Why PAU is reassessing PR-126 variety nine years after introduction: ‘timing holds the key’

Last year, millers refused to store this paddy, claiming its OTR did not meet the FCI specifications, set at a minimum of 67%, and a lower OTR means they will have to pay from their pockets

Punjab Agricultural University (PAU), releases survey report on different sowing timings for the PR-126 rice variety.

(File Photo)

Punjab Agricultural University (PAU), releases survey report on different sowing timings for the PR-126 rice variety.

(File Photo)Punjab Agricultural University (PAU) recently released a survey report on different sowing timings for the PR-126 rice variety from June to August to inform farmers how these varying sowing periods affect the yield, moisture level and the milling out-turn ratio (OTR) of this variety.

After “conducting all required tests and trials”, PAU introduced this variety in Punjab in 2016.

Considered one of the PAU’s best paddy varieties so far in terms of short duration, good yield, resistance to pests and consistently desirable OTR, among other qualities, a large area under rice cultivation in the state is producing this variety. However, ahead of the paddy transplanting season in Punjab in June, PAU undertook a fresh survey on the performance of this variety — why?

That too, after nine years, given a large area in Punjab, is already producing PR-126 variety. The Indian Express explains:

Why PR-126 matters?

Paddy is an extremely water-intensive crop, and despite a severe groundwater crisis in Punjab, the area under paddy cultivation has been increasing every passing year.

Last year, the state recorded the highest 32.44 lakh hectares under paddy cultivation, producing different varieties, ranging from short to medium to long-duration types.

In such a scenario, shifting to shorter-duration paddy varieties is one of the best options to conserve water. That’s how the PR-126 variety comes in.

After its introduction in 2016, this variety quickly gained popularity among farmers due to its shorter growth period, high yield (over 30 quintals per acre), minimal pesticide requirements and excellent OTR.

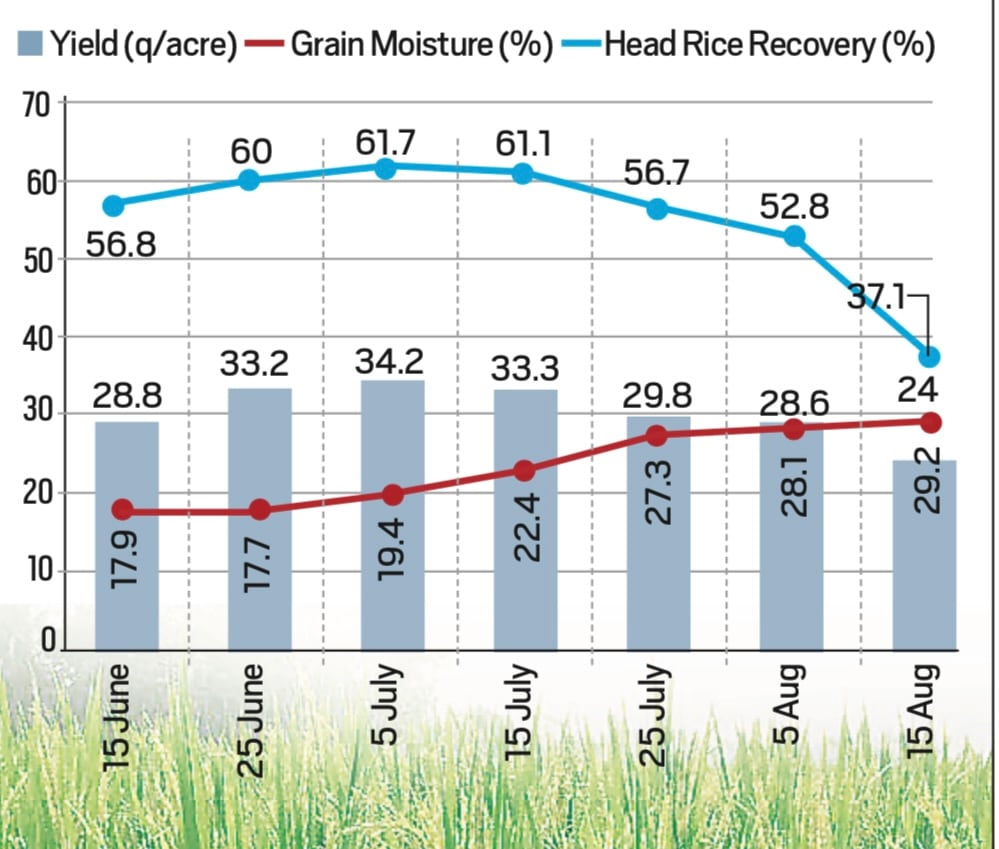

Key findings from the survey reveal that PR-126 performs best when transplanted between June 25 and July 15, using 25–30-day-old seedlings, as very early and very late transplantation led to yield reduction.

Key findings from the survey reveal that PR-126 performs best when transplanted between June 25 and July 15, using 25–30-day-old seedlings, as very early and very late transplantation led to yield reduction.

PR-126 matures in just 93 days after a 25 to 30 days of transplantation, using less water, producing less straw (making residue management easier), and providing a longer gap between rice harvesting and wheat sowing.

This is also resistant to major pests and diseases, reducing the input cost significantly.

In 2023, PR-126 was cultivated over approximately 8.59 lakh hectares, almost 33 per cent of the total area under non-Basmati paddy cultivation in Punjab. This increased to 43 per cent this year.

Additionally, PAU sold around 7,500 quintals of PR-126 seeds this year, in addition to seeds saved by farmers and produced by several paddy seed breeders in the state.

Why did PAU conduct a survey despite its popularity?

Last year, rice millers raised a large hue and cry about the procurement of PR-126 and several high-yield (up to 36 to 38 quintals per acre) hybrid paddy varieties by the government.

They refused to store itin their mills, claiming the OTR of this variety did not meet the specifications of the Food Corporation of India (FCI) set at a minimum of 67 per cent, and alower OTR means they will have to pay from their pockets to the FCI.

Procurement is carried out by the government or private agencies based on FCI’s specifications.

The major parameters for purchase at the Minimum Support Price (MSP) include — grain moisture content not exceeding 17 per cent, and mixture of lower-class grains not more than 6 per cent, damaged, discoloured, sprouted, or weevilled grains should not be above 5 per cent and immature, shrunken or shrivelled grains should not more than 3 per cent.

PAU strongly argued that it releases any new variety after rigorous testing for three years on all possible parameters, including yield, OTR, and pest resistance.

However, millers remained adamant and refused to store PR-126 and several other hybrid paddy varieties, citing low OTR.

Later, the government intervened and millers stored it.

Thus, PAU initiated this survey to dispel this notion and demonstrate the variety’s relevance and profitability for farmers and the environment.

What’s this survey about?

Recently, issues related to inconsistent yields, high grain moisture, and milling quality surfaced, especially when PR-126 is transplanted too early or too late, or when aged seedlings are used.

According to the survey, out of the 43% area covered by PR-126 during Kharif 2024, a sizeable portion was transplanted very late (from the second fortnight of July to August 10).

This area was typically transplanted after summer maize—a practice PAU does not advocate.

The very late transplanting resulted in issues with yield, grain moisture content, and milling quality.

Key findings from the survey reveal that PR-126 performs best when transplanted between June 25 and July 15, using 25–30-day-old seedlings, as very early and very late transplantation led to yield reduction.

Aged seedlings (35-45 days) can reduce yield by 7.8 per cent to 18.9 per cent.

After July 15, yield, grain quality and milling recovery begin to decline.

As a result, PAU is advising farmers to transplant PR-126 between late June and mid-July, use 25–30-day-old seedlings, avoid very late transplanting (after July 15), and ensure proper drying and handling for better grain quality to maximise productivity.

Is case of banned hybrid varieties in Punjab similar to PR-126?

Like PR-126, the notified hybrid paddy varieties — also cultivated in Punjab for several years — have been blamed for low OTR last year only.

Experts from the seed industry suggest that harvest moisture content, rather than the seed variety, may be a key factor affecting milling outcomes.

“Optimal milling requires grain to be harvested with 22-23 per cent moisture, dried to 16-17 per cent for procurement, and milled at 13-14 per cent,” they explain.

Delayed procurement, often due to bad weather conditions from late sowing and logistical bottlenecks, can lead to excessive field drying, causing grain breakage and lowering OTR regardless of the variety.