage in conversations with the bar owner, an art enthusiast.

sankhayan.ghosh@expressindia.com