Can an outsider tell the story of India? Revisiting the legacy of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

As I See It: At the heart of the debate lies concerns about whether an outsider can truly understand places, people, and psyches that are not their own. And if they can, whether that understanding should be accepted as authentic?

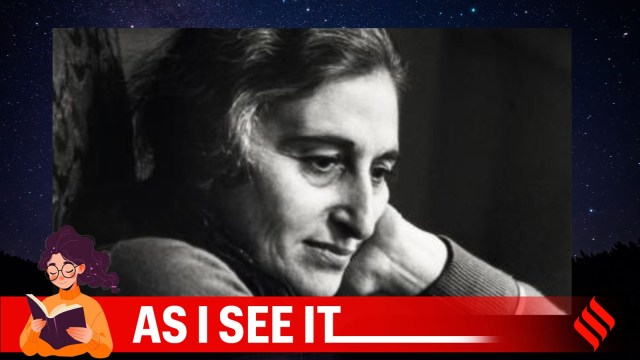

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala is a German-born, British-raised, Indian-residing author and screenwriter. (The Booker Prize)

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala is a German-born, British-raised, Indian-residing author and screenwriter. (The Booker Prize)At a creative writing seminar, our class found itself grappling with the polarising question: who has the right to write about whom? Can a non-Indian writer authentically capture Indian experiences? The discussion, while lively, was inconclusive, as is often the case with questions of representation and narrative authority. No one left with a definitive answer, and perhaps that was the point.

At the heart of the debate lies concerns about whether an outsider can truly understand places, people, and psyches that are not their own. And if they can, whether that understanding should be accepted as authentic?

Few writers test the boundaries of that debate more than Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, the German-born, British-raised, Indian-residing author and screenwriter. The only person ever to win both a Booker Prize (Heat and Dust, 1975) and an Academy Award (A Room with a View, 1986), Jhabvala is paradoxically revered in film circles, and overlooked in literary ones. She is rarely included in the Indian canon, despite living in Delhi for over two decades.

What does it mean to be an ‘Indian author’?

Jhabvala herself, in a 1974 interview, dismissed the notion of being called an “Indian writer,” aligning instead with the tradition of European authors who have written about India from the outside looking in. It was a statement which in theory, should have ended the debate. But it did not not because what Jhabvala produced, particularly in her fiction, was a literary cinema of Indian life that defies easy classification. Her short story collection Like Birds, Like Fishes reveals an author whose understanding of Indian domesticity did not come from cultural inheritance but from prolonged proximity and observation.

Ruth married Cyrus Jhabvala, an Indian Zoroastrian and moved to Delhi, India, the place she called home for the next 24 years. (ruthprawerjhabvala.com)

Ruth married Cyrus Jhabvala, an Indian Zoroastrian and moved to Delhi, India, the place she called home for the next 24 years. (ruthprawerjhabvala.com)

Her prose, tinged with irony and vulnerability, often illuminates Indian masculinity in ways rarely explored. In The Interview, for instance, a male narrator wrestles with the power dynamics of the household: “All the time I was eating, I could feel my sister-in-law looking at me and smiling. It made me uncomfortable… It was as if she were saying, ‘You see, you will always have to be dependent on us.’”

There is something delicate in how Jhabvala exposes the emotional dependencies of men, especially in our culture. Her work invites comparison with Anita Desai, another chronicler of interiority.

Jhabvala and Naipaul

However, Jhabvala’s most telling counterpart may be found not in India but in Trinidad. VS Naipaul in his seminal novel A House for Mr Biswas charts the existential unease of a man who, though ethnically Indian, is geographically and spiritually unmoored. Like Jhabvala, Naipaul approaches Indian-ness not as a given, but as a question.

In one early passage, Naipaul sums up Mr Biswas’s insecurities: “It gave Mr. Biswas some satisfaction that, in the circumstances, Shama did not run straight off to her mother to beg for help… Now she tried to comfort Mr Biswas, and devised plans on her own.”

Both authors, though writing from different vantage points, share a preoccupation with the vulnerability of Indian men. In Jhabvala, that vulnerability is social and often domestic. In Naipaul, it is existential, rooted in dislocations of post-colonial identity. But in both, it is rendered with unusual empathy and complexity.

So, who gets to tell these stories? The question, while important, may be less useful than we think. Rather than gatekeeping perspective, perhaps the more pressing task is to interrogate what is done with it. How deeply it looks, how honestly it listens, and how thoughtfully it depicts the world it seeks to portray.

Jhabvala, like Naipaul, may not “belong” to the tradition she depicts. But she lived in its shadows and side streets long enough to sketch them with care. Her work may never satisfy those in search of cultural purity or representational precision. But it endures because it does what good literature must: it sees.

(As I See It is a space for bookish reflection, part personal essay and part love letter to the written word.)

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05