Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

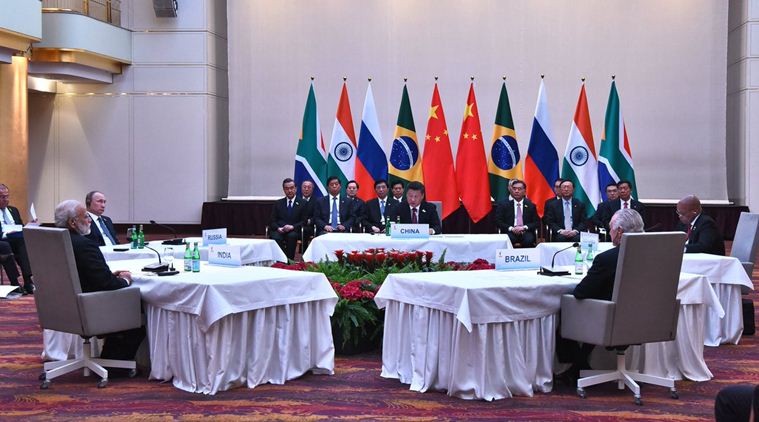

BRICS Summit: Why India can’t leave the big stage entirely to host China

India has to ensure that the BRICS meeting does not end up as a meeting of former bearers of hope.

BRICS Summit: The five member countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – were once seen as emerging economic superpowers.

BRICS Summit: The five member countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – were once seen as emerging economic superpowers.

The BRICS summit in Xiamen this month is a welcome occasion for the host China to demonstrate once again its significance and grandeur – both to the domestic constituents as well as to the outside world – ahead of the all important 19th Congress of the Communist Party.

Delicate issues have been excluded from the agenda of the gathering, as Beijing can ill-afford to have any nuisance ahead of the crucial reorganisation of its political leadership. Instead, the members will probably focus on consensual topics such as free trade, climate change and cybersecurity. Last but not the least, the challenges of a digitised economy, the central theme of India’s BRICS presidency last year, are still on the agenda.

However, the big stage and the displayed unity cannot conceal the fact that China has long moved away from the basic idea of the BRICS grouping, and, among other things, is pursuing its own plans with its “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) and intends to further expand its pre-eminence.

From hope-bearers to troubled kids

To make matters worse, the original hopes about BRICS have all but evaporated; the times of their unbridled economic growth are long gone.

The five member countries – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – were once seen as emerging economic superpowers. It seemed only a matter of time before they would overtake their Western peers, which have struggled to reform their economies. But the euphoria about BRICS has now vanished.

The boom in China’s economy, which accounts for two-thirds of the entire bloc’s GDP, has run out of steam, with double-digit growth rates now a thing of the past. In 2016, China’s GDP growth rate was a far modest 6.7 percent. For 2018, the Chinese economy is forecast to expand by 6 percent.

Chinese President Xi Jinping. (PTI File Photo)

Chinese President Xi Jinping. (PTI File Photo)

With this “controlled slowdown” Beijing wants to reconfigure its economy – to transform it into one driven by domestic demand and services rather than exports and the manufacture of cheap products.

This has so far proven to be a risky maneuver, however. In addition to the well-known excess capacities in the heavy industry, the highly speculative real estate boom and the widespread high corporate indebtedness, China’s foreign exchange reserves are shrinking at a rapid pace.

File photo

File photo

Russia appears to be in a more dismal state: The decline in oil prices and the sanctions imposed by the West due to Moscow’s annexation of Crimea have hurt the economy, dragged down the value of the Rouble and boosted inflationary pressures. The situation has already prompted President Vladimir Putin to start selling and privatising state property in an attempt to funnel money into the government’s empty coffers.

The situation in Brazil is even more dramatic. Politically and economically, the Latin American bearer of hope finds itself in a state of crisis. The low oil price has also led to an economic downturn, with Brazilians consuming less and unemployment rising. Regardless of its current political crisis, the Brazilian government has faced financial difficulties for a while now, as the whole world could witness during the last World Cup football tournament in 2014.

The African member of BRICS, South Africa, too, is struggling economically. Growth has slowed down considerably over the past five years, trade imbalance has been stubbornly high and government debt has reached a critical level. Compounding the poor economic conditions are political uncertainties and bad governance that are frightening foreign investors, whom the country needs so badly.

A source of hope

In this context, India remains a source of hope within the BRICS club. The nation’s economy is clearly on a better trajectory than that of other members, although growth appears to be losing steam in recent quarters.

In the quarter to June, GDP grew 5.7 percent, its slowest pace since the January-March quarter 2014, government data showed. Still, strong growth in the services sector and capital investment point to a quick potential rebound in economic activity in Asia’s third-biggest economy.

Even the often double-digit inflation rate is now under control. India is becoming more and more interesting for foreign investors, especially as the previously closed sectors are increasingly being opened up for foreign direct investment.

At the same time, the growth-stymying bureaucratic hurdles are expected to be reduced further along with the harmonisation of numerous regulations among the nation’s 29 states.

All of these raise great hopes. However, India is still faced with major challenges – at least two-thirds of the population remains excluded from the newly generated prosperity. And compared to the 1970s, the 800 million Indians living in the rural parts of the country now have much less food available. This is an untenable condition, especially for a member of the BRICS group.

Not a one-way street

In the BRICS club, India plays quite rightly an important role. But if this group really wants to be more than just a acronym, it needs a strong common theme that brings together every member. This would also be a good way to reduce the recent tensions between India and China.

India should therefore give a greater impulse to the bloc and not leave the big stage entirely to China, which wants to expand its clout with its BRI project and other initiatives. Wherever China’s claim to power conflicts with the interests of other BRICS partners and where the BRI becomes a one-way street for expanding Chinese influence, India should also be alarmed.

Written by Alexander Freund

Alexander Freund is Head of Asia Programs at Deutsche Welle. This article comes in special collaboration with Deutsche Welle, Germany’s public international broadcaster

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05