When it feels (swipe) right: Finding love in Delhi, one match at a time

From migrants finding their ticket to freedom to longtime Delhi residents looking to get out of the traditional mores, dating apps gave many in the Capital a reason to hope this year – risks and challenges notwithstanding

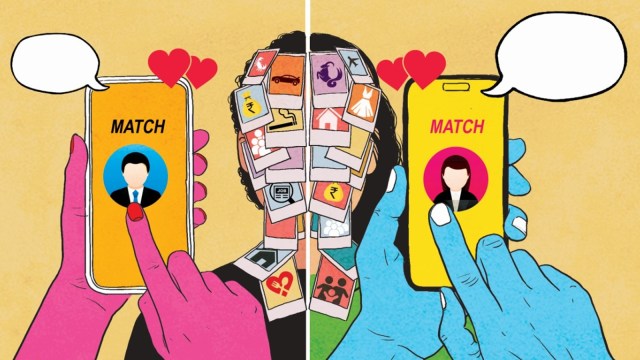

Online dating seems to have become a norm more than an exception for young adults looking for companionship in a busy, demanding modern world. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey)

Online dating seems to have become a norm more than an exception for young adults looking for companionship in a busy, demanding modern world. (Illustration: Suvajit Dey)As the sun sets on the lake at the 14-Century Hauz Khas Fort in Delhi, a 23-year-old woman settles down with her cappuccino at a tony café a short distance away. Her hair is tied up in a sleek bun, her make-up minimal – soft pink blush on her cheeks – but it is her eyes that do the talking. Oscillating between her smartphone and the cafe entrance, they finally stop at the latter as a strapping young man walks in. This is a 25-year-old ed tech employee, and more importantly, the woman’s “match”.

The duo connected on a dating app last week; this is their first in-person meeting. The woman is excited but also nervous. “The first dates always feel like this. It is like I’m battling with myself, wishing that the person is just as appealing, if not more, in reality as they seemed online,” she shares as she fiddles with her gold earrings. “My parents think I am out with college friends. They wouldn’t understand this… modern way of meeting people,” says the Rajouri Garden resident.

Until a decade ago, the couple who met online would have been an anomaly. But with technology rapidly taking over every aspect of life, online dating seems to have become a norm more than an exception for young adults looking for companionship in a busy, demanding modern world. And Delhi, being a melting pot with people from all walks of life and parts of the country making it their home, seems to be playing a perfect backdrop for fledgling virtual-to-real love stories to play out.

While the 23-year-old met her online match in person, a 22-year-old Delhi University (DU) student is still weighing his options. His thumb hovering over his smartphone screen, the multiple dating apps at his disposal have opened up a world of possibility and hope outside of his conservative family in his hometown, Kanpur, in Uttar Pradesh.

“I am the first among my cousins to try out this dating method,” he declares as he swipes right on a potential match.

The proliferation of smartphones and dating apps has revolutionised how young Delhiites approach relationships. During the pandemic in 2020, Tinder became a virtual lifeline for many, providing much-needed human interaction. An official statement from the app noted that “60% of members came to Tinder because they felt lonely and wanted to connect with people. Gen Z specifically sought out Tinder to meet new people and get out of their echo chambers.”

Like the student, a 20-year-old woman is finding a way out of her small-town life through the few dating apps that dot her phone screen. “My parents are already talking about arranged marriage, but I want to explore. Dating apps give me that freedom,” says the woman, an undergraduate DU student who hails from Haryana’s Fatehabad.

She finds the option to make the first move on Bumble “empowering”. Recounting a date from a few months ago, she says, “We went out for a drink and it felt good, it didn’t pan out into a relationship, though.”

To be sure, meeting a potential partner through the online medium is not entirely new for Indians what with a multitude of matrimonial websites, riding the “dotcom boom”, proliferating the internet over the last few decades.

For a 30-year-old banker who lives with his parents in Dwarka Sector-23, though, these websites are yet to catch up with what modern partner-seekers want. “It is a frustrating process as the people I met on these (websites) are very conservative. What usually matters is one’s salary package, caste, and whether the horoscopes match or not. I don’t believe in astrology and, being a part of these platforms, I felt I was going against my beliefs,” says the man, who eventually transitioned to Hinge, where he found a partner “more in line with his values”. He has been dating her for two months now.

The banker’s success story does little to assuage the skepticism of a 27-year-old psychologist about dating apps. “It is like shopping for a partner…,” she says. “The endless choices can be overwhelming. You keep second-guessing every connection because you know there are always more profiles to look at.”

Having found a partner at her workplace, the woman, who hails from Madhya Pradesh’s Bhopal, says she feels relieved about being “out of the online dating cycle”. “It is exhausting to keep up with conversations. Sometimes, people ghost you for no reason, or you feel pressured to perform, to be interesting at all times…Trust is also a big issue,” she tells The Indian Express.

An interesting aspect of Delhi’s dating revolution is how age plays a role in the apps people choose. While Tinder and Bumble dominate among 18-25-year-olds, slightly older users between the ages of 25-35 lean toward apps like Hinge and Aisle. Hinge, which brands itself as “designed to be deleted,” appeals to young professionals who are increasingly tired of the casual dating scene.

Other variables like career goals, cultural expectations, and the desire for deeper connections further shape the experiences of older daters. The psychologist says, “… Career-focussed people often look for partners with similar ambitions. That’s why apps like Aisle are appealing — it’s not just about looks, but lifestyle compatibility… The desire for deeper connections grows with age… By the time you’re nearing 30, you’re looking for more than just a fling.”

A 29-year-old entrepreneur, who works in the field of fashion, agrees. A resident of Southwest Delhi, she recounts her experience of transitioning from Tinder to Hinge: “When I was younger, Tinder was fun — meet someone, grab a drink, maybe see where it goes. But now I’m at a stage in my life where I’m looking for something more serious. Hinge feels like the right place for that. People seem more grounded, more open to having deeper conversations.”

She shares that she once spent weeks texting a guy on Bumble “… but despite me initiating a meeting repeatedly, he never showed any interest. One day, he finally agreed to meet… but that day, I was left in a coffee shop… he never showed up… That was a wake-up call for me…”

A 22-year-old student at Miranda House also says it is hard to find someone truly compatible. “Even on dating apps, people make judgments based on where you live, which car you drive, or even your last name,” she laments.

In a world where the line between online and offline is a razor-thin one, it is also hard to compartmentalise a connection in one straight, neat category. Sharing one such experience, the Miranda House student says, “I met this guy at a college fest and we got talking. That felt more organic than dating apps because there were no expectations right away. But we eventually added each other on Instagram, and it, sort of, blended into online dating!”

For many, compatibility means also being on the same page in terms of religion. This is where religion-specific apps, such as Muzmatch and Salaam, which target Muslims, come into play. “I was looking for a serious relationship and one within my community…,” says a 41-year-old professional. Although, the skewed gender ratio, here in favour of women, made him back off. “You end up matching with very few people as compared to women,” he shares.

For Delhi’s LGBTQ+ community, dating apps are a double-edged sword. While they provide them the anonymity to explore their sexuality without the prying eyes of society, they also expose them to criminals looking to take advantage of their vulnerability.

“Someone asked me to send them money. Another time, my photos were used to create fake profiles,” says a 22-year-old from Jasola Vihar.

A 28-year-old shares similar experiences on Grindr. “He asked me for minimal amounts, like Rs 1,000-Rs,1,500, citing a family emergency. This is when I unmatched with him,” he shares about a date. In another instance, he was stunned to find pictures of his body on someone else’s profile.

These two experiences are not isolated cases. Over the last few years, cases of people using fake profiles on dating apps to extort money or inviting people on dates only to present them with an inflated bill in connivance with café staffers have made headlines.

The 2022 case of Shraddha Walkar, who met her partner, later accused of murdering her, through Bumble is still fresh in many minds.

However, the hope of finding love through the virtual medium, where most youngsters spend a huge chunk of their waking hours these days, seems to override the risks.

As a Master’s student at South Asian University sums it up: “Dating in Delhi is like the city itself — chaotic, contradictory, sometimes frustrating, but always exciting. We are all just trying to find our way, one date at a time.”