Huddled together in a boat with her daughters and neighbours, 71-year-old Zahida* had lost track of time. In the evening darkness, the vast expanse of the Bay of Bengal couldn’t have provided a more ominous backdrop for this group of Rohingya on a wooden boat escaping violence in Myanmar. On water, and before that on foot, their journey was long and dangerous.

From Zahida’s village in Rakhine state, it was a four-day trek before she got into a boat and reached Shamlapur Bazar in Bangladesh. “My head was spinning. I was vomiting,” she says, sitting in the relative safety of her tarpaulin tent. For the last two months, Zahida’s new address has been the Kutupalong Refugee camp extension, near Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh. Despite reports of security threats to women in the camps, this, she says, is her safe space. Her new thikaana.

“We were praying to god, clutching on to each other,” Yasmin, her daughter adds.

Their journey is the same as that of hundreds of thousands of other Rohingya women and girls, who have fled ethnic cleansing, carried out by the Myanmar military in Rakhine state. Many have stories of experiencing or witnessing brutal violence. Some do not even speak of it. Others do, avoiding eye contact, too numbed by their experience, too scared about their future.

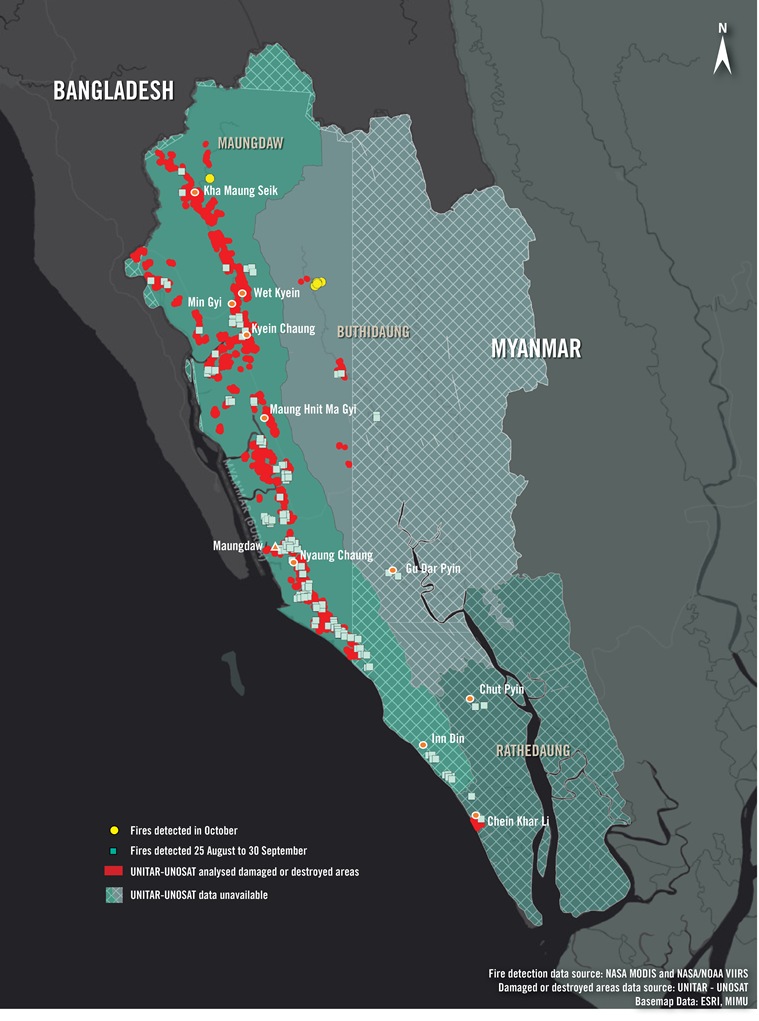

At least 620,000 men, women and children have sought refuge in Bangladesh since 25 August. State-sponsored discrimination and violence has been a constant in Rakhine state, which was home to just over a million Rohingya, a predominantly ethnic Muslim minority. A discriminatory 1982 citizenship law and its application denied the Rohingya their right to a nationality and virtually every aspect of their life is restricted by the Myanmar authorities.

Rohingya women and girls have survived sexual violence, including in some cases being raped by the Myanmar military. Many have witnessed killings, violence, and the burning of their villages. Jamila, a 25-year-old new arrival at Kutupalong, who escaped from Myanmar with her husband and children, starts to tremble at even the mention of the word ‘military’.

Accounts of sexual violence documented by Amnesty International in its report ‘My World is Finished’ are acutely distressing. Testimonies of survivors interviewed in Bangladesh made it clear that the sexual violence in August and September 2017 fit a pattern of soldiers targeting Rohingya women and girls in northern Rakhine State, including during the military’s clearance operations in late 2016. It is difficult to ascertain the scale of sexual violence. In many situations sexual violence is underreported because of the associated fears, stigma and cultural attitudes towards women.

One woman told Amnesty International how she and four other women were taken in by four soldiers in a Rohingya house. All the women were stripped naked, beaten and raped. Then the soldiers set fire to the house. For the survivors in Bangladesh, it was evident that comprehensive health care and trauma counselling was urgently needed, in addition to adequate support to live in dignity.

None of the women we spoke to placed any hope in the possibility that the violence would stop in the near future. Even refugees who fled Rakhine years ago don’t want to return yet. Momtaz, another 50-year-old Kutupalong camp resident, who escaped to Bangladesh in the nineties from Myanmar, says this exodus brings back memories of her earlier attempt to find a life worth living. “The atrocities in the 90s were also extraordinary. The military would take our men inside the forest and they would not come back. They would rape women,” Momtaz said. In 1991 and 1992 over 250,000 Rohingyas fled to Bangladesh following widespread forced labour, summary executions, torture including rape, and arrests on religious and political grounds.

Mumtaz says firmly, “I am staying where the [Bangladeshi] government has given us land. I don’t want to go anywhere. My husband also died here and I will also die here.” Momtaz is clear that returning to Myanmar is a complete no for her.

For many Rohingya people, the fear of coming face-to-face again with what they escaped, is becoming even more of a reality across the border in India, where the government is trying to expel an estimated 40,000 Rohingya in the country.

Photo courtesy: Amnesty International

Photo courtesy: Amnesty International

As diplomatic channels, international pressure and rights groups keep a watch on the situation of the Rohingya, what Zahida remains grateful for is that she escaped death. Paying the boatmen is often the only way to get to the relative safety of Bangladesh. Although some refugees have complained of extortion by boatmen, Zahida remains grateful to the man who ferried her to safety. “We didn’t have money to pay him. We were carrying a little bit of jewellery we had, tied in tiny cloth pouches. It was the good boatman who directed us to a person he knew to sell our jewellery to. Once we got the money and paid the boatman, he got us here.”

In Bangladesh today there is an imperative need to provide more than a sense of safe space for Rohingya women and girls to pick up their lives the way they want to. To heal. Most importantly, they and other Rohingya refugees should not be forced back to Myanmar. The Rohingya must be allowed to decide whether and when they wish to return.

While the violence still continues, and the conditions to return in safety and dignity are not yet in place, any measures towards returning Rohingya refugees to Myanmar are premature.

#GenderAnd is dedicated to the coverage of Gender across intersections. All names have been changed to protect identity. Read our work here