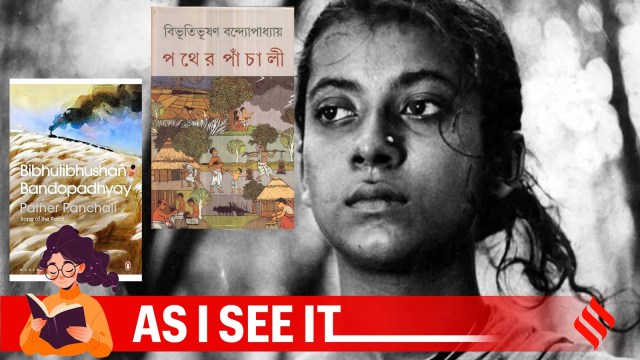

Durga does not ask to be liked. She does not fit in, not in her home, not in her village, and not in the version of girlhood her world demands she perform. Ordinary but unforgettable, she pushed boundaries, talked back, and wandered too far too often much to everyone’s dismay. But beneath her stubbornness lay hunger – for beauty, for escape, for something more than what her narrow world could offer. In Pather Panchali, she is the fire burning quietly in the shadows in stolen moments of freedom: a walk in the rain, a secret laugh, a glance at something just out of reach.

I first met Durga in the pages of Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay’s 1929 novel in a dusty classroom. We were both around the same age and shared the same angst. She was angry, misunderstood, and ostracised for wanting the ordinary. For me, and for many readers, Durga reads less like a character and more like a girl you once knew – or once were.

She disobeys, steals, lies, laughs, dreams. Her small, rural world doesn’t know what to do with her, so it punishes her for existing on her own terms. In the few chapters she occupies, Durga lingers far beyond the page. Her mother scolds and strikes her, neighbours accuse her of theft, and the poverty of her home leaves little room for understanding the emotional life of a girl on the edge of adolescence. But Bandopadhyay never flattened her into a victim.

Story continues below this ad

Durga’s longings are small, intimate, and piercingly relatable – a fruit, a train, a forbidden hut. These modest dreams, some left unmet, represent something larger: the condition of countless girls whose wants are neither voiced nor honoured. In one line, Bandopadhyay writes of her as “that one poor girl from the village and her many unfulfilled desires.” The line contains the quiet heartbreak of generations – of girls asked to be less, to want less, to vanish quietly.

The train whistles past

Her strongest desire was to see a train. She never gets to. That unfulfilled dream becomes a metaphor for everything else she’s denied – movement, wonder, freedom.

Which brings us to Apu, her younger brother and the book’s protagonist, and their bond. Their relationship exists in glances and shared silences in a world which has no time for childhood. While the adults are worn down by poverty and exhaustion, Apu and Durga carve out a world where love exists – wordless, mischievous, protective.

Apu follows her like a shadow, learning and absorbing. She shows him not the world as it is, but as it could be. She steals fruit and dares him to follow. She dreams of trains and lets him in on that dream. Together, they claim the only kind of freedom available to them – in play, in secret paths, in shared imagination.

Story continues below this ad

This is what makes Durga’s sudden and untimely death so shattering. She fades away without ceremony. But her absence haunts the novel’s emotional landscape.

In what I consider the most piercing moment in the book, Apu, after her death, discovers a small gold box she had stolen from her neighbour – the very theft she had always denied. She had begged and wept, insisting she hadn’t taken it. She never even confessed to Apu. Now, holding the truth, Apu makes a decision. He doesn’t tell anyone. He throws the box deep into the forest, where he believes no one will find it. It could have helped his family, perhaps brought them some money. But that thought doesn’t even cross his mind. In that act, Apu protects Durga – her memory, her dignity – from a world that never understood her in life. A final stand for his sister he loved the most.

Later, as he boards the train Durga never got to see, he weeps. “Didi, I didn’t forget you or leave you behind. They are taking me away…” he tells her silently in his heart.

He carries her with him and her dying words for life: “Apu, when I get better will you show me the train one day?”

Story continues below this ad

As he takes the train out of his childhood, his village – where every corner contains remnants of his sister – he cries and he remembers her.

Indian girls have Durga

Female teenage angst and unfulfilled desire, especially in literature, were rarely given space during that era. While male characters were often allowed rebellion and interiority (Catcher in the Rye, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man), girls were usually boxed into roles of restraint, obedience, or romantic yearning. Durga breaks that mold. She is impulsive, angry, and instinctively resists domestic expectations.

In Manik Bandopadhyay’s short story Samudrer Swad (Taste of the Sea), a young woman weeps constantly and inconsolably without a word to anyone.

In Manik Bandopadhyay’s short story Samudrer Swad (Taste of the Sea), a young woman weeps constantly and inconsolably without a word to anyone.

This theme echoes in rare but powerful instances across Indian fiction. In Manik Bandopadhyay’s short story Samudrer Swad (Taste of the Sea), a young woman weeps constantly and inconsolably without a word to anyone. It was over her dead father’s unfulfilled promise of taking her to see the ocean. Nothing in her life could console her and she couldn’t talk about it with anyone. Like Durga, she is not allowed to be angry at anyone. She is quietly heartbroken that the world denied her something so small, yet so important. These girls do not ask for the universe. They ask for moments. And they are denied even that.

Durga exists at the intersection of many things – poverty, girlhood, rebellion, adolescence – but she is not reduced by them. What makes her extraordinary, even nearly a century after she was written, is that Bandopadhyay does not punish her for wanting. He lets her be.

Story continues below this ad

For many readers – especially young girls – Durga may well be one of the first characters they see themselves in. Not because she’s heroic, but because she yearns. Not because she triumphs, but because she’s never truly heard. Her tragedy isn’t just that she dies young – it’s that she dies before anyone truly sees her.

Pather Panchali is remembered as Apu’s story but its soul lies in Durga. She may not be the protagonist in structure, but emotionally, she carries the heart of the novel. She teaches us that even the smallest dreams can carry unbearable weight in a society where girls and their wants are considered radical.

(As I See It is a space for bookish reflection, part personal essay and part love letter to the written word.)

In Manik Bandopadhyay’s short story Samudrer Swad (Taste of the Sea), a young woman weeps constantly and inconsolably without a word to anyone.

In Manik Bandopadhyay’s short story Samudrer Swad (Taste of the Sea), a young woman weeps constantly and inconsolably without a word to anyone.