The Indian Councils Act of 1861 reconstructed the Governor-General’s Council and separated the legislature from the executive. This was followed by a series of reforms in 1891 and 1909 which sought to increase the representation of Indians within the various councils of the government.

Then there were the constitutional experiments carried out by Indians themselves. Historian Rohit De in his chapter, ‘Constitutional Antecedents’ in the book, ‘The Oxford Handbook of the Indian Constitution’ writes that the most articulate statement of liberal constitutionalism came from Raja Ram Mohan Roy in early 19th century Calcutta. De explains that Roy in his early tracts was vociferous in his defence of the freedom of press and spoke out against the invasion of civil rights of Indians such as their exclusion from juries.

There was also Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s Swaraj Bill of 1895 which is often cited as being the first non-official attempt at drafting a Constitution for India. The document provided for a small list of broadly worded rights such as the right to free speech and expression, property, personal liberty, equality before law, equality of right to admission to public offices and the right to petition for grievances.

But it is only from the 1920s that we see the popularisation of Indian constitutional law. The 1919 Montague-Chelmsford reforms was the genesis of responsible government in India. It expanded the participation of Indians in the governments. In 1928, the All Parties Conference convened a committee in Lucknow to prepare a Constitution of India. It was chaired by Motilal Nehru and the document was then known as the Nehru Report. After its submission in 1929, the Congress declared complete Independence as its goal and declared that the Constitution of India would be written by Indians themselves through an elected Constituent Assembly.

B R Ambedkar, one of the drafters of India’s Constitution (Express archive photo)

B R Ambedkar, one of the drafters of India’s Constitution (Express archive photo)

The next big landmark moment in the process of making the Indian Constitution was the 1934 Government of India Act enacted by the British Parliament. The Act is considered to have been the longest piece of legislation enacted by the British Parliament at the time. Some of its most crucial features included the creation of a federation of India with a central executive and Parliament on top and the provinces and princely states below it, separate electorates for Muslims and Sikhs, and critical emergency powers to be enjoyed by the Governor.

Story continues below this ad

The Act was heavily criticised by the Congress and the Muslim League. While Nehru called it a ‘Charter of Slavery’, Mohammad Ali Jinnah thought it to be “thoroughly rotten, fundamentally bad and totally unacceptable.” It is only in 1942 that the British government conceded to the request of Indians to frame their own Constitution through a Constituent Assembly.

In 1945, the Labour Government in England announced its plan to create a Constituent Assembly of India to be elected indirectly by the Provincial Assemblies. Elections to 296 seats from the British Indian provinces were completed by July-August 1946, while 93 seats for the princely states remained vacant since they refused to be a part of the Assembly till well into 1947. The work of the Assembly was further complicated by the fact that Jinnah withdrew his acceptance and caused the Muslim League to boycott it, thereby making the Partition of India inevitable.

The Congress, however, went ahead with its plans and the Assembly opened in December in the Constitution Hall. Four days later, Nehru moved the historic Objectives Resolution in the Assembly which formed the guiding principles and philosophy of writing the Constitution.

The making of Pakistan’s Constitution

By January 1947, when it became clear that there was no hope for the Muslim League to join the Constituent Assembly, the Governor-General of the time, Lord Mountbatten, announced the setting up of a separate Assembly for Pakistan. Since its inception, Pakistan has been plagued by questions surrounding the Islamic character of the state, and the issue of federalism, compounded by the geographic divisions between West and East Pakistan.

Story continues below this ad

Those questions would complicate the country’s constitutional process, resulting in multiple iterations and amendments, most notably in 1954, 1956 and finally, in 1973, after the separation of East Pakistan and subsequent formation of Bangladesh.

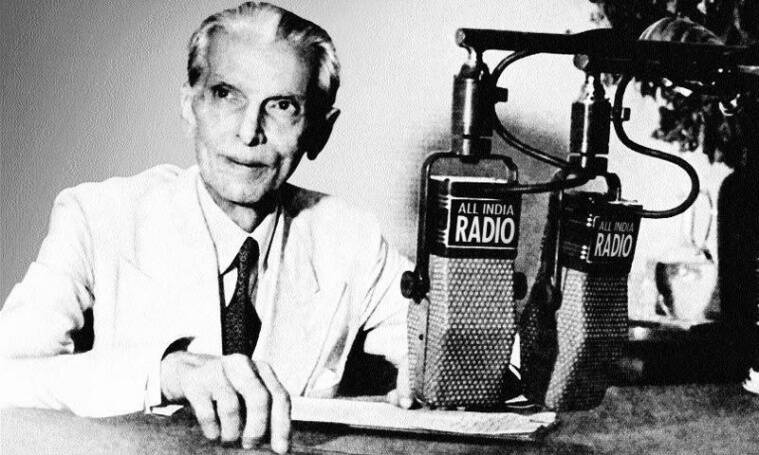

From the beginning, Pakistan’s national identity was the subject of much focus. In a radio talk broadcast in 1948, Jinnah expressed his desire for the Constitution to “be of a democratic type, embodying the essential principles of Islam.” However, Jinnah represented the moderate faction of Pakistani lawmakers and his death, only a few months after the broadcast, greatly complicated issues.

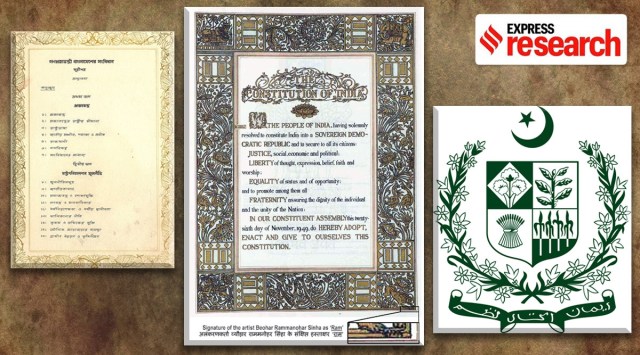

Jinnah announcing the creation of Pakistan over All India Radio on 3 June 1947. (Wikimedia Commons)

Jinnah announcing the creation of Pakistan over All India Radio on 3 June 1947. (Wikimedia Commons)

Years before the first Constitution was to be formalised, Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly passed the Objectives Resolution to define the basic directives of the state. In an article for the Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World, the author Rizwan Hussain writes that the Objectives Resolution reflected a “compromise between traditionalists and modernists,” with the former achieving its goal of forming an Islamic Republic and the latter, in securing basic freedoms under democratic principles.

Towards that end, the resolution states that “the principles of democracy, freedom, equality, tolerance and social justice, as enunciated by Islam shall be fully observed,” and that “the Muslims shall be enabled to order their lives in the individual and collective spheres in accord with the teaching and requirements of Islam as set out in the Holy Qurʿan and Sunna.”

Story continues below this ad

From the beginning, the resolution proved to be extremely controversial. Large numbers of non-Muslim members of government, especially from East Pakistan, argued that the Objectives Resolution differed with Jinnah’s (Quaid-e-Azam) views. One member, Chandra Chattopadhyaya, said, “what I hear in this Resolution is not the voice of the great creator of Pakistan – the Quaid-i-Azam, nor even that of the Prime Minister of Pakistan the Honourable Mr. Liaquat Ali Khan, but of the Ulema of the land.”

Nevertheless, the Objectives Resolution has served as the preamble for all three of Pakistan’s constitutions, the first of which took three Governors-General, four Prime Ministers, two Constituent Assemblies, and nine years to enact.

The first Constitution of Pakistan was enacted in 1956 amidst much opposition by Hindu majority parties and the largest Muslim political party in East Pakistan — Awami League — rejecting it. Their biggest concern was the distribution of power, with both arguing that the document favoured West Pakistan, and particularly the state of Punjab.

An important development leading up to the passage of the Constitution was the decision to amalgamate all the states of West Pakistan into one unified territory, an act known as the One Unit Scheme of 1955. One Unit was designed to overcome the difficulty of administering the two unequal states of West and East Pakistan which were separated from each other by more than one thousand miles. However, in Politics of Identity, historian Adeel Khan maintains that the scheme was viewed as a counterbalance against the political and population dominance of the ethnic Bengali population of East Pakistan.

Story continues below this ad

Despite the province of East Pakistan accounting for a clear majority of the total population, its representation in the National Assembly was set at half the total membership, fuelling discord between citizens of East and West.

In Politics of Nationalism, University of Westminster Professor, Gulawar Khan writes that Punjab, which dominated the military and bureaucracy during the colonial period, did not want to lose its supremacy in Pakistan under the majority of Bengal. Maintaining its control would only be possible with the merger of smaller provinces into one large province dominated by Punjab. Thus, even the smaller states of Pakistan opposed the scheme.

These concerns over power imbalances would ultimately doom the 1956 Constitution, and eventually facilitate the formation of Bangladesh.

A turbulent constitutional history

Only two years after the first Constitution was passed, Pakistan suffered its first military coup in October 1958 under the then general Ayub Khan. Upon seizing power, Khan appointed a Commission to fundamentally alter the Constitution, changing Pakistan from a parliamentary to a presidential system against the recommendations of his Chief Justice Muhhamad Shahabuddin.

Story continues below this ad

Under this new system, the President of Pakistan, Khan, was allotted significantly more power, further isolating the political participation of East Pakistanis. After years of unrest, in 1966, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, also known as Mujib, announced his six-point plan for East Pakistan provincial autonomy, at a conference of both the eastern and western chapters of the Awami League in Lahore. Mujib, the General Secretary of the All Pakistan Awami League, had long championed for the rights of East Pakistanis and vehemently opposed the leadership of Khan.

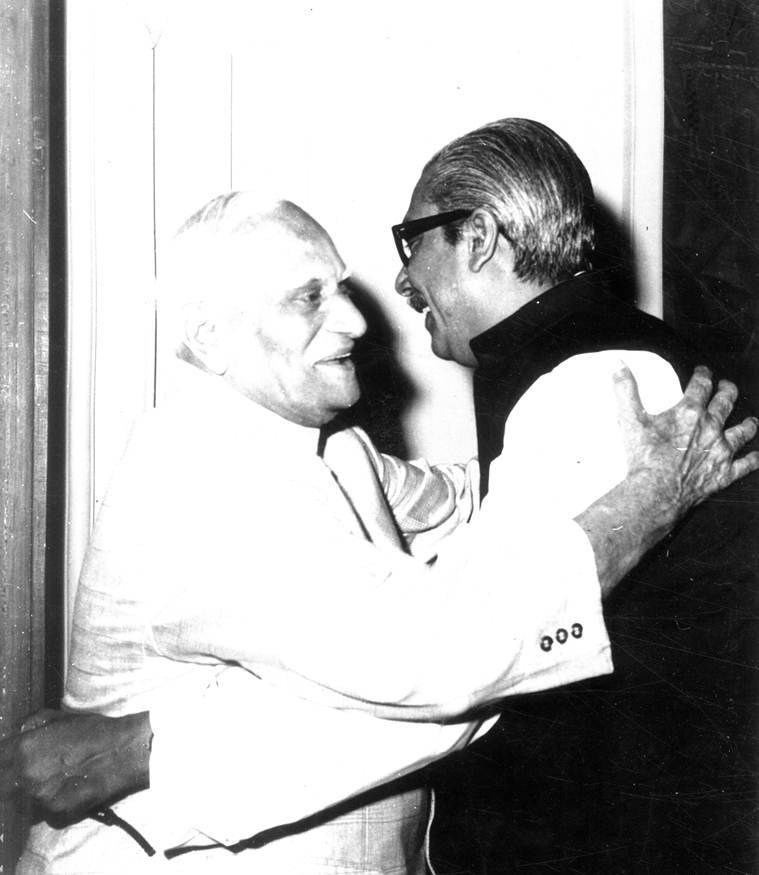

Indian President VV Giri receiving Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Prime Minister of Bangladesh at Rashtrapati Bhavan on May 14, 1974 (Express archive photo)

Indian President VV Giri receiving Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Prime Minister of Bangladesh at Rashtrapati Bhavan on May 14, 1974 (Express archive photo)

At the conference, he demanded, amongst other things, that the government be federal and parliamentary in nature, and its members be elected on the basis of numerical representation. Mujib’s six points were in direct opposition to Khan’s plans for greater national integration and subsequently sparked a series of protests in both wings of the country.

After months of political unrest and declining health, Khan resigned in 1968, handing over the administration of the country to General Yahya Khan who imposed a state of martial law. Yahya said that he would transition the country to democracy and promised to hold direct elections to facilitate the same. After holding talks with East Pakistan’s Governor, Yahya instituted the Legal Framework Order (LFO) in 1970, with the aim of securing a future constitution.

In Pakistan: A Modern History, Ian Talbot argues that Yahya’s plan immediate stoked fears in West Pakistan, adding that with the promise of elections “the western wing’s nightmare scenario materialised: either a constitutional deadlock, or the imposition in the whole of the country of the Bengalis’ longstanding commitment to unfettered democracy and provincial autonomy.”

Story continues below this ad

The LFO called for direct elections, and, separating from the Constitution of 1956, deemed that the National Assembly comprised 196 seats for the more populous East Pakistan, against 144 seats for the West. The LFO also dissolved the vastly unpopular One Unit scheme and stipulated that the National Assembly would have to create a new Constitution within 120 days of being convened.

However, in drafting the LFO, Yahya had made one significant miscalculation. He had assumed that the newly elected National Assembly would preserve some semblance of power for West Pakistan while satisfying the demands of its Eastern counterpart. In a drastic rebuke of Pakistani integration, the pro-separatist Awami League won all but two of the 162 seats allotted to East Pakistan, with West Pakistan’s seats divided among different political parties.

This in turn guaranteed the Awami league control of the government with Mujib as its Prime Minister. As the LFO had not specified any rules for the process of writing a constitution, the Awami League would oversee the passage of a new Constitution with a simple majority.

However, the National Assembly would never end up meeting as in West Pakistan, the Pakistan People’s Party of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto declared that it would boycott the new legislature. That decision provoked outright rebellion in East Pakistan and consequently led to the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

Story continues below this ad

Independent countries

After the succession of Bangladesh in 1971, the political landscape of Pakistan was altered significantly. Despite that, members of the Constituent Assembly that would draft Pakistan’s latest Constitution were elected in 1970 when the country was still united. As a result, the 1973 Constitution failed to resolve the conflict between two antithetical versions of identity between the Centre and the states.

The 1973 Constitution was not supported by two of the then-four provinces of Pakistan, namely the North West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) and Balochistan. Chief amongst the concerns of the two provinces was that Punjab would dominate federal politics as it constituted more than 60 per cent of the country’s population. These divisions between the Centre and the states would continue to dominate Pakistani politics with the current Constitution having been suspended twice by military coups between 1985 and 2002.

As for Bangladesh, the process of outlining a Constitution was slightly simpler. The Provisional Government of Bangladesh issued the Proclamation of Independence on April 10, 1971, which would serve as the interim first Constitution of the country. Declaring “equality, human dignity and social justice,” as the fundamental principles of the republic, the interim Constitution was formally adopted by the Constituent Assembly in November 1972.

However, the simplicity of adopting the constitution did not extend to preserving it. Although Bangladesh’s Constitution of 1972 specifies a parliamentary form of government under a prime minister, its implementation has been interrupted by a series of military coups between 1975 and 1991 when the parliamentary system was finally restored.

B R Ambedkar, one of the drafters of India’s Constitution (Express archive photo)

B R Ambedkar, one of the drafters of India’s Constitution (Express archive photo) Jinnah announcing the creation of Pakistan over All India Radio on 3 June 1947. (Wikimedia Commons)

Jinnah announcing the creation of Pakistan over All India Radio on 3 June 1947. (Wikimedia Commons) Indian President VV Giri receiving Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Prime Minister of Bangladesh at Rashtrapati Bhavan on May 14, 1974 (Express archive photo)

Indian President VV Giri receiving Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Prime Minister of Bangladesh at Rashtrapati Bhavan on May 14, 1974 (Express archive photo)