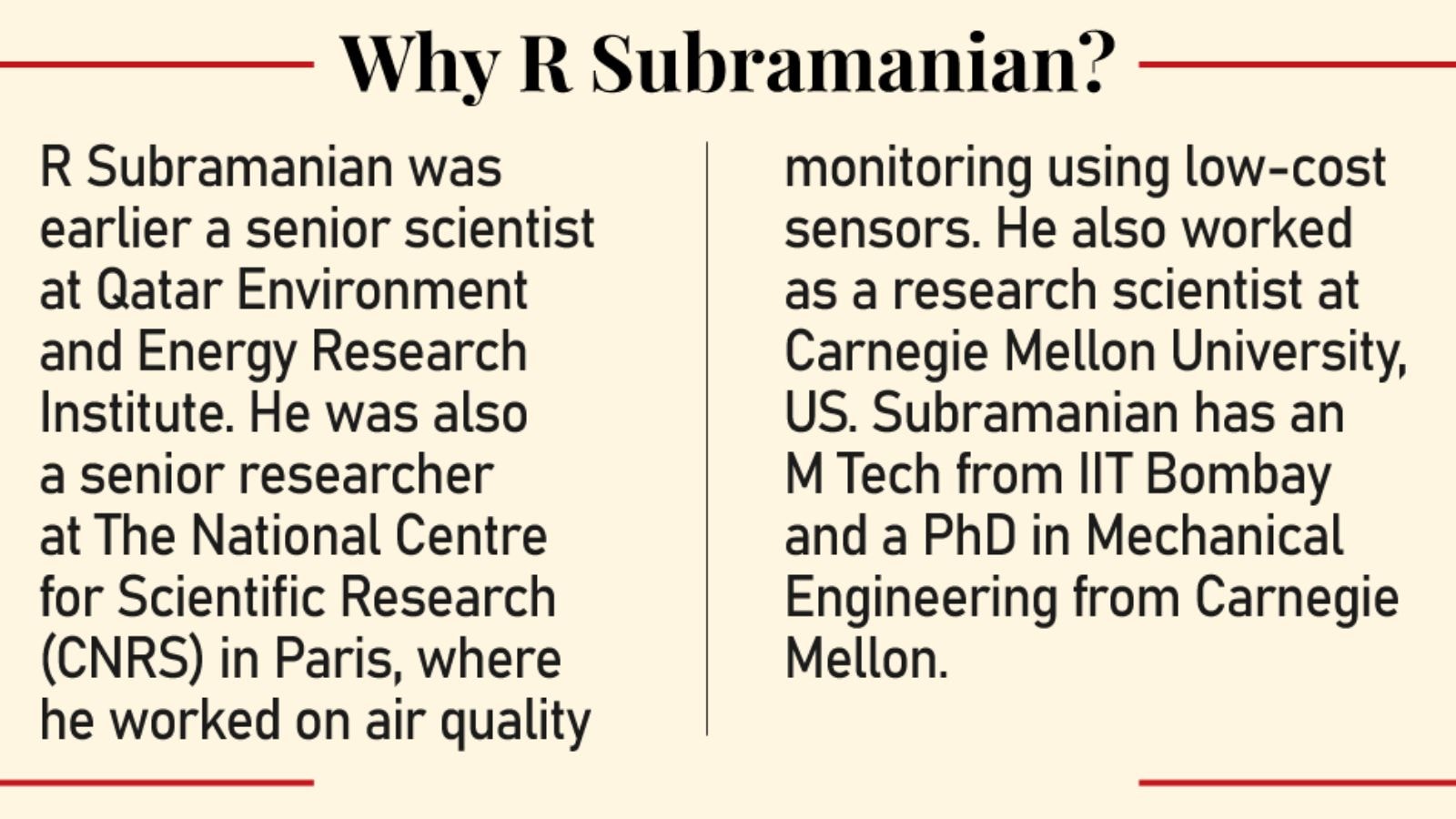

Tech for predicting air quality has matured, should be used more: R Subramanian, air quality scientist, CSTEP

CSTEP seeks to enrich policymaking with innovative approaches using science and technology.

R Subramanian, Air Quality expert, CSTEP. (Express photo by Jithendra M)

R Subramanian, Air Quality expert, CSTEP. (Express photo by Jithendra M)There is a need to predict air quality and take action rather than wait for an incident to happen, says R Subramanian, Sector Head (Air Quality), Center for Study of Science, Technology and Policy (CSTEP), a leading Bengaluru-based think tank in the energy transition and clean air sector.

CSTEP seeks to enrich policymaking with innovative approaches using science and technology. Using tech such as low-cost sensors, mobile monitoring, and satellite-based monitoring of air pollution, CSTEP is working on making data on air pollution robust, easily available and provides inputs for policy makers.

Subramanian spoke to indianexpress.com on the need for affordable sensors to monitor air quality at a more granular level in India’s cities and towns, the new startups and technologies in the sector, and the need to predict air quality. Edited excerpts:

Venkatesh Kannaiah: Is air quality mitigation/betterment a tech issue or a governance/policy issue?

R Subramanian: It is both a tech and a governance/policy issue. The third facet in India is that it is also a societal/behavioural issue. In India, we have multiple sources of air pollution, including residential combustion — where households use fuel to cook, heat or cool their homes — urban transportation, formal and informal sector. Some of it could be changed by tech interventions and some by policy changes but some of it would necessarily require a behavioural change.

Venkatesh Kannaiah: How well covered are we with air quality monitoring sensors or stations in India? There is also a discussion on affordable/low cost sensors. Can you elaborate?

R Subramanian: In India, Tier 1 cities are fairly well covered with air quality monitoring sensors. Tier 2 and 3 cities are not covered much, and in rural areas there is a huge gap. What we are referring to are reference grade monitors which are of high quality and there are around 500 of them across India.

To put it in perspective, say a city like Bengaluru would have 10-12 of these while some cities in Europe, like say London, might have 100 of these tracking stations. It might sound a bit excessive, but London, which already has around 100 reference grade monitors, is experimenting and collecting data with 400 low-cost sensors through its Breathe London programme. But other cities, like say Paris, might have only around 15 reference grade monitoring stations. Even in smaller cities like Pittsburgh in the US, where I worked earlier, there are five reference grade stations for a population of six lakh people. Our research team deployed a network of 50 affordable sensors in Pittsburgh in addition to the earlier five. A lot of cities in the US and Europe are deploying sensor networks in addition to the government reference monitors.

In cities, the primary objective would be to track emissions from vehicular traffic.Many cities are experimenting with affordable low-cost sensors to increase the range and to get granular level information on air quality.

These reference grade stations and monitors need to be maintained at a particular temperature and the equipment needs to be calibrated almost on a weekly basis. It costs around Rs 1- 1.5 crore per station to set it up, leave alone the maintenance. The sensors cost around 5 lakh, are more robust, do not need to be always at a particular temperature, and are exposed to the vagaries of the weather. There are software and other algorithms which can run on the data that these low-cost sensors provide, and which can remove the distortions or discrepancies if any, and provide fairly indicative air quality data for cities.

However, monitoring for particulate matter — a mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets found in the air — is different. Particles less than 10 micrometres in diameter (PM 10) can get deep into your respiratory system and some may even get into your bloodstream. Of these, particles less than 2.5 micrometres in diameter (PM 2.5) can reach your lungs and pose great risk to health.

In India, the low-cost sensor tech for tracking PM 2.5 is already available and in use. There are now integrators who buy this tech from abroad and repackage it and sell it in India. We are piloting a study with funding from Google and have installed 45 low-cost sensors across Bengaluru to test PM 10 sensors and gas sensors. We are testing the equipment of various manufacturers and evaluating it, with the goal of finding their utility and applicability for Indian conditions. We are likely to showcase the results of these tests at our next Indian Clean Air Summit in Bengaluru , due in the last week of August.

Subramanian spoke to indianexpress.com on the need for affordable sensors to monitor air quality at a more granular level in India’s cities and towns, and more.

Subramanian spoke to indianexpress.com on the need for affordable sensors to monitor air quality at a more granular level in India’s cities and towns, and more.

Venkatesh Kannaiah: Can you tell us about 3-4 emerging innovations or technologies which could impact air quality going forward?

R Subramanian: You must understand that some technologies or innovations like smog towers have not worked in India. Air purifiers too work at home or offices and in controlled environments,-they do not work outdoors. After all, it might have an efficacy of around 50 metres. So controlling pollution at source is the only option in India.

Some work has already been done. Bharat stage (BS) emission standards are laid down by the government to regulate the output of air pollutants from internal combustion engine and spark-ignition engine equipment, including motor vehicles. We have moved from BS-IV to BS-VI, and it is quite a bold step. The large-scale movement towards LPG has reduced the burden on air quality, but it is with the usage of electric stoves that we will see better results. There are policy changes on scrapping of old vehicles and on reducing cooking emissions. Policies on agri residues and waste burning are also welcome. But the key is to make it attractive for startups to work on agri residues. It could be a logistics issue, but if sufficient market incentives are there, it would be taken up.

Indian Oil Corporation’s solar powered electric stove is one of my favourites when it comes to emerging innovations in this sector.

Venkatesh Kannaiah: Can you name a few interesting startups in the air pollution/air quality space?

R Subramanian: There are some startups working in the agri residues space, like Craste, which purchases crop residues from farmers and recycles them into packaging material. It repurposes crop waste into moulded packaging, paper products and particle boards, and also helps farmers make additional revenue. It tackles air pollution at source, even before it is generated.

There is Rondo Energy, based out of the US, which repurposes renewable energy into heat batteries. Industries can purchase the Rondo Heat Battery for their facilities and the company offers Heat as a Service (HaaS) to deliver low and predictable power costs, without upfront capital. The heat battery is modular, scalable, and energy dense. This method offers a fast, low-cost pathway to decarbonisation and reduced operating costs.

Venkatesh Kannaiah: Globally, what are the themes/areas that air quality startups work on?

R Subramanian: There are many startups working in different areas relating to air quality. Some work on providing filters on split air conditioning at home, some claim capturing of CO2, and some are into retrofitting diesel generator sets.

There are three areas where startups are working. First is on source control of emission, say diesel particulate filters. Some like Craste work on even preventing emissions in the first place. Second is the air quality monitoring arena with sensors and new innovations in low-cost sensors. There are also data science startups, which work on collating satellite and ground data and use it for air quality forecasting. It is quite useful for companies which depend on such data. The third would be those which control pollution at the end point, say the indoor air quality at your home or workspace.

Globally, the focus is on tech for curtailing carbon dioxide emissions at source and the move towards solar powered EV charging. We at CSTEP also have a solar powered EV charging pilot going on in Bengaluru and it is working very well.

When people talk about clean tech, they talk about CO2 emissions and investments are directed towards the same. Air pollution is not the focus.

Venkatesh Kannaiah: With your global experience, can you tell us about interesting tech plus community interventions with regard to air quality that have worked?

R Subramanian: We had an interesting experience in Pittsburgh. There was a community intervention at a steel industry plant, wherein due to the pollution from the coke production facilities, the community groups got together to install a camera on the facility to track the belching of the smoke and it finally led to the closure of the plant. In another related issue, there were two steel plants in close proximity and due to certain specific wind flow patterns in the region, the pollutants from one part of the city would reach the other part and would create a health issue. This was monitored and resolved in a way that when such wind patterns develop, the steel plant outside the city was made to go slow on its production and thereby manage the pollution that was being generated. This was an interesting case of substantial citizen engagement and community intervention leading to changes on the ground. This is also to do with prediction of air quality based on wind flows.

For example, the Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) is a framework designed to combat air pollution in the Delhi-NCR region. It was introduced as an emergency response mechanism and its implementation is triggered when the air quality reaches ’poor’ levels. We definitely need to move towards prediction of air quality flow rather than wait for the event to happen and then take action. We could use modelling, computational fluid dynamics, and also use AI to make these air quality predictions faster and better.

Venkatesh Kannaiah: Can you tell us your work on a clean air action plan for 70 cities and its progress?

R Subramanian: We have done an emission inventory study, including detailed sectoral emissions for around 76 cities across the country. We also have recommendations for mitigating the issue, which we will unveil at the forthcoming India Clean Air Summit. Based on this report, we will work with various city governments on air quality. We also hold regular capacity building workshops for city leaders on air quality.

“n India, Tier 1 cities are fairly well covered with air quality monitoring sensors. Tier 2 and 3 cities are not covered much, and in rural areas there is a huge gap,” Subramanian said.(Express photo by Jithendra M)

“n India, Tier 1 cities are fairly well covered with air quality monitoring sensors. Tier 2 and 3 cities are not covered much, and in rural areas there is a huge gap,” Subramanian said.(Express photo by Jithendra M)

Venkatesh Kannaiah: What is the focus of your forthcoming India Clean Air Summit 2024, and what learnings from earlier summits have been implemented on the ground?

R Subramanian: India Clean Air Summit (ICAS) 2024 is a flagship air quality event of CSTEP. The sixth edition of ICAS is based on the central theme of the Participatory Future of Air Quality Management to drive collaborative action on air pollution in India and will be held from 26-30 August.

This platform provides an opportunity for countries in the Global South, such as India, Ghana, Rwanda, Kenya, and Nigeria, to gain insights from successes in the global North countries and from each other.

We will also look at applications to identify neighbourhood-scale pollution hotspots, fill in data gaps in rural or unmonitored regions where little to no monitoring infrastructure exists, facilitate fence-line monitoring of industrial emissions, and improve air quality at home and workplaces.

Venkatesh Kannaiah: If you were to bet on three tech interventions, for solving the air quality issue in India, what would they be?

R Subramanian: I would be betting on Indian Oil Corporation’s solar powered electric stoves, startups that work on preventing burning of waste either as agri residues or solid waste management issues in cities, and finally, those which work with industries to produce solutions of supplying renewable power for industries.