The thick gray walls of the Holy Trinity Church near Turkman Gate in Old Delhi are adorned with fairy lights days before Christmas. Inside, two young men are busy planting Christmas wreaths, ribbons, stars and Santa figures on the walls, while two middle aged women sit down to sort out satin flowers to decorate the church pews.

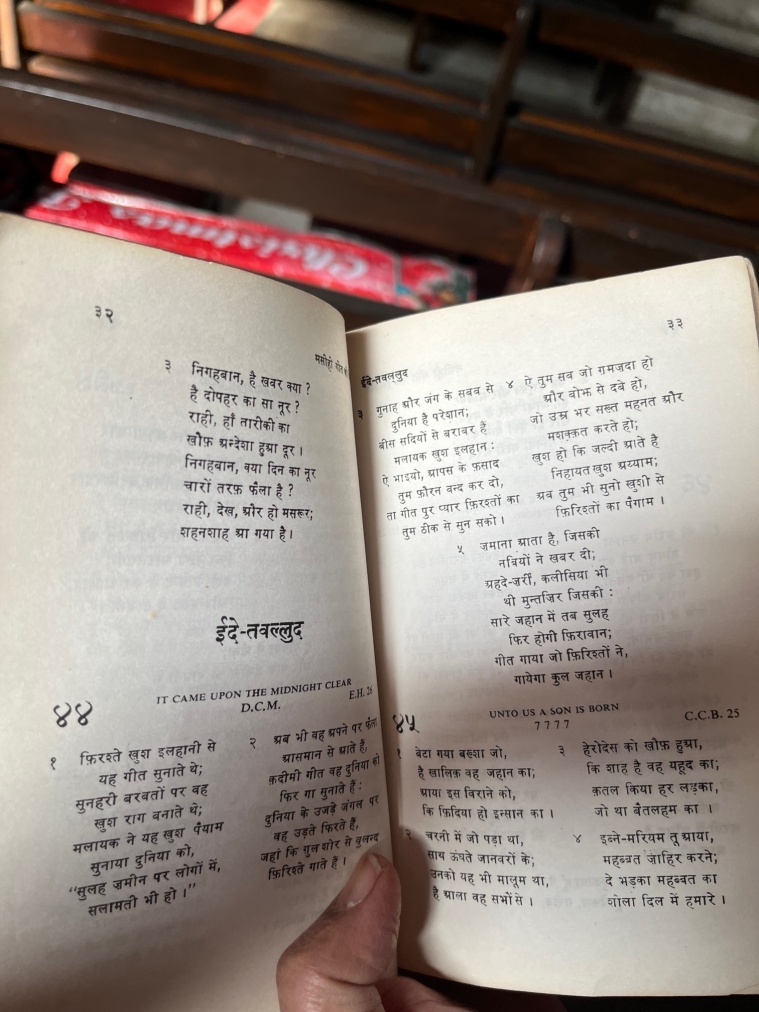

Reverend Joel I Lazar picks out an aging book of hymns from one of the shelves inside the church to speak about his favourite Christmas carols. “Most of our carols are in Hindustani. It is a mix of Hindi and Urdu,” says Lazar. ‘Eid-e-Tawallud’, one of the hymns he points to, translates as the ‘celebration of the birth (of Jesus)’. “It is common here to refer to Christmas as ‘Eid’, ‘Eid-e-wiladat’ which means celebration of the birth, or ‘bada din’,” he explains about the unique ways of the Christian community that lives in and around the church that stands on the southern border of Old Delhi. The Turkman Gate church along with the Central Baptist Church in Chandni Chowk, are the only two churches remaining in the historic city of Shahjahanabad that continue with the tradition of holding services in Hindustani, and celebrating a Christmas with strong imprints of a Mughal era gone by.

Eid-e-Tawallud translates as the celebration of the birth of Jesus (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

Eid-e-Tawallud translates as the celebration of the birth of Jesus (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

In the multicultural mishmash of Old Delhi, there exist a few small but thriving pockets of the Christian community. Although many among them are descendants of migrants who came to Delhi from other parts of India decades ago, the Christian connection with Shahjahanabad goes centuries back when Armenians and the Portuguese became the first to make this quintessential Mughal city their home.

The earliest Christians of Old Delhi

It is widely known that the first Jesuit mission to set foot in India was that under St. Francis Xavier in 1542 in Goa. It was only much later in 1580 that a Jesuit mission reached the Mughal capital of Fatehpur Sikri on Akbar’s invitation. While the Jesuits did enjoy patronage under Akbar and Jehangir, securing permission to build schools and churches in Agra and Lahore, under Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, that seems to have worn off by the time Shah Jahan came to power and shifted his capital to Delhi in 1648.

Nonetheless, given Delhi’s reputation as a hub of trade and commerce under Shah Jahan, it was not uncommon for people from communities far and wide to visit the city or establish livelihood here. Some of the earliest Christians we hear of in the city were the Armenians. Historian and author Swapna Liddle says that the Armenian merchants were an important group and were perhaps numerous enough to have a church with a priest, Rev. Stephanus, who is mentioned as living in the city in the early 18th century.

The well known chronicler of Delhi, RV Smith, in his book ‘Delhi: Unknown tales of a city’ (2015), notes that the Armenians came to India during the reign of Akbar and settled mostly in Delhi and Agra before finding a new home in Calcutta. Smith writes that in the Mughal bastions, the Armenians, all of whom were Christians, held high posts in the court and that one of them, Abdul Hayee, even became chief justice. He also chronicled that one of the Catholic churches built by the Armenians existed near the Subzi Mandi and the other near a slaughterhouse which was destroyed during Nadir Shah’s invasion in 1739. He writes that “Kishanganj, between Old Delhi and Sarai Rohilla stations, has a cemetery where some notable Armenian and Dutch members of the royal court at Red Fort are buried.”

There was also the notable Portuguese presence of Julian Dias da Costa who came to the Mughal court from Kochi. How she came to Delhi remains unclear. One account suggests that her father, a physician named Agostinho de Dias Costa, was brought to Delhi as a slave after Shah Jahan’s army destroyed the Mughal settlement in Hooghly. There is another story that suggests that the family fled to Delhi after Kochi fell to the Dutch. Juliana though is known to have been born in Delhi and in fact became very rich and powerful in the Mughal court. She is known to have been appointed governess to some of Aurangzeb’s children. Later she was allotted a piece of land to build a sarai (traveller’s inn) of her own, in the area that we today know as Sarai Julena in New Friends Colony.

Story continues below this ad

Juliana Dias Da Costa was allotted a piece of land to build a sarai (traveller’s inn) of her own, in the area that we today know as Sarai Julena in New Friends Colony. (Express Photo by Amit Mehra)

Juliana Dias Da Costa was allotted a piece of land to build a sarai (traveller’s inn) of her own, in the area that we today know as Sarai Julena in New Friends Colony. (Express Photo by Amit Mehra)

Another well known name from the same family was that of Manuel D’ Eremao. He along with his son and nephew were part of the Maratha army in the late 18th century. He is known to have built a beautiful haveli in the Maliwara neighbourhood of Old Delhi. Liddle explains that its grand gateway still exists bearing a name with some connections that of Manuel D’ Eremao: Manmahal ki Haveli. “During the Anglo-Maratha war the East India Company sent out overtures to them with promises of handsome returns and pensions if they were to come on the British side,” says Liddle.

The British took control over Delhi after defeating the Marathas in the Second Anglo-Maratha war of 1803. It ushered in a new phase of missionary activities in the city. Historian and researcher Moon Moon Jetley in her book, ‘The Calm and Storm in Delhi: 1803-1857’ (2015) writes that “when the British took over Delhi the Jesuits had not left behind a continuing Christian community behind”. The two Roman Catholic churches were in ruins.

The work began by Protestant Missionary Societies too, however, was not as successful as they were perhaps in other parts of the country where the British had a stronghold. A Baptist Society was founded in Delhi in 1818 under the leadership of John Thomas Thompson from Serampore. “The mission was in a very weak position and failed to make any impact in the city,” writes Jetly. She adds that “during his tenure in Delhi he did nothing much except open a small mission school in the city for low caste families. Although he shared an amicable relationship with staff members of the Delhi College, the College remained unaffected by his Christian discourses.”

There were also some evangelicals such as Henry Martyn who made some serious efforts at carrying out missionary activities in the region. Martyn was a military chaplain in the East India Company and he came to Calcutta in 1806. Jetley writes that it was “Martyn’s first Urdu translation of the New Testament which began to be disseminated from Calcutta that was about to create a sensation in the years to come.” She explains that it was through Martyn’s work that the Ulama came to be acquainted with Christianity. Jetley notes that Martyn’s teachings also inspired a Delhi youth by the name of Sheikh Salih to convert to Christianity. Salih was born in Delhi in the 1760s to an Ashraf Muslim family. “He was the first significant Muslim convert to Protestant Christianity in this region and was baptised as early as 1811,” Jetly writes.

Story continues below this ad

But largely the Muslims and the Christian missionaries in the city did not have a very amicable relation. “The Christian presence was making the Muslim community quite uneasy since till then they were the ruling class. Apart from the growth of missionary activities, the British residency in Delhi was trying to bring in a new kind of culture and Persian was also being replaced by Urdu and English,” says Jetly.

The anxiety caused by the Christian missionary presence quite evidently came to a boil during the revolt of 1857. Historian William Dalrymple in his book “The Last Mughal” (2006) writes that “…the Uprising was overwhelmingly expressed as a war of religion, and looked upon as a defensive action against the rapid inroads missionaries and Christianity were making in India, as well as a more generalised fight for freedom from foreign domination.”

The largest number of Christian converts came from the Hindu lower caste communities. The area around Turkman Gate where the Holy Trinity Church stands was the site where a sizable population of Dalit Christian converts were settled. Historian John C B Webster in his article ‘Varieties of Dalit Christianity in North India’ writes that the historical roots of the Holy Trinity Church go back to evangelist work of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in the Chamar bastis of Delhi and its neighbouring villages from the 1860s onward.

In 1883, these Anglican missionaries purchased four sites on which to settle their Chamar converts, one of which was the area near Turkman Gate. In 1905, the beautiful Byzantine style church was built there. Today, while most of the original inhabitants of the area have migrated, a small close-knit Christian community continues to exist around the church, giving it the popular name, “Christian colony”.

Story continues below this ad

The Holy Trinity Church next to Turkman Gate (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

The Holy Trinity Church next to Turkman Gate (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

There were also a very small number of Hindu upper castes who converted to Christianity during this period, causing quite a stir in Delhi. As Liddle explains, these were people who converted out of personal conviction. Prominent among them were Chiman Lal, one of Bahadur Shah Zafar’s personal physicians and Master Ramchandra, a teacher of Mathematics at Delhi College. Both of them came from the Kayastha caste and were converted by Reverend Midgeley John Jennings who worked as a chaplain in Delhi from 1852. In his book, Dalrymple writes that Jennings was extremely unpopular among the people of Delhi and more so after the conversion of Lal and Ramchandra. “Jennings was personally responsible for convincing many people of Delhi that the Company intended to convert them, by force, if necessary,” he writes.

The converted faith of Chiman Lal and Master Ramchandra was in fact the cause of much trouble to them during the revolt of 1857. While Lal was killed on the morning of the uprising, Ramchandra managed to escape the city. When he returned after the fall of Delhi to the British, he was hopeful to be welcomed by his fellow Christians. But yet again he found himself betrayed, living in fear and being attacked by the British on account of his skin colour.

Most of the Europeans living in Delhi in the 19th century were clustered in the posh bungalows of Civil Lines and in Kashmere Gate. The St. James’ Church at Kashmere Gate was built specifically for the purpose of catering to the elite and high officials among the Europeans, including the Viceroy who attended services in the church until the Cathedral Church of Redemption came up in New Delhi.

The St. James’ Church at Kashmere Gate (Wikimedia Commons)

The St. James’ Church at Kashmere Gate (Wikimedia Commons)

The St. James’ Church was built in 1836 by James Skinner, a very interesting figure in Delhi’s history. His father was a Scottish military adventurer and his mother was Indian. He was raised a Muslim and had joined the Maratha army as a mercenary soldier. Later, he joined the forces, but his position was complicated on account of his mixed parentage. Skinner is known to have built the St, James’ Church through his personal expense, in an attempt to fit into British society. It was during the church’s consecration, in fact, that he and his three sons were confirmed in their Christian faith. At present, the St. James’ stands as the oldest worshiping church in Delhi, with a membership of around 1200 people spread across the city and the world.

Story continues below this ad

An Old Delhi style Christmas

Paridhi David Massey recollects the many ways in which the Christmas celebrations of her childhood days in Old Delhi had its own special flavour. The 33-year-old who moved out of the walled city a few years back after getting married, had grown up living in a house on the compounds of the Central Baptist Church in Chandni Chowk where her grandfather served as its first priest for 55 years. She explains that the Central Baptist Church where she grew up and the Turkman Gate church had a very distinct Mughal influence in them, be it in terms of the language being spoken, the carols being sung or in the food being served.

Illuminated view of Central Baptist Church at Chandni chowk on the Eve of Christmas Day. (Express Photo by Praveen Khanna)

Illuminated view of Central Baptist Church at Chandni chowk on the Eve of Christmas Day. (Express Photo by Praveen Khanna)

The insides of both these churches carry inscriptions in Urdu and Hindustani and the service too is held in the same languages. “We call the Godfather, “khuda baap”, holy spirit is “pavitra aatma” and Jesus is “Ishu Massey”,” says Massey. She speaks fondly of the carol parties held in their homes ahead of Christmas and her favourite carols, all of which were in Hindustani, such as

“Dekho massey aaya zameen pe, khushi hoti hain saari qayanat”

(the entire universe is happy because Jesus is born on earth),

“Aaya maryam ka beta, dekho teen raja purab disha se aaye hain unko gift dene ke liye”

(the son of Mary is here and three kings from the east have come to give his gifts).

Story continues below this ad

The popular English carols would often be translated into Hindustani as well. Silent night for instance, was sung as “Shanti raat, pyaari raat”. The musical instruments accompanying these songs were dholaks, manjires, along with a beautiful old piano inside the church.

Massey says there were a few Punjabi Christians coming to the church as well, who would sing the carols in Punjabi. A popular one she recollects was

“Asi rab te bandeya hain, rab sanu pyaar karda hain”

(We are the sons of God and he loves us).

“These linguistic diversities kept the church alive,” she says.

Kamlesh Jacob (83) who grew up near Turkman Gate says one of her fondest memories of Christmas eve was going about the neighbourhood carol singing with her friends. “People would open their homes for us and offer us something to eat or drink,” she recollects. “Not all of these were Christian homes.”

Jacob is a first generation Christian. Her father, who was from Rajasthan, converted to Christianity after being adopted by a Christian lady when he was 12. She says growing up at Turkman Gate, they were surrounded mostly by Hindus and Muslims, but that never mattered to anyone, especially when it came to celebrating their festivals together. “During Diwali for instance we would put out diyas, and on Eid we would go to our friends’ home for biryani and sewai,” she says.

Story continues below this ad

Author Madhulika Liddle, in her recently edited book ‘Indian Christmas’, writes: “Christianity may have come to much of India by way of missionaries from Europe and America, but that does not mean the religion remained a Western construct. By no means; Indians adopted Christianity, but made it their own.”

This was true for the way in which the Bible and hymns were translated and how the churches and Christian figures were adorned in sarees and mango leaves. “Our ways of celebrating religious festivals carried, still a hint of what we knew from our cultures,” writes Liddle.

Inscription in Urdu inside the Holy Trinity Church (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

Inscription in Urdu inside the Holy Trinity Church (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)Nowhere was this as visible as it came to Christmas food in Indian Christian homes, which she writes must have been what their families feasted on back in the days when they celebrated Holi and Diwali rather than Christmas and Easter.

The Christmas ‘pakwan’ of Old Delhi consisted of the gujiyas, namakparas, shakkarparas, and bajre ki tikiyas. Father Lazar says on the morning of Christmas Day, kachoris are made for breakfast, while a grand Mughlai feast is prepped for lunch.

Story continues below this ad

Jacob recollects that lunch at her home on Christmas Day always consisted of pulao, korma, and zarda (a Mughlai sweet rice dessert). The menu has remained much the same all these years, even after she moved out of Old Delhi to her current home in East of Kailash, where she and her husband host a large Christmas lunch gathering every year.

Massey says the jalebis from the famous Chandni Chowk Jalebiwala were an essential element of her Christmas celebrations. “The Jama Masjid area played a very important role in the Christmas feast,” she says, as the kababs and biryani would come from there. A large Christmas Mela would follow at her church till New Year. Food in the mela would also come from the Jama Masjid area.

The only western element in the largely Mughlai food affair are the Christmas cakes, which are prepared at every Christian home months ahead, and made at special bakeries in Old Delhi. “Even now we get our cakes made from the Old Delhi bakeries,” says Jacob.

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Thousands of people, regardless of religion, from the Old Delhi quarters of Dariba Kalan, Chhipiwada, Gali Guliyan, would flock to the church on the day of Christmas and for the Christmas mela, says Massey. “Many would go ‘church hopping’ at night, much the same way people go pandal hopping during Durga Puja,” she says.

Many of the Christian families from Old Delhi have now moved to other parts of the city, carrying with them much of the spirit and traditions from the walled city. Jacob, like every year, is busy preparing the Christmas lunch at her home. She is expecting over a hundred people this year. “The number is a lot more on most years,” she says, adding that almost no one in her guest list is a Christian, since most Christian families host their own feasts.

The menu for the party includes delicacies such as biriyani, aloo gosht, nihari, korma, paaye, and kababs, accompanied by a few vegetarian items. “All my vegetarian food is cooked by the halwais of Sitaram Bazar in Old Delhi. The non-vegetarian dishes are made by the bawarchis from Jama Masjid area and our kabab walas come from Shahjahanpur in Uttar Pradesh,” she says. This she says is the spirit of India, where Christmas food from Sitaram Bazar and Jama Masjid is laid out at a home of a Christian, for guests who are all non-Christians.

Eid-e-Tawallud translates as the celebration of the birth of Jesus (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

Eid-e-Tawallud translates as the celebration of the birth of Jesus (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury) Juliana Dias Da Costa was allotted a piece of land to build a sarai (traveller’s inn) of her own, in the area that we today know as Sarai Julena in New Friends Colony. (Express Photo by Amit Mehra)

Juliana Dias Da Costa was allotted a piece of land to build a sarai (traveller’s inn) of her own, in the area that we today know as Sarai Julena in New Friends Colony. (Express Photo by Amit Mehra) The Holy Trinity Church next to Turkman Gate (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

The Holy Trinity Church next to Turkman Gate (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury) The St. James’ Church at Kashmere Gate (Wikimedia Commons)

The St. James’ Church at Kashmere Gate (Wikimedia Commons) Illuminated view of Central Baptist Church at Chandni chowk on the Eve of Christmas Day. (Express Photo by Praveen Khanna)

Illuminated view of Central Baptist Church at Chandni chowk on the Eve of Christmas Day. (Express Photo by Praveen Khanna) Inscription in Urdu inside the Holy Trinity Church (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)

Inscription in Urdu inside the Holy Trinity Church (Express photo by Adrija Roychowdhury)