Teacher and theatre critic Keval Arora retires from Kirori Mal College; students, past and present, mark end of an era

Arora’s abiding legacy are his former students who are spread across theatre, cinema, television and other professions, such as Mohammad Zeeshan Ayyub Khan, star of Article 15 (2019) and Raees (2017); and Geetika Vidya Ohlyan, who starred in the critically acclaimed Thappad (2020).

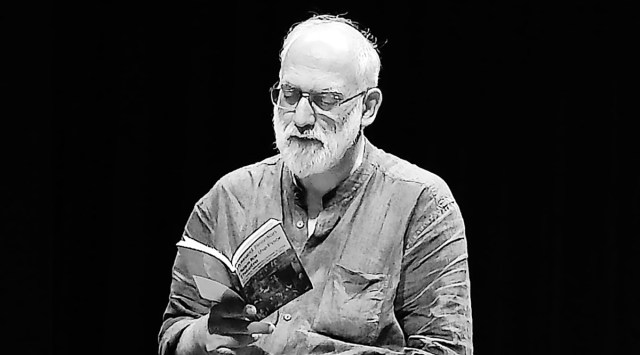

Arora retired from KMC after four decades. (Photo by Imran Khan)

Arora retired from KMC after four decades. (Photo by Imran Khan)On Saturday, as Keval Arora walked out after his final lecture at Delhi University’s Kirori Mal College (KMC), he was greeted by around 150 former students of all age groups who had gathered to mark the moment. Their applause lasted more than 10 minutes. Later, there was a farewell event to mark Arora’s four decades at KMC as well as 65 years of the college theatre group, The Players, whose staff advisor and moving force he had been.

“What started as an extra-curricular activity right after I entered KMC soon took over my entire being. The Players drew me into the world of plays and live performances. Keval Arora mentored us closely, asking questions that profoundly transformed me, such as ‘what can art and theatre do’? He’d spent countless hours discussing literature, philosophy, and performance to help us develop our own understanding. This experience made me want to be who I am today — a theatre director and an artist,” says Amitesh Grover, a performance maker and faculty member of the National School of Drama in Delhi.

Arora’s abiding legacy are his former students who are spread across theatre, cinema, television and other professions, such as Mohammad Zeeshan Ayyub Khan, who starred in Article 15 (2019) and Raees (2017); and Geetika Vidya Ohlyan, who starred in the critically acclaimed Thappad (2020). Arora joined The Players in his second year at KMC and, after becoming faculty in 1980, assumed the staff advisor-ship of the theatre society from its founder Frank Thakurdas, who was a legend in theatre and trained Arora. Arora has made occasional appearances in cinema, notably as the father to Rajkummar Rao’s Omar Sheikh in Hansal Mehta’s Omertà, and a boys’ school principal in John Abraham-produced Banana.

Abhipsito Das, a recent English Honours graduate at KMC, recalls that he was designing a poster for a play as part of The Players and told Arora that he wanted the distance between two graphics to be four millimetres. Arora disagreed and asked him to keep it at seven. Das kept the distance between four and seven millimetres and sent Arora the first draft. “He was angry and I was scared. I apologised, he cooled down and we got back to working together — but he had that kind of eye, to notice even such minute details with his work,” says Das.

Arora has always been a popular teacher, especially for the dollops of wit and seriousness he tossed at his students in the classroom. Fuzaila Khan, a third-year English student of KMC, says that he did not want to be addressed as ‘sir’ and never missed a chance to disrupt a serious academic discussion with a joke. “When I went in for my ECA auditions and he was the judge, I was intimidated when I saw him,” says Harshini Misra, a recent graduate of KMC and ex-member of The Players. “But he cracked the lamest joke and I relaxed.” Rudrashish Chakraborty, Arora’s colleague of 21 years in KMC, says that disruption was a part of Arora’s teaching method, “He provoked students to think out of their comfort zone, think critically, and never compromised on his principles,” he says.

Chakraborty says that Arora belonged to the generation of teachers who had studied in the 1970s and transformed the discipline of English studies in DU into the vibrant cultural and political space it is today. “It is the end of an era,” he adds.

Arora insisted on democratising every space he entered, with alumni of the society saying he told them not to take institutional structures for granted. “It was with him that we understood what democracy really means,” says Nakul Singh Sawhney, documentary filmmaker, founder of ChalChitra Abhiyaan and ex-member of the society. “He was heavily invested in our work but encouraged us to make our own mistakes. He was the staff advisor but considered himself no more important than any of us,” he says.

Mallika Taneja, a Delhi-based performer, calls Arora a patient teacher who represented “the finest definition of a teacher”. “His marathon classes on Waiting for Godot are famous. It used to go on from morning to evening and was attended even by students from other colleges,” she says.

Arora’s reputation for reticence and quiet hard work impressed his colleague in the KMC Chemistry Department and staff advisor for KMC’s music society, Shalini Baxi. She had been selected by Delhi University Vice-Chancellor in 2017 for a task of taking a team plucked from across the university to participate in the prestigious Edinburgh Festival Fringe. She approached Arora to be the mentor of the programme. “I knew that if he refused, I’d refuse. Thankfully, he agreed and it was a very successful production that he spearheaded,” she says.

“If you have heard him talk, it’s mesmerising because he would combine academic integrity with lovely language — it is beautiful to listen to him,” says Arora’s colleague Amrapali Basumatary. “That is why we are crying our eyes out, because we are trying to figure out how to carry on the department without him, knowing the brilliant pool of students and work ethic he has left behind.”

(With inputs by Dipanita Nath)