In Tamil Nadu’s starless wars, a sun and assorted satellites

The mother of all alliances this time is the motherless AIADMK’s. Minus Jayalalithaa, who projected herself as PM in the 2014 elections, the ruling AIADMK is seen by critics as BJP’s satellite.

The colour of the campaign seems to match the reduced stardom.

The colour of the campaign seems to match the reduced stardom.

The oldest of Tamil voters wouldn’t remember an election like this. The state has for long voted stars and superstars. Stardom came not just courtesy cinema or cinema-driven Dravidian politics. Right back in the Nehruvian nationalist era, people here saw the Indian National Congress as Kamaraj Katchi (party). Now, having lost both J Jayalalithaa and M Karunanidhi in quick succession over the last couple of years, the electoral skies look suddenly blank. “There is a sun and some assorted satellites,” quips a longtime watcher of Tamil politics.

Click here for more election news

DMK’s symbol, the rising sun, no longer represents the frozen state of the successor-in-waiting. The son has finally risen. At 66, Stalin is the dominant image on posters and banners but the party’s voice is still Karunanidhi. Along the highway from Tirunelveli to Tenkasi you hear wayside loudspeakers blasting out paeans to “Kalaignar”. But his famously rousing speeches are not being replayed. That would call for some diligent editing. Across a chequered career of electoral partnering, he would seem embarrassingly flexible in retrospect.

The mother of all alliances this time is the motherless AIADMK’s. Minus Jayalalithaa, who projected herself as PM in the 2014 elections, the ruling AIADMK is seen by critics as BJP’s satellite. And Amit Shah showed he can shoot down a not-friendly-enough satellite. Within days of tying up the alliance, he rephrased the arrangement squarely as NDA and not an AIADMK-led front. Contesting from just five out of 40 Tamil seats, including Puducherry, BJP here is punching way above its weight.

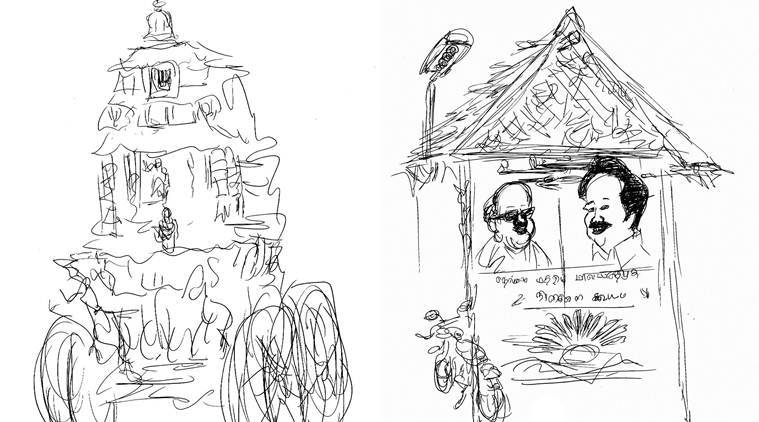

If Election Commission has its way, the temple chariot would look as colourless as this

If Election Commission has its way, the temple chariot would look as colourless as this

The colour of the campaign seems to match the reduced stardom. A full hundred kilometres into Tamil country, through some much-peopled towns and villages, there wasn’t a single sign of election. And when it came, it was the barricade where central forces were stopping vehicles to check for cash and whatever else that tempts the voter. At Chengottai, outside the road transport corporation office, the multiple notice-boards of trade unions have been wrapped up to keep any sign of multi-party democracy out of sight.

READ | In first poll without Big 2, how patchy tie-ups may backfire

At a bleak dusty cluster of identical houses ironically called Rainbow Colony in Vannarpettai, in suburban Tirunelveli, the DMK’s local office is recognisable thanks to a single poll banner stretched across as backdrop to an open thatched conference room that doubles as parking lot for two-wheelers. It can’t get more austere than this. The new regional factor that threatens to boom, Dinakaran’s AMMK (Amma Makkal Munnetra Kazhagam) has just got its symbol allotted, a gift box that should come wrapped in permitted colours. The biggest splash sighted was the deep red on an MLA’s open jeep that displays an Election Commission permit restricting the vehicle’s movement to the constituency.

DMK local office at Rainbow colony

DMK local office at Rainbow colony

But then, politicians can be trusted to find a way out. They are outsourcing colour without having to account for it. BJP’s Tamilisai Soundararajan joined festivities that included the ritual pulling of a temple chariot in Thenthirupper. The non-Toyota rath at the Vishnu Mandir decked up in flowing festoons was enough to make up for the deprivation elsewhere.

Across the landscape dotted with windmills and cell phone towers, the recurring presence is the child in school uniform. Early evening, walking or cycling from school and when night falls, on two wheelers being ferried back home from coaching classes for entrance tests. Abolition of NEET (National Eligibility cum Entrance Test) is a poll promise in Dravidian manifestos. The 18-year old Shanmugam Anita who scored high in her qualifying state board exam and lost the entrance test ended her life in September 2017. Since then the all–India test is just about as popular in these parts as the Uniform Civil Code is in Kashmir. Among others, there is a parental vote block to watch out for.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05