A room without a view: Snapshots of Swiss Army bunkers converted to hotels

For upwards of almost $200 a night, guests at a Swiss hotel might expect to catch a glimpse of the towering Alps or overlook one of the country's famous lakes. But visitors to Hotel La Claustra get a room without a view. The 17-room hotel is buried in the Gotthard mountain range and, with cavernous walls and minimalist interior, offers the chance to spend a few nights in an ex-army bunker.

January 19, 2016 00:30 IST 1 / 19

1 / 19For upwards of almost $200 a night, guests at a Swiss hotel might expect to catch a glimpse of the towering Alps or overlook one of the country's famous lakes. But visitors to Hotel La Claustra get a room without a view. The 17-room hotel is buried in the Gotthard mountain range and, with cavernous walls and minimalist interiors, offers the chance to spend a few nights in an ex-army bunker. (Text: Arnd Wiegmann, Source: Reuters)

2 / 19

2 / 19There is a bleak brick entrance, decorated only with a Swiss flag. (Source: Reuters)

3 / 19

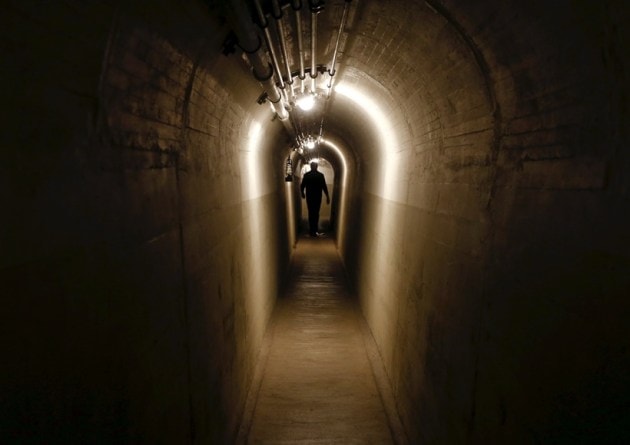

3 / 19Inside, a restaurant, windowless rooms and lounge are all hacked from the bare, surrounding rock. (Source: Reuters)

4 / 19

4 / 19La Claustra is part of a wider trend in Switzerland for recycling the plentiful decommissioned bunkers first carved out to defend the famously neutral country from foreign invasion. (Source: Reuters)

5 / 19

5 / 19From data centres to museums, from mushroom farms to cheese factories, businesses have been refashioning the former strongholds. (Source: Reuters)

6 / 19

6 / 19During World War II, Switzerland had a network of around 8,000 bunkers and military shelters. (Source: Reuters)

7 / 19

7 / 19Faced with high maintenance costs and a cooling threat of invasion, the Swiss army — since the 1990s — has handed a property unit the task of trimming that number down. (Source: Reuters)

8 / 19

8 / 19"Along with our processors, our key selling points are the Swiss brand and the physical safety of this bunker," said Frank Harzheim, managing director at Deltalis data centre, located in a bunker that once housed up to 1,500 soldiers. (Source: Reuters)

9 / 19

9 / 19The vast majority have now been bought, sealed off, or set aside for historical preservation and are dotted around Switzerland — often still disguised as barns, houses and medieval castles. (Source: Reuters)

10 / 19

10 / 19According to one possibly apocryphal story repeated with pride for more than a century, Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II — on a visit in 1912 — was said to have asked a Swiss infantryman what 100,000 Swiss soldiers would do if 200,000 German invaders stormed over the border. (Source: Reuters)

11 / 19

11 / 19"Each would have to shoot twice, your majesty," came the supposed reply. (Source: Reuters)

12 / 19

12 / 19Museums like Sasso San Gottardo — built in a former fortress — look to tell the story of Swiss efforts to stave off invasion in the 20th century. (Source: Reuters)

13 / 19

13 / 19After Germany invaded France in 1940, Switzerland was surrounded by Axis powers and recognised that it would be out-gunned in any assault. (Source: Reuters)

14 / 19

14 / 19To hold off an invasion, Switzerland sought to make itself prohibitively difficult to conquer. (Source: Reuters)

15 / 19

15 / 19Under the plan dubbed the 'National Redoubt', much of the country's manpower and firepower would retreat to the mountains if a foreign aggressor attacked. (Source: Reuters)

16 / 19

16 / 19Through its chain of fortresses and bunkers, Switzerland would keep control of the mountains along with key transit routes. (Source: Reuters)

17 / 19

17 / 19"This was a pragmatic solution, but also a very problematic one," said Rudolf Jaun, a former Swiss history professor at Zurich University. "The Redoubt strategy was what we call in German a 'Notloesung' — emergency solution." (Source: Reuters)

18 / 19

18 / 19During the Cold War, concerns turned to nuclear attack. The Swiss ramped up military spending and many homes were required to be equipped with bomb shelters. (Source: Reuters)

19 / 19

19 / 19As with the bunkers, the Swiss have found new uses for these bomb shelters too — nowadays many are simply used to store family knick-knacks and wine collections. (Source: Reuters)