Udit Misra is Senior Associate Editor. Follow him on Twitter @ieuditmisra ... Read More

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

- Tags:

- Express Premium

- eye

- Sunday Eye

Latest Comment

Post Comment

Read Comments

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal at the inaugurating Mahila Mohalla Clinic at Kali Mata Mandir near Bangla Sahib Road on Wednesday. (Express photo by Prem Nath Pandey)

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal at the inaugurating Mahila Mohalla Clinic at Kali Mata Mandir near Bangla Sahib Road on Wednesday. (Express photo by Prem Nath Pandey)With Delhi going to the polls on Wednesday, this is a timely and interesting book not just for the voters in the Capital but also for those curious outside it. The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which came into existence in 2012, first formed the government in Delhi in 2013 and after a brief initial stint, won two back-to-back landslide victories in Delhi in 2015 and 2020. The mandates it received would have made any political party anywhere in the world proud but to achieve them as a newly minted party shows how much the Delhi voters trusted the AAP and its promise to bring about a systemic change (vyavastha parivartan).

Its supporters believe that only the Arvind Kejriwal-led AAP can provide a robust governance model for India. The AAP also attracts equal detractors who believe the party represents all that is cynical and fake about Indian polity. It is hardly surprising then that Delhi has been voting in a singularly polarised manner since 2014: It gives landslide victories to the AAP in state Assembly polls while giving sweeping victories to the BJP, the main Opposition party in the state, in the national (Lok Sabha) polls.

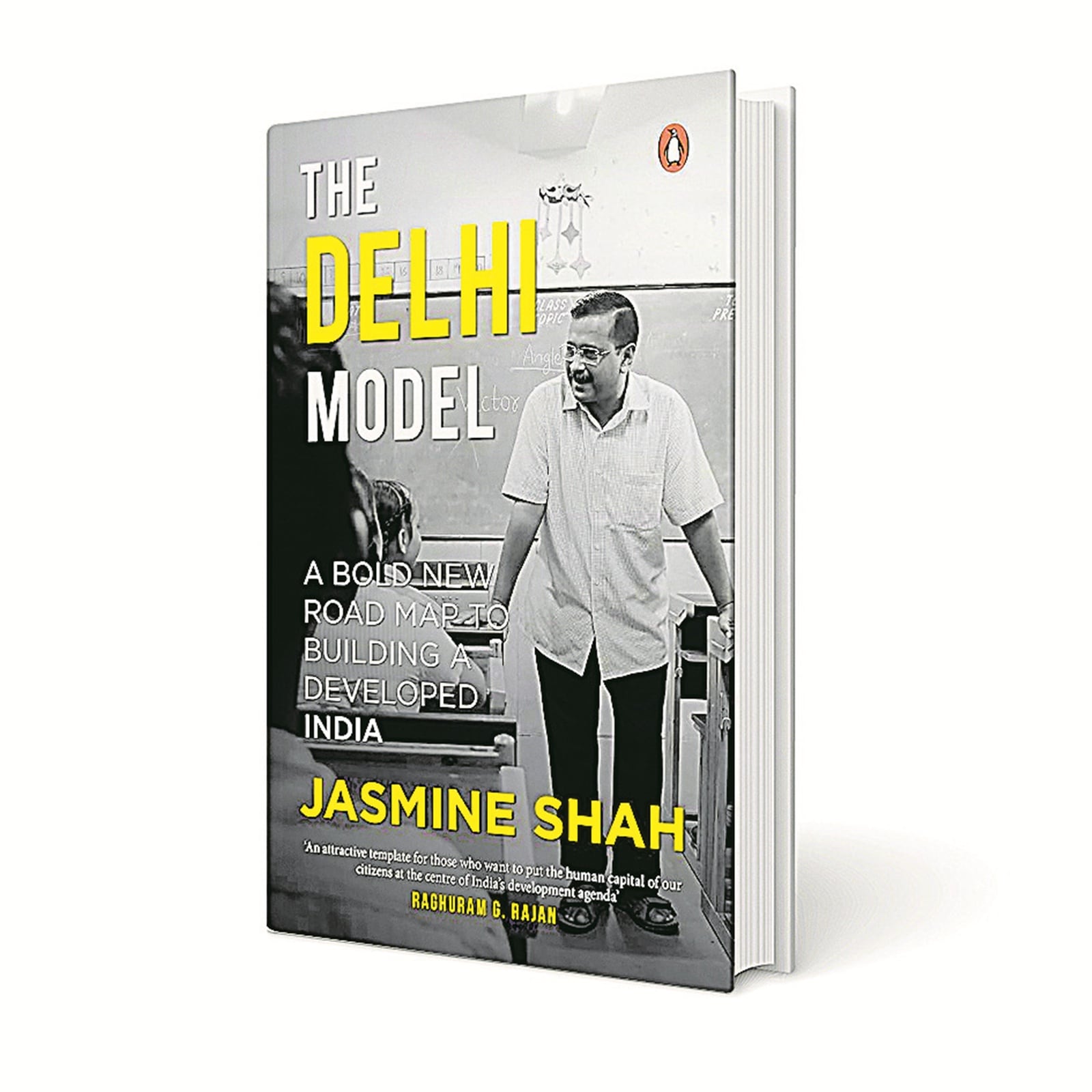

The Delhi Model

The Delhi ModelThe book details what the author calls The Delhi Model of governance, referring to the AAP’s rule and initiatives in India’s national capital since 2013. Don’t expect a very even-handed account, however, since the author is an AAP member. That doesn’t necessarily mean the book is not based on facts — it has a long list of references — although AAP detractors might have quibbles with the author’s assertions about the improvements in Delhi’s governance over the past decade.

Author Jasmine Shah, an alumnus of IIT Madras and Columbia University, was deputy director of MIT’s Poverty Action Lab in South Asia, before he joined the AAP in 2016. He explains that “at its core”, the Delhi Model of the AAP rests on three principles. “First and foremost, prioritise investments in building human capabilities and improving the quality of life of the aam aadmi — the lower and middle classes… Second, declare a war on corruption, for corruption eats into the government’s limited budgets and directly compromises the delivery of government schemes and programmes meant to transform the lives of the aam aadmi. Third, make a firm commitment to fiscal prudence.”

Over eight chapters, Shah details how the AAP’s initiatives have improved governance across education, health, air pollution, public transport, electricity and water provisioning. The sum of the AAP’s essential argument is summarised in the first chapter that explains how the party pushed on each of the three aforementioned principles. Equally important is the last chapter — ‘Democracy under Attack’ — that details AAP’s frequent run-ins with the BJP. The author not only details how the Centre unleashed its investigative agencies to hold back the AAP, but also asks a broader question: Who gets to govern Delhi?

So, has the AAP come through on all three pillars of the so-called Delhi model? It is a fact that no other state spends anywhere close to what the AAP spends (as a percentage of their budget) on health and education. Similarly, there is evidence that the aam aadmi’s access to electricity and water has improved. Delhi residents suffered the lowest inflation in the past decade and this is again borne by data. However, Delhi’s air pollution, despite the state government’s efforts, continues to be a national shame and serious health concern for the state’s population.

On corruption, the book blames the BJP for holding back the AAP by taking away the control over the Anti-Corruption Branch (and placing it under the Central government) and, first stone-walling the Jan Lokpal Bill, and later rendering the institution toothless. Still, the author details several initiatives — doorstep delivery of public services and elimination of touts — that reduced everyday corruption. Another example is the reduction of tax terrorism via unnecessary raids.

On fiscal prudence, the data is in AAP’s favour. Notwithstanding the BJP’s claim that the AAP is only about winning elections by giving freebies, the state has the lowest debt-to-state GDP ratio of all Indian states. At the heart of this book as well as the choice before the Delhi voters is a dilemma: Should the government follow trickle-down economics (where tax cuts for the rich and physical infra get precedence) or a trickle up one (where boosting human capital, especially among the poor and middle class, is prioritised)?