Stay updated with the latest - Click here to follow us on Instagram

25 years of reform: The Shrinking of Bombay

India’s financial capital was a global city long before 1991. Liberalisation changed it in other insidious ways.

By history and evolution, and as much by the Mumbaikar’s sheer will, this was always a global city.

By history and evolution, and as much by the Mumbaikar’s sheer will, this was always a global city.

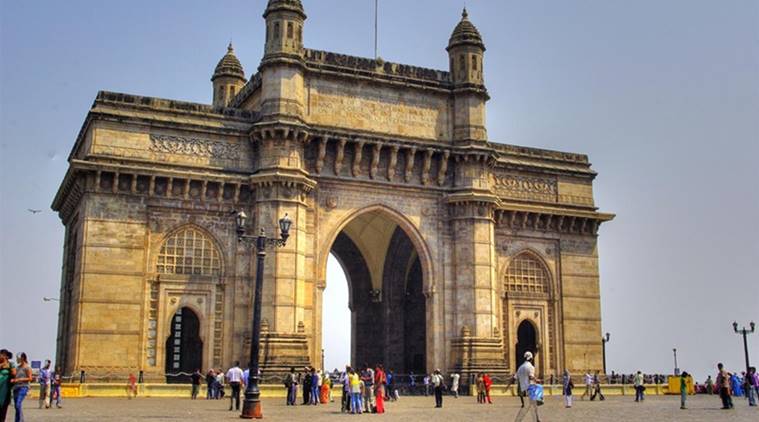

Long before the sabziwallah in Bandra (West) began to stock asparagus and artichoke, in fact, over 300 years previously, Bandra already had global aspirations, given as it were, in dowry with six other islands to a colonial prince. By history and evolution, and as much by the Mumbaikar’s sheer will, this was always a global city. Historians, conservationists, architects and Bombay chroniclers concur — the urbs prima in Indis was once the Manchester of the east, the Gateway of India, home to architecture of multiple styles — from Venetian to Gothic to Tudor to Art Deco, and home also to a people with a general savoir faire.

When July 1991 came around, Bombay was already pitching for a new growth phase, having readied its critical Development Plan 1991-2011, a 20-year blueprint for its continuing journey into global accomplishment. In fact, city planners took little note of the coming onslaught of socio-economic and cultural change.

“What was happening was at a macro-level,” says Sharad Kale, who was Mumbai’s municipal commissioner between 1991 and 1995. “State government departments would have felt the impact, but Mumbai’s municipality was not responsible for de-licencing of industries, nor for any other reform on trade.”

In fact, Kale remembers the financial capital’s Nervous Nineties as a period when the city administration was actually distracted from the tumultuous July 1991 events in New Delhi by a series of dramatic events — the riots in December 1992, a second round of riots in January 1993, the serial bombings of March 1993, and then the plague scare of 1994.

Watch Video: What’s making news

In each instance, the municipality was left to clean up, tend to the sick, attend to the dead, keep records, and help prevent a redux. There was little time to think about a cultural revolution or an infrastructural upgrade, nor for what demographic changes would follow the new wave of job-seekers in cities. “There were some ideas that were tossed around for municipal administration, such as raising funds through bonds,” says Kale, adding that Mumbai didn’t need to bite that bait. “Ahmedabad raised Rs 100 crore, and didn’t know what to do with it.”

The introduction of the Development Control Regulations in 1991, though this had nothing to do with the policymakers’ plans in New Delhi, was one of the positive highlights among the changes in urban form seen in the city after 1991, says professor Roshni Udyavar Yehuda, head, Rachana Sansad’s Institute of Environmental Architecture.

The introduction of the Development Control Regulations in 1991, though this had nothing to do with the policymakers’ plans in New Delhi, was one of the positive highlights among the changes in urban form seen in the city after 1991.

The introduction of the Development Control Regulations in 1991, though this had nothing to do with the policymakers’ plans in New Delhi, was one of the positive highlights among the changes in urban form seen in the city after 1991.

“The DC Regulations enforced a certain degree of control on property owners to comply with regulations in the larger interest of the city — including health, hygiene, access to light and ventilation, as well as parking and open spaces. Prior to this, the Bombay Improvement Trust or BIT existed to exert restraint on property developments, having been established by the British in response to the widespread and grossly unhygienic conditions during the plague epidemic in Mumbai (then Bombay) around 1895. The DCR brought in uniformity in development, urban form and sanitation seldom seen in other cities in India, and was soon to be replicated across the country.”

Meanwhile, the Shiv Sena, having already tasted power in the Mumbai municipality, came to power in Maharashtra in 1995, riding a wave of Hindutva and regional chauvinism. “In a curious way, it can be compared to what’s happening in England now, although the migration there is from across the country’s borders,” says Dr Uttara Sahasrabuddhe, professor, department of civics and politics, Mumbai University.

Having begun her teaching career in the early Nineties, and having had the opportunity to closely watch youngsters over the decades since liberalisation, Sahasrabuddhe says the fruits of economic liberalisation are undeniable and plentiful, visible in youngsters’ unprecedented searching out of opportunity, risk-taking and innovation.

However, a simultaneous response to the economic right-wing in Mumbai was the growth of the cultural right-wing, an almost inevitable fallout. Migrants became an issue in India’s most open-minded urban agglomeration. “In a way, the city’s multicultural ethos took a beating. Remember, Bombay became Mumbai then.”

The emphasis was on decongesting the city, encouraging units to move into the outback, the larger Mumbai Metropolitan Region.

The emphasis was on decongesting the city, encouraging units to move into the outback, the larger Mumbai Metropolitan Region.

The mills had closed down by then, the remaining manufacturing units in the city were on their last leg, and the workers’ movement had let out a last, wrenching cry. Kale says that the period’s priorities in industrial location were to ensure that no new industries began south of Mahim. The emphasis was on decongesting the city, encouraging units to move into the outback, the larger Mumbai Metropolitan Region.

The breaking of the textile strike of the 1980s had demoralised the labour movement, and those of the working class who were drawn to Mumbai in later years were in ever more danger of being peripheralised. The closure of the factories meant a different kind of unemployment, a “casualisation of labour”, as Sahasrabuddhe terms it, an organised workforce pushed into unorganised labour. “This was, perhaps, felt more in Mumbai, the most globalised city in India, than anywhere else,” she says.

Udyavar also points out that the seeds for a shift in housing policy were also sown in those years. The Shiv Sena went on to formulate the Slum Rehabilitation Scheme, a turning point for a city with 50 per cent of its population living in slums.

“The onus of public housing and rehousing slum population was largely taken away from the realm of the state and moved into the hands of the highly competitive and profit-oriented private real estate developers through the introduction of the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA). These changes, however, were brought in with little regard to the quality of dwellings for the poor and the rehabilitated population, resulting in eyesores…”, she says. The “vertical slums” that the SRA built remain an urban design challenge that Mumbai’s planners are still to overcome.

Sahasrabuddhe sees the failure of successive governments to plan adequately in the marginalisation of the urban poor . “We live in this nostalgia of rural India, and, as a result, not a single government till very recently took any interest in urban centres,” she says. The result, as she describes it, was “a vibrant city decaying after the 1990s.”

This played out as rapid but haphazard development — mass transportation never caught up with the need created by the ever-growing population, a higgledy-piggledy rash of roads and flyovers was laid out, a piecemeal creation of civic amenities followed, and then plan upon plan for better drains and sewers that were uniformly delayed. Alongside, there was an alarming disappearance of open spaces. By the late 1990s, the mill lands were opened up for development, each parcel housing properties more luxurious than the last, each new property unnerving and agitating the local Marathi manoos a little more.

Those Mumbaikars who shun the cookie-cutter malls and indistinguishable coffee shops as much as they wince when they see a satellite image of Deonar dumping ground ablaze — they’re the Mumbai generation the Nineties failed.

They’re easy to spot — they’ll have that tired shuffle at weekend heritage walks and citizens’ protests, for they’ve done this before. They’ll marvel at a new standalone bookstore, be the most wistful upon seeing a double-decker bus stall on a flyover, a little in denial still at how we went from British-era sewers that Amitabh Bachchan was shown splosh-striding in, to open gutters with their inky black sludge headed for the sea. They’re the ones who won’t argue when told it’s easy to blame the Nineties. They’re the ones who’ll go home knowing it’s easy not to blame the Nineties.