In 1939, at the height of the freedom struggle, a group in Bombay sought to put up a statue of Mahatma Gandhi. On learning about it, Gandhi is reported to have been livid and later wrote in the Harijan, “It will be a waste of good money to spend ₹25,000 on erecting a clay or metallic statue of the figure of a man who is himself made of clay…”

That this was one matter where Gandhi didn’t have his way is evident from the Mahatma statues that are everywhere, all these years later – from government buildings, maidans, street corners and neighbourhoods in India to those in cities abroad.

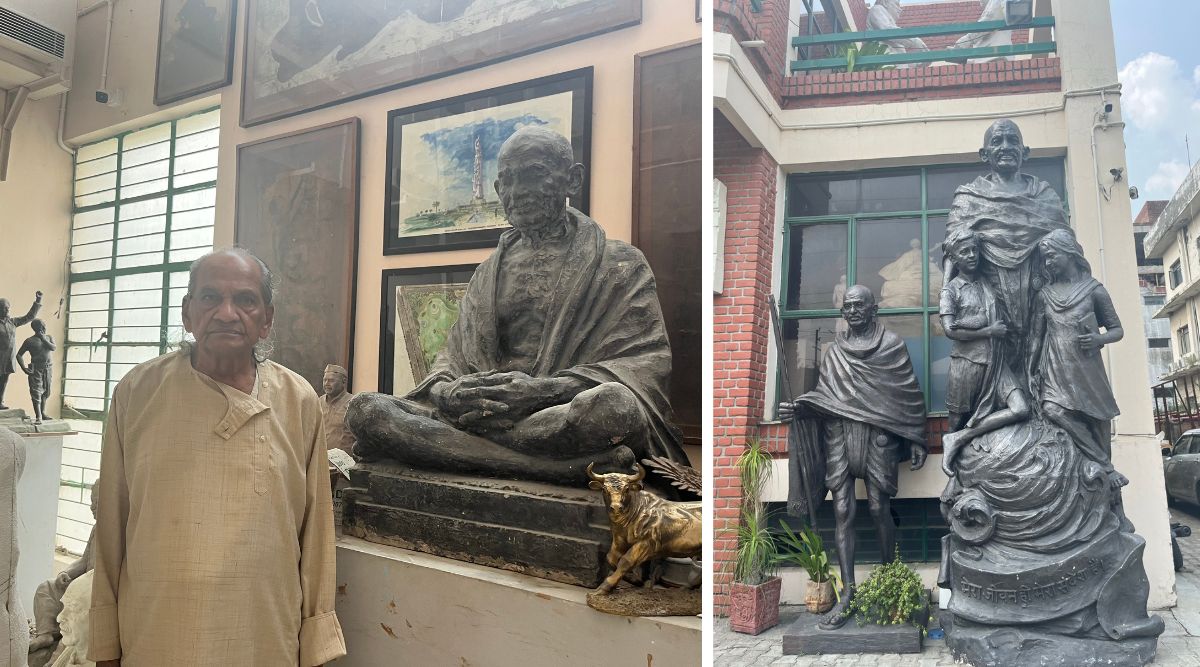

Ram Sutar, 98, the sculptor most famous for creating Gandhi’s statues, proudly claims that his recreation of Gandhi is “present in 450 cities”.

The Gandhi Vatika in New Delhi. (Adrija Roychowdhury)

The Gandhi Vatika in New Delhi. (Adrija Roychowdhury)

Ahead of the recent G20 Summit, President Droupadi Murmu inaugurated a 12-foot statue of the Mahatma right across Raj Ghat in New Delhi. Surrounded by about five other Gandhi statues, the statue is skirted by big bold letters proclaiming “I (heart) Gandhi Darshan G20”. The Gandhi Vatika, as the small complex of statues is called, is perhaps the most recent in the long history of both national and international commemoration of Gandhi in stone.

More often than not, in many of these statues, the Mahatma is imagined in two iconic postures: seated in a meditative pose or standing with a staff in hand.

Recreating the Mahatma in India

It was after the Mahatma’s death, though, that the practice of making his statues picked up.

New Delhi’s Gandhi Vatika comprises multiple statues of Gandhi. (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury)

New Delhi’s Gandhi Vatika comprises multiple statues of Gandhi. (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury)

Sutar narrates how he made a sculpture of Gandhi for the first time in 1948, soon after the news of his death broke. Sutar, then studying in Dhule, Maharashtra, was asked by one of his teachers, a devout follower of Gandhi, to make a sculpture of the Mahatma. Himself a Gandhi devotee since the 1930s, when he participated in the Swadeshi campaign in Dhule, Sutar was overjoyed. He immediately sculpted a 4-foot bust of Gandhi, copying from one of his photographs. The bust was kept at his school and he gifted two copies of the same to schools in nearby villages.

Story continues below this ad

Sculptor Ram Sutar’s (left) statues of Gandhi are “present in 450 cities”. A statue of Gandhi by Ram Sutar (right). (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury)

Sculptor Ram Sutar’s (left) statues of Gandhi are “present in 450 cities”. A statue of Gandhi by Ram Sutar (right). (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury)

Through the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, statues of colonial officials commissioned by the British, created in studios and foundries in England, had started being replaced by statues of local freedom fighters being made by the first group of Indian sculptors.

Historian Tapati Guha-Thakurta has, in her article “Why Statues Matter”, pointed to the unique challenges the early local sculptors found themselves in as they replaced those who had been trained in sophisticated European fine arts.

Guha-Thakurta notes how in the 1930s and 1940s, Debi Prosad Roy Chowdhury “can be seen to step in and take over, here, a practice that was still largely a monopoly of Western sculptors”, as he created bronze sculptures of Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee and Surendranath Banerjee in Calcutta.

It was Roy Chowdhury’s bronze sculpture of Gandhi on his Dandi March in Calcutta that really shot him to fame.

Story continues below this ad

Interestingly, Roy Chowdhury managed to complete the statue in 1958, only after taking recourse to melting a bronze bust he had made of his own father — to meet an acute shortage of metal in Calcutta that year — to replace the leg of his Gandhi statue that had been damaged while being lifted to the pedestal.

The ‘Dandi March’ by sculptor Ram Sutar. (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury)

The ‘Dandi March’ by sculptor Ram Sutar. (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury)

“We are invited to think here of an affective flow of molten bronze from the figure of Debiprosad’s own father to that of the ‘father of the nation’,” writes Guha-Thakurta. The statue stood at the Park Street-Chowringhee junction in Calcutta till the 1980s, when it was removed to the Red Road junction.

The placement of Gandhi in the National capital was, of course, of monumental concern to the Central government. Sutar narrates how he was commissioned to create a sculpture of Bapu to replace the one of George V that stood under a canopy at India Gate sometime in the 1960s.

“I first thought of creating Gandhi on the lines of his philosophy of asprushyata nivaran (eradication of untouchability),” says Sutar.

Story continues below this ad

Accordingly, his idea was to sculpt Gandhi with his hands placed on the heads of two children surrounding him. Sutar also created another model of a seated Gandhi in a meditative pose. It was the latter that came to be selected for the canopy.

However, the statue never made its way under the canopy. In response to huge opposition from parliamentarians and Gandhians against the idea of placing the Mahatma under a canopy meant for the King of Britain, it was decided to place it at Parliament in 1993. In the years to come, the 16-foot Gandhi statue became an iconic space of protests by parliamentarians.

“It remains one of my most favourite sculptures of Gandhi because it truly is a message to the country about his importance as the father of the nation,” says art critic and curator Gayatri Sinha. More recently, the statue was removed once again and is, at present, placed in the right corner of the new Parliament, facing the old building.

Sutar’s other statue of Gandhi with the children made its way to Patna’s Gandhi Maidan, where it was inaugurated in 2013 by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar. Made at a cost of Rs 35 crore, the 72-foot statue is believed to be the tallest Gandhi statue in the world.

Story continues below this ad

Sinha says, “In most statues of Gandhi, the attitudes are of silence, meditativeness and a certain inner energy. The other comparable figure is that of the Buddha, which has a similar image.”

The statue of the Mahatma at Gandhi Ashram in Sabarmati, Gujarat. (Express Photo by Nandagopal Rajan)

The statue of the Mahatma at Gandhi Ashram in Sabarmati, Gujarat. (Express Photo by Nandagopal Rajan)

These large state-sponsored statues of Gandhi aside, in the villages and smaller towns of India, statues of Gandhi tend to take on a whole new avatar. As historian and author of Gandhi in the Gallery: The Art of Disobedience Sumathi Ramaswamy explains, many of them are rather crude or humble with variations in iconography that one will not find in large public statues present in the big cities.

“One of my favourite examples is a photograph of a Gandhi statue located in Rajahmundry in Andhra Pradesh that I came across in (photographer) Raghu Rai’s book. It depicts Gandhi being protected by a cobra over his head, which is a typical Vaishnav iconographic depiction,” Ramaswamy says.

Very often, these humble Gandhi statues in the countryside do not even carry the names of their sculptors. “But they do tell us a lot about the nature of Indian democracy, where so many different communities assert their identities through Gandhi,” Ramaswamy adds.

Gifting the Mahatma

Story continues below this ad

Apart from being a local and national symbol, Gandhi is just as much a global icon. The evidence of his global appeal perhaps lies in his statues dotting hundreds of cities across the world.

In early 1950, Hindu monk Paramahansa Yogananda created the Gandhi World Peace Memorial at Lake Shrine, California, where a portion of the Mahatma’s ashes are kept. Although not a statue, it marked the beginning of the long list of monuments dedicated to Gandhi that came up globally in the following years.

The statue of Gandhi at Parliament Square in London. (Photo source: Wikipedia)

The statue of Gandhi at Parliament Square in London. (Photo source: Wikipedia)

In 1968, the British Prime Minister unveiled a bronze statue of Gandhi, created by Polish sculptor Fredda Brilliant, at Tavistock Square in London to mark the centenary celebrations of the Mahatma’s birth. In 1993, a statue of Gandhi was unveiled at Pietermaritzburg, a province of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, to mark the centenary since Bapu was thrown off a train at Pietermaritzburg railway station.

In 2015, the British government installed another statue of Gandhi at Parliament Square in Westminster, London. It is indeed ironic that while announcing the installation of this statue, the UK High Commissioner to India had said that “it will mark the recognition by Britain that Gandhi was an honoured part of our history too, as well as India’s.”

Story continues below this ad

It is worthwhile to note that despite the large pantheon of nationalist leaders that India boasts of, it is only the statue of Gandhi that has, time and again, been the object of state gifts to nations including Finland, the United States, Malawi, Argentina and Australia.

“Gandhi is the most recognised Indian in the world. He is also identified with values such as peace and tolerance that India would like to project regardless of political realities on the ground,” explains Ramaswamy.

A comparison can be drawn with the statues of Bhagat Singh, that one is most likely to come across in Punjab. Historian Chris Moffat, who has written a book on the commemorative politics of Bhagat Singh, says that many of the large-scale statues dedicated to the revolutionary freedom fighter in Punjab were sponsored by the Congress in the 1980s “to appeal to Punjabi regional identities as part of a broader national project”. However, Moffat says, one hardly comes across a statue of Bhagat Singh in countries like Canada and the UK, which have a significant Punjabi diaspora population.

The statue of Gandhi in San Francisco. (Express Photo by Nandagopal Rajan)

The statue of Gandhi in San Francisco. (Express Photo by Nandagopal Rajan)

Political scientist Simona Vittorini has argued that the act of gifting Gandhi statues is part of India’s “soft power strategy”. In a 2021 article, Vittorini takes the case of a Gandhi statue gifted by former President Pranab Mukherjee to the University of Ghana in Legon, Accra, in 2016. She notes that even though historically India’s presence in Ghana goes back a long way, “it was the friendship between India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Ghana’s first post-independence leader Kwame Nkrumah that cemented the relations between the two countries”.

Story continues below this ad

“So why gift a statue of Gandhi and not one of Nehru?” she asks.

However, the statue had to be removed from the campus on account of severe opposition from a section of lecturers and students, who pointed to “racist remarks” made by Gandhi on Black South Africans and called the gift a “slap in the face that undermined Ghana’s struggle for autonomy, recognition and respect”.

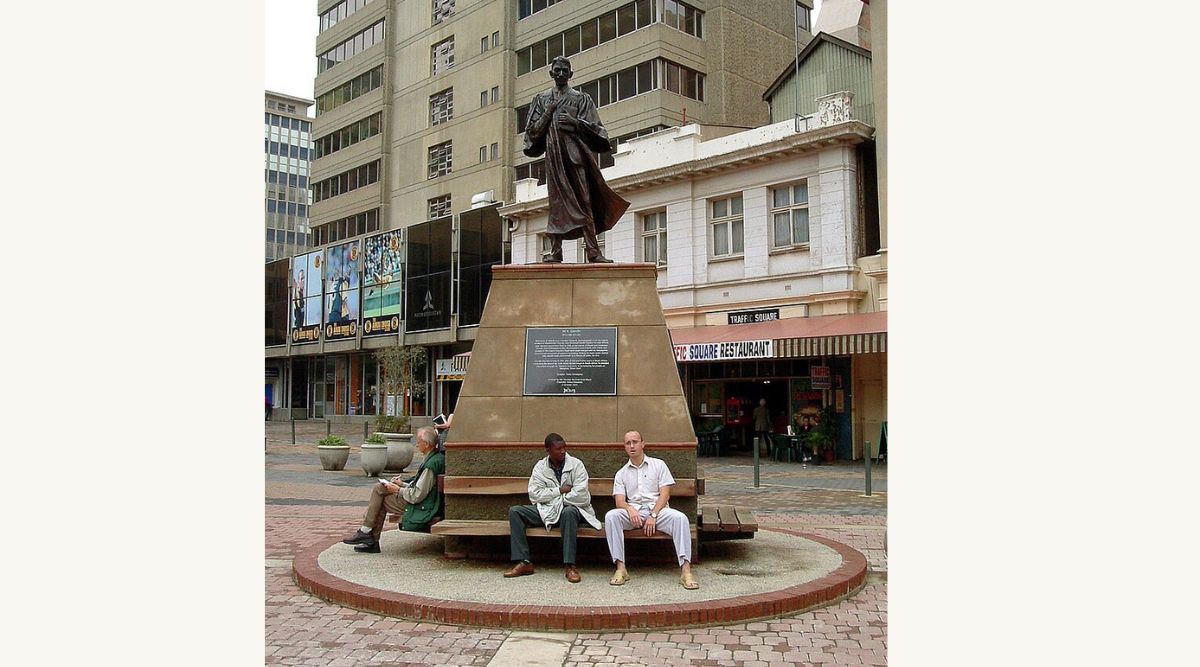

Ramaswamy points out that apart from the Indian state, its diaspora too has found value in gifting Gandhi statues to assert their identity abroad. One of her favourite Mahatma statues is located at Gandhi Square in Johannesburg, she says. Sculpted by Tinka Christopher, it was created with funds raised locally. Unlike other statues of Gandhi, it depicts him as a young man wearing a barrister’s gown over his suit and holding a book in hand.

Tinka Christopher’s statue of the Mahatma at Gandhi Square in Johannesburg. (Photo source: Wikipedia)

Tinka Christopher’s statue of the Mahatma at Gandhi Square in Johannesburg. (Photo source: Wikipedia)

Vandalising the Mahatma

In recent years though, Gandhi has also come to be seen through a more critical lens. It has resulted in recent cases of vandalism of his statues in many parts of the world. Every time an act of vandalism of a statue of Gandhi comes into public knowledge, the Indian government is forced to put out a statement condemning the same.

In some of these cases, the attack on his statue reveals aspects of Gandhi’s life and past views that were largely ignored until recently.. “In the US, the UK and Europe, the language of the attack is on Gandhi’s racism, casteism and increasingly on his sexual behaviour,” says Ramaswamy.

In case of the petition for the removal of the statue in the University of Ghana though, the language of critique would appear to be a pushback against the Indian state. “It is better to stand up for our dignity than to kowtow to the wishes of a burgeoning Eurasian super-power,” said the petition.

The Separatist movements in the diaspora and protests within India too have found echoes in acts of vandalism against the statues of Gandhi abroad. In 2020, for instance, a peaceful protest in front of the Indian Embassy in Washington DC against farm laws was disrupted by supporters of the Khalistan movement, who ended up vandalising the statue of Gandhi located there. Slogans in support of Khalistan have been smeared across statues in Toronto and Milan, among others.

“Given that the Khalistan movement did not even exist during Gandhi’s lifetime, it is quite fascinating that the Khalistan leaders abroad have turned to the Gandhi statue to push back against India,” says Ramaswamy.

Meanwhile, within India, the statues of Gandhi are beginning to find new companions. The statues of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Subhas Chandra Bose have, of course, made huge headlines. Statues of BR Ambedkar too have been in proliferation across the country. At Sutar’s studio in Noida, where his workmen are busy sculpting hundreds of statues, the 98-year-old says he is not working on any statue of Gandhi at present. Prominent among the statues being made in his studio currently are those of Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj, Ambedkar, Nadaprabhu Kempegowda as well as Lord Shiva.

The Gandhi Vatika in New Delhi. (Adrija Roychowdhury)

The Gandhi Vatika in New Delhi. (Adrija Roychowdhury) New Delhi’s Gandhi Vatika comprises multiple statues of Gandhi. (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury)

New Delhi’s Gandhi Vatika comprises multiple statues of Gandhi. (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury) Sculptor Ram Sutar’s (left) statues of Gandhi are “present in 450 cities”. A statue of Gandhi by Ram Sutar (right). (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury)

Sculptor Ram Sutar’s (left) statues of Gandhi are “present in 450 cities”. A statue of Gandhi by Ram Sutar (right). (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury) The ‘Dandi March’ by sculptor Ram Sutar. (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury)

The ‘Dandi March’ by sculptor Ram Sutar. (Express photos by Adrija Roychowdhury) The statue of the Mahatma at Gandhi Ashram in Sabarmati, Gujarat. (Express Photo by Nandagopal Rajan)

The statue of the Mahatma at Gandhi Ashram in Sabarmati, Gujarat. (Express Photo by Nandagopal Rajan) The statue of Gandhi at Parliament Square in London. (Photo source: Wikipedia)

The statue of Gandhi at Parliament Square in London. (Photo source: Wikipedia) The statue of Gandhi in San Francisco. (Express Photo by Nandagopal Rajan)

The statue of Gandhi in San Francisco. (Express Photo by Nandagopal Rajan) Tinka Christopher’s statue of the Mahatma at Gandhi Square in Johannesburg. (Photo source: Wikipedia)

Tinka Christopher’s statue of the Mahatma at Gandhi Square in Johannesburg. (Photo source: Wikipedia)